Detecting changes and loss of smell during COVID-19 with Large Language Models

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Computational Sciences, and General & Internal Medicine

It is thought that the most important feature of an odor is how much pleasure it causes: you like it or you don't like it. Next comes how odors bring out memories, perhaps because smell is linked to the importance of the affective dimension : An odor easily takes you back to past places, to imagine your mother or grandmother cooking, to childhood . The connection between smell and emotion is so close that the psychologist Rachel Herz has wondered "whether we would have emotions with no sense of smell; I smell, therefore I feel?" Herz's thoughts mirror those of Plato, who wondered if you could reason without vision, and somehow also to those of the German primatologist Michael Tomasello, who wondered if we would have language without vision. Summarizing the different relationships between perceptual modalities and cognitive processes, the eminent psychologist and specialist in the study of sensory perception, Trygg Engen wrote: "Functionally, smell may be to emotion what sight or hearing is to cognition." However, the most common hypothesis is that we are not good at recognizing and therefore describing smells with words, we hear over and over that language is not adapted to describe smells.

This is where artificial intelligence comes in to solve the dilemma of language adequacy to describing odors and the relationship between language and smell. In past work, with data published in 2017 by our colleagues Leslie Vosshall and Andreas Keller, we were able to build a neural network model that, based on the structure of any molecule, could predict how it would smell using 19 words. The words that we could best predict were garlic, intensity, fish, sweet, fruit, spices, smell of burning and flower. For the first time, we were able to build a model that was able to predict not only pleasure and intensity elicited by an odor, but also its semantic dimensions.

Not only that, based on these models we built we were also able to predict a more complex set of descriptors, 130 words to describe an odor. So instead of just predicting whether a molecule smelled like fruit, we could now predict whether it smelled like apple, grape, pear, orange, lemon, strawberry or pineapple; if instead of the smell of a flower it was violet, rose, daisy or magnolia. And the gist of it is that we did it with a model that used the relationship between words in a similar way to current natural language processing models (such as chatGPT) that are used to predict which word is next in a sentence or to do translations. So, we use tools inherent to language to be able to translate in an appropriate and detailed way the structural properties of a molecule to the general universe of words, of language. What better demonstration of the existence of a close relationship between smell and language? With this we think we have shown that language and smell go hand in hand, and the idea that smell that is ineffable is wrong as it can be measured with words.

