Day out: a tour of cholera in London

Published in Microbiology

Day out: a tour of cholera in London

Recently, I had a friend from my postdoc lab come visit me in London. We had both worked on Vibrio cholerae (the bacterium that causes the diarrhoeal disease cholera), and in celebration of London’s role in the discovery of how cholera is transmitted (and frankly, a fair amount of desperate brainstorming about how to entertain a microbiologist), we set out to sightsee the history of cholera in London on a sunny, wintry Saturday.

The first stop is the River Thames, which today is a real destination, offering a pleasant winding walk that takes you to the major sites of the city: Parliament, the London Eye, the Globe Theatre and the Tate Modern.

- View along the Thames: Parliament (center) and London Eye (left).

But now imagine yourself back to 1855 when the Thames was an open sewer, accumulating all the human, animal and industrial waste of the region. In that year, Sir Michael Farraday conducted an experiment where he measured the depth at which white paper when dropped into the Thames consistently disappeared from view. The answer: an inch upon sinking. He subsequently wrote to the Times, noting that “near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface even in water of this kind.” Suffice to say, people hated being around the river, while Vibrio cholerae was happier than a pig in…well, the Thames.

- "The silent highwayman: Death rows on the Thames, claiming the lives of victims who have not paid to have the river cleaned up, during the Great Stink." From Punch Magazine, Volume 35 Page 137; 10 July 1858

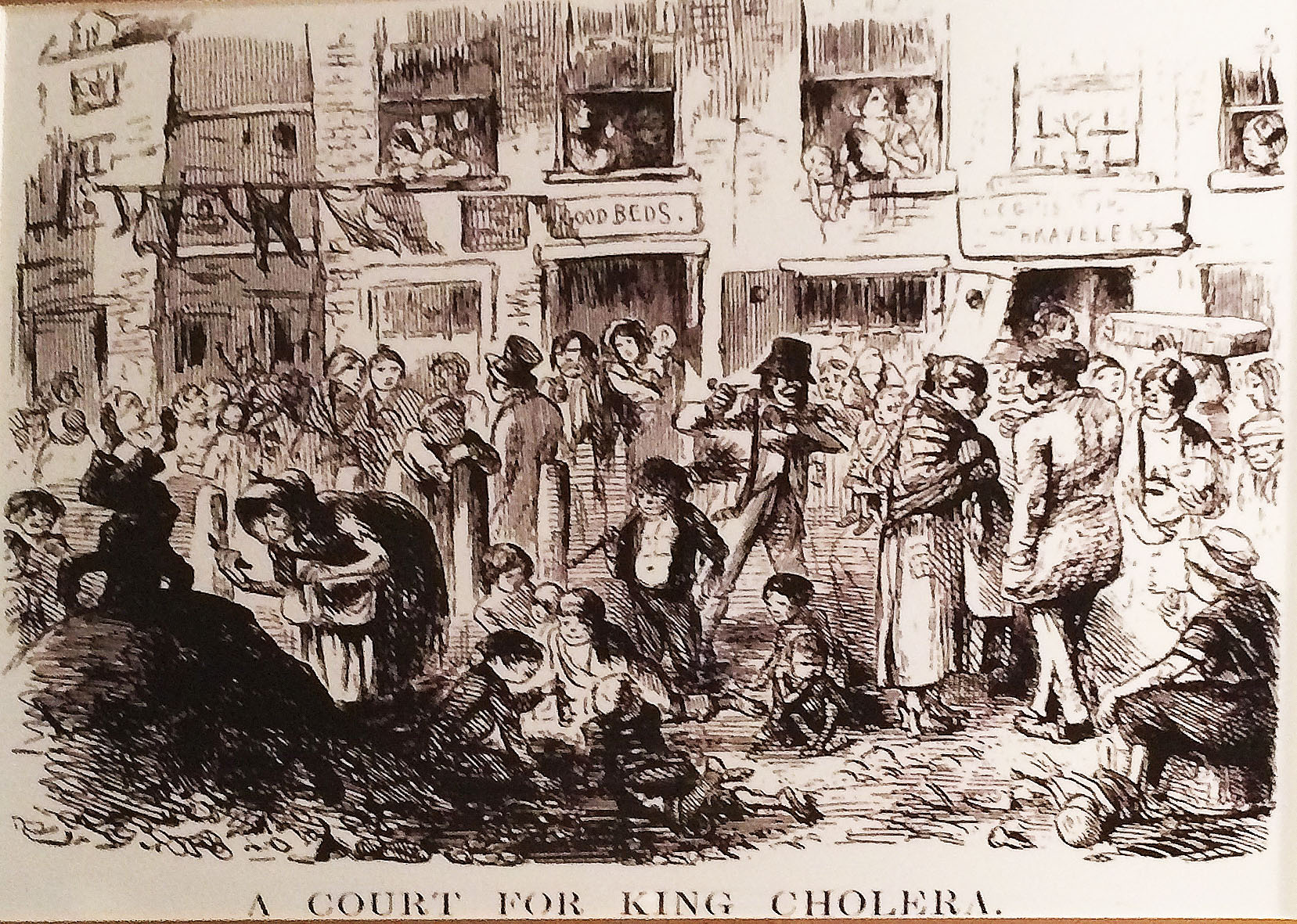

After taking in the river, we walk north into SoHo, and as you wander down the boutique-lined streets, consider that cholera epidemics were common through the 1800s in the West, having spread from the Indian subcontinent into the unsanitary urban slums. London itself had 3 major epidemics in 1831, 1848 and 1853, killing over 20,000 people. We are heading to the John Snow pub on Broadwick street, in the heart of one of the afflicted neighbuorhoods and also, as some would argue, the birthplace of modern day epidemiology.

