Electrified Thermal Energy Storage (eTES): Turning Renewable Energy into System Flexibility

Published in Mechanical Engineering

Most thermal energy storage (TES) research still focuses on thermally charged systems, storing waste heat or renewable heat such as that from solar collectors. Yet directly electricity-charged TES is rapidly emerging as a powerful and still under-appreciated solution for a renewable-dominated grid.

In our new Nature Reviews Clean Technology paper, we formalise this paradigm for the first time as Electrified Thermal Energy Storage (eTES), moving the term beyond scattered commercial use into a coherent scientific and engineering framework for decarbonising heat, cooling and grid balancing.

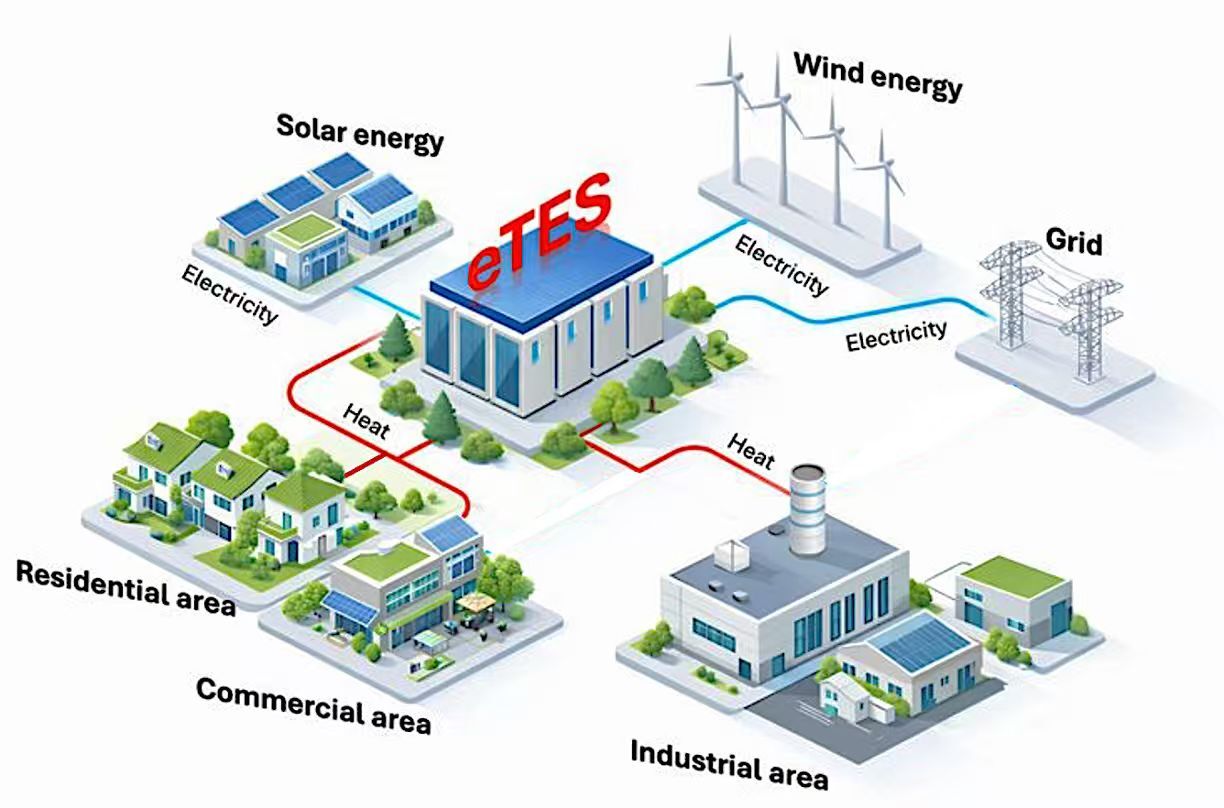

As renewable electricity generation accelerates worldwide, a central paradox is becoming increasingly clear: producing more renewable power does not automatically mean using more of it. Wind and solar output are governed by weather and daylight rather than demand, while power systems must remain balanced at every moment. Without sufficient flexibility, growing volumes of clean electricity are curtailed or wasted, even when they are abundant and cheap. In this context, the usable share of renewable energy is determined not by how much is generated, but by how effectively the energy system can shift demand in time, modulate power and store energy in different forms. This multi-dimensional system flexibility, including temporal, power and energy, is where eTES becomes critical. By converting electricity directly into heat and storing it for later use, eTES provides a scalable, low-cost and fast-responding way to absorb surplus renewable electricity and deliver it as decarbonised heating and cooling across residential, commercial and industrial sectors.

Why eTES matters

Heating accounts for around half of global final energy consumption and nearly 40% of energy-related CO₂ emissions. At the same time, investment in renewable electricity has surged, creating periods of surplus generation that the power grid struggles to absorb. Traditionally, system flexibility has been provided by fossil-fuel-based peaking plants or grid-scale electrical storage, both of which face cost, scalability, or emissions constraints.

eTES addresses this challenge by shifting part of the flexibility burden from the power sector to the demand side. Instead of curtailing renewable electricity, eTES systems can absorb excess power when it is abundant and inexpensive, convert it into thermal energy, and release it when heat is needed. In doing so, eTES effectively links renewable generation with one of the largest and most inflexible energy demands in the system: heat.

Core concept and system architecture

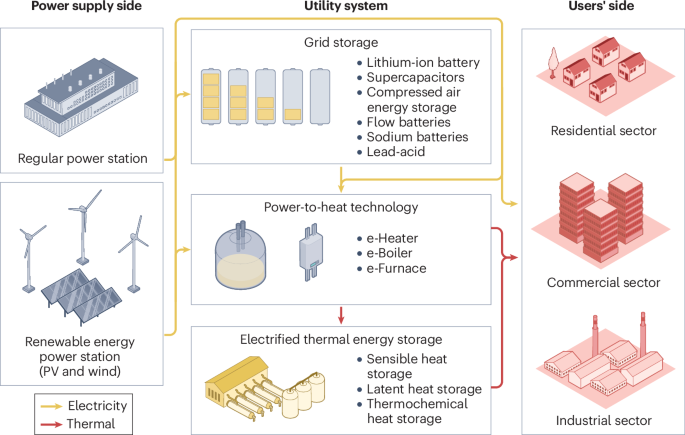

eTES consists of two tightly coupled components: direct power-to-heat conversion and thermal