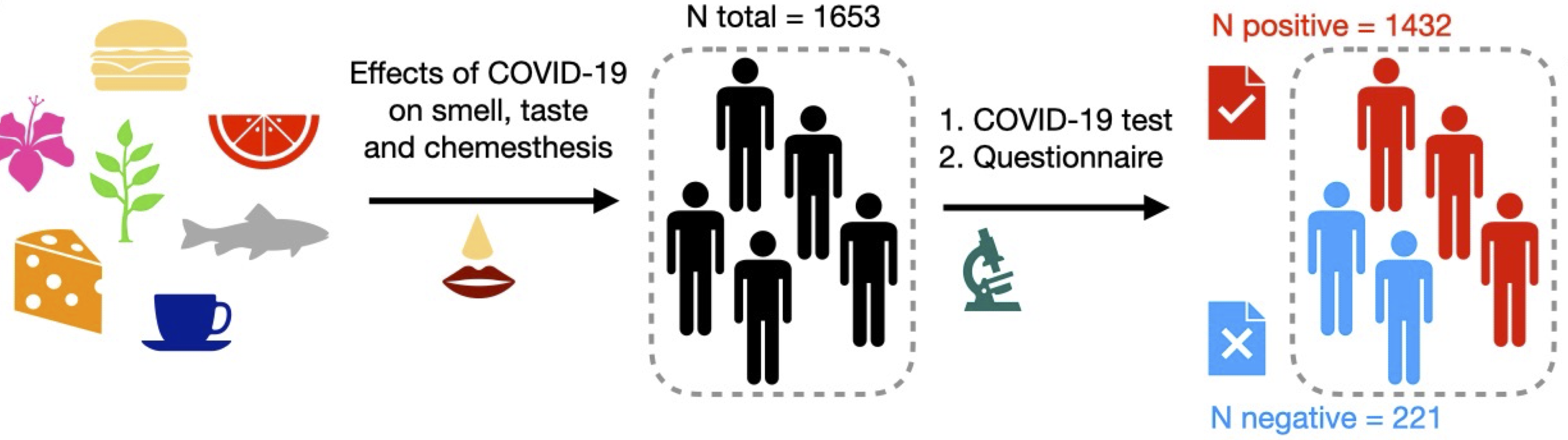

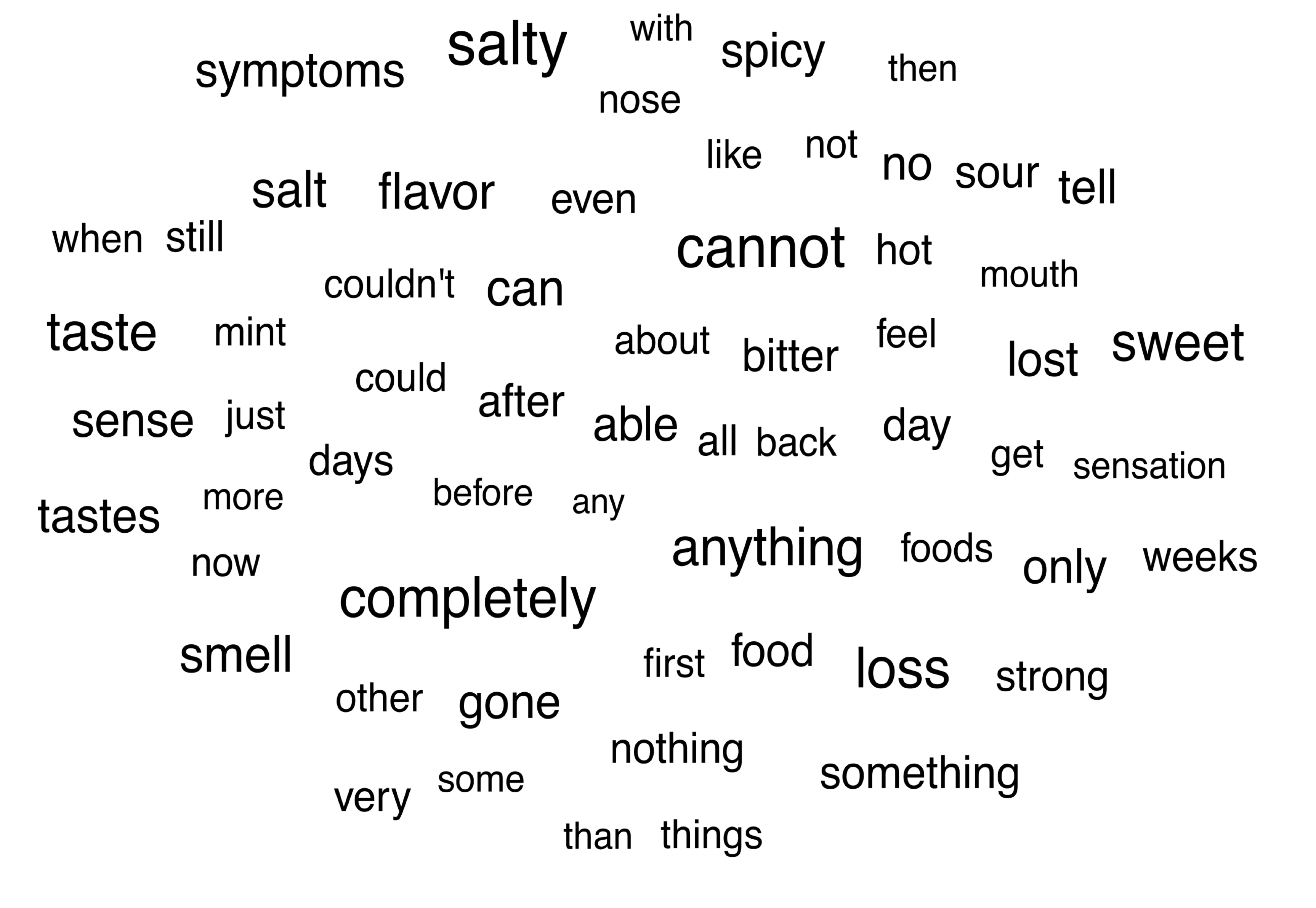

Indeed precisely in the paper now published in Comms Med, and for those who still think that smell doesn't matter, just ask those who have lost their sense of smell due to COVID during this pandemic. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 reported changes in smell and taste. To better study these symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infections and potentially use them to identify infected patients, a survey was undertaken in various countries asking people about their COVID-19 symptoms. One part of the questionnaire asked people to describe the changes in smell and taste they were experiencing. More than 1500 people responded to the questionnaire, sometimes extensively describing their chemosensory symptoms. We developed a computational program, based on fine tuning a Large Language Model (LLM) that could use these responses to correctly distinguish people that had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection from people without SARS-CoV-2 infection. This approach could allow rapid identification of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 from descriptions of their

Indeed precisely in the paper now published in Comms Med, and for those who still think that smell doesn't matter, just ask those who have lost their sense of smell due to COVID during this pandemic. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 reported changes in smell and taste. To better study these symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infections and potentially use them to identify infected patients, a survey was undertaken in various countries asking people about their COVID-19 symptoms. One part of the questionnaire asked people to describe the changes in smell and taste they were experiencing. More than 1500 people responded to the questionnaire, sometimes extensively describing their chemosensory symptoms. We developed a computational program, based on fine tuning a Large Language Model (LLM) that could use these responses to correctly distinguish people that had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection from people without SARS-CoV-2 infection. This approach could allow rapid identification of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 from descriptions of their  sensory symptoms and be adapted to identify people infected with other viruses in the future.

sensory symptoms and be adapted to identify people infected with other viruses in the future.

If you still this is still not a proof that language is an important tool for smell, just imagine a group gathered around a table and one person can't smell the food. You can't really participate in the conversation or feel connected to the shared experience that is eating. The sense of smell is uniquely purposeful and confers unique behavioral advantages that other senses cannot provide.

Our results show that the description of perceptual symptoms caused by a viral infection can be used to fine-tune an LLM to correctly predict and interpret the diagnostic status of a subject. In the future, similar models may have utility for patient verbatims from online health portals or electronic health records.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Medicine

A selective open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary across all clinical, translational, and public health research fields.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Healthy Aging

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in