- John Snow Pub on Broadwick Street

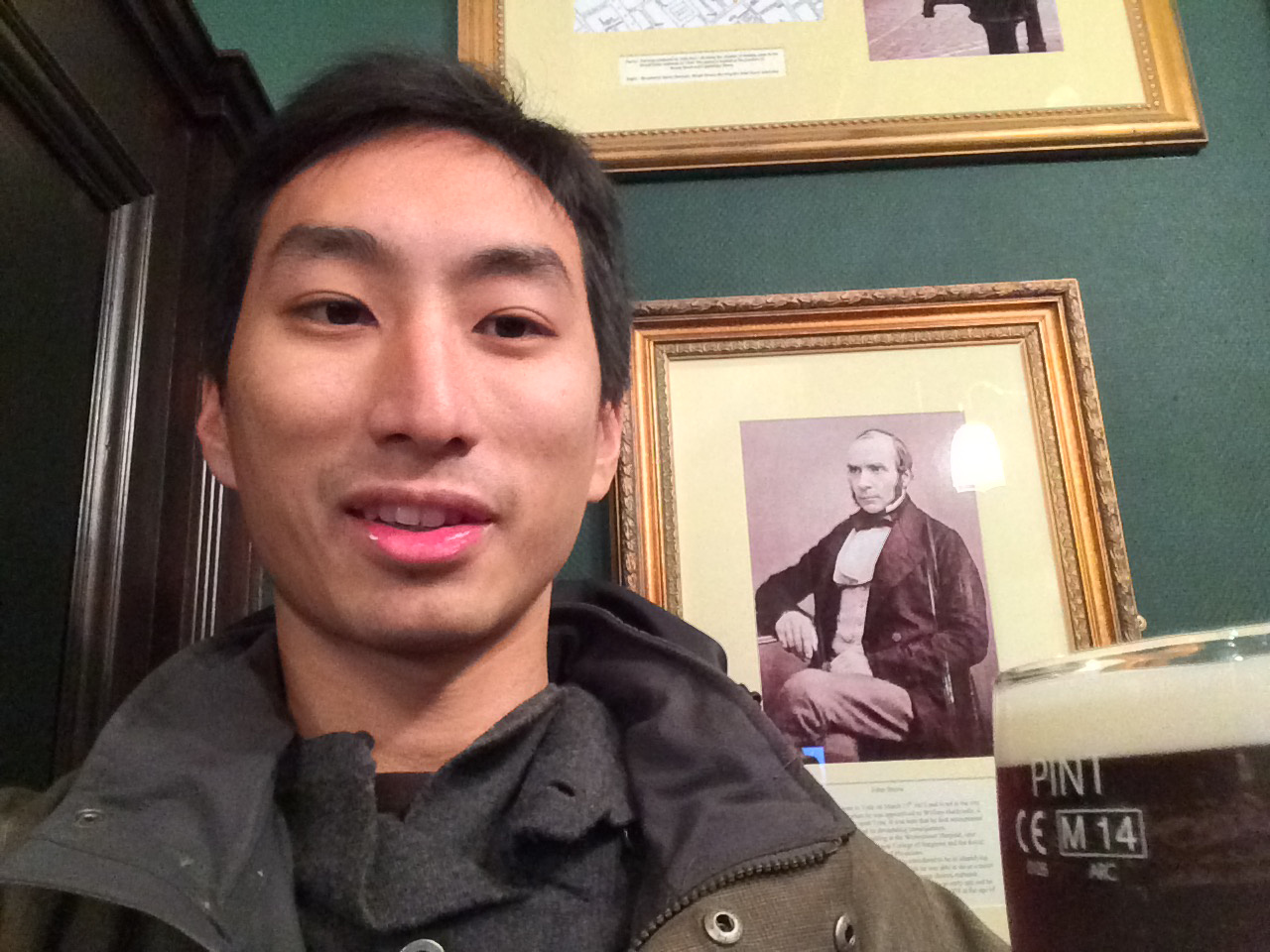

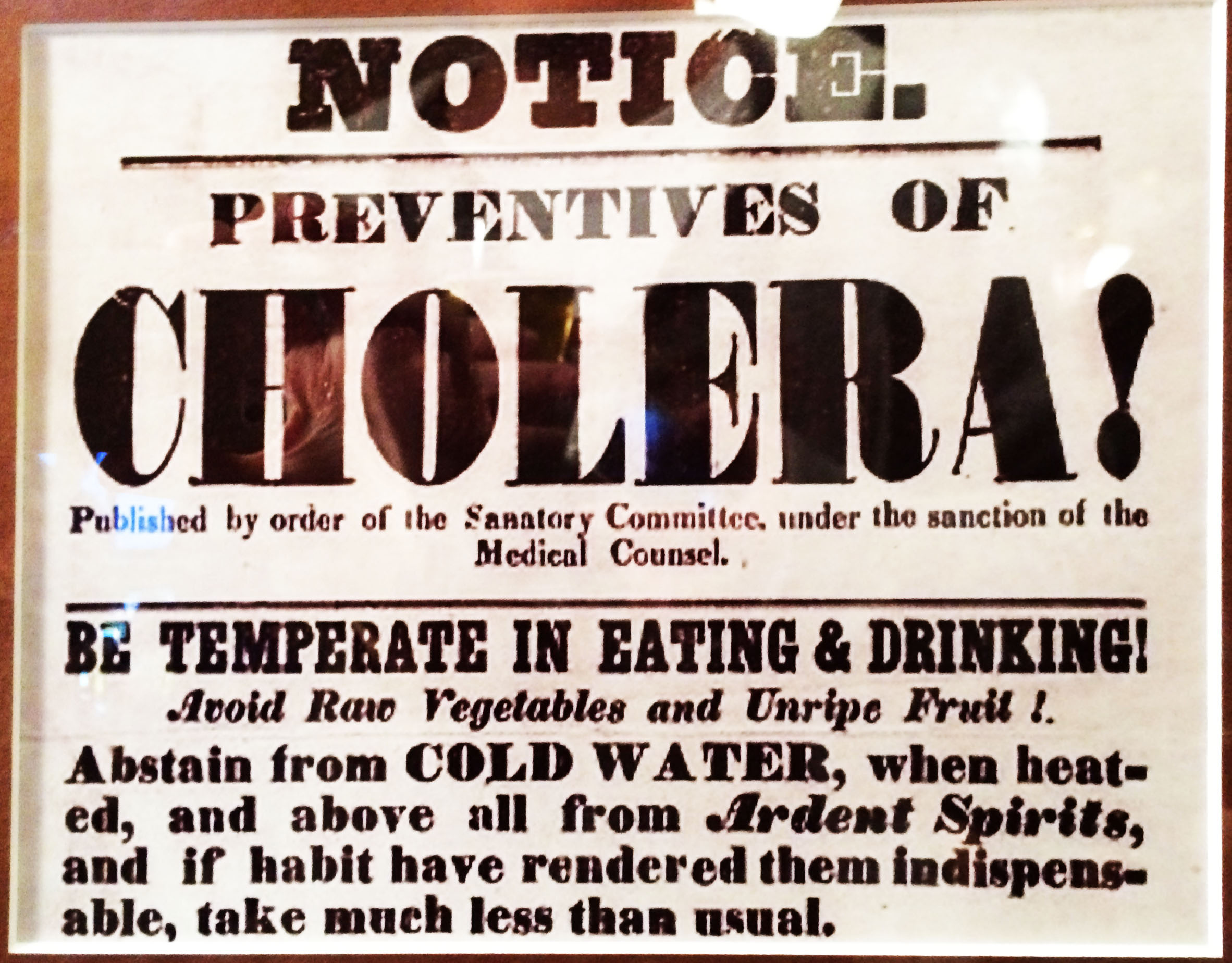

It was here that the doctor John Snow mapped the afflicted local households during the 1853 epidemic and traced the infections to a neighbourhood well that was drawing water from the river. Up to this point, people had largely believed that cholera was spread via miasma, the foul stench of decay. But through his work, Snow was able to convince the municipal government that cholera was actually waterborne. They subsequently removed the handle of the well pump and new infections in the neighbourhood ceased. The famous pump still stands, but is undergoing renovation at the moment, so drop into the old fashioned John Snow pub instead and peruse the almost fanciful cholera posters of the 1800s all along the wall. And don’t forget to toast Snow’s portrait with a pint before you leave.

- Cheers to John Snow (portrait in the background)!

After some revelry, we finish the day at the Wellcome Collection, a free museum housing an interesting (and sometimes, creepy) array of medical paraphernalia collected by the philanthropist, Henry Wellcome, of the Wellcome Trust. In the Medicine Now exhibit is an amazing piece of early microbiological research history: video from 1913 visualizing the single cell behaviours of V. cholerae. The video is all but 5 minutes, but it’s hard to imagine that without our modern tools of fluorescence microscopy, microfluidic devices and imaging software, scientists were able to reproduce—through clever changes in incubation time and culture medium—the major aspects of the Vibrio lifecycle that we still investigate today (i.e., the transition to spherical morphology during stationary phase, bacterial flagellar motility, and biofilm formation).

- Movie clip showing bacterial motility and the transition to spherical morphology during extended incubation

So there you have it: a cholera themed day out in London. A bit of history, a bit of sightseeing and some drinking. Not bad for a nerdy vacation, yes? And if you've got any other microbiology themed day trips, please post an itinerary and some pictures for all to see.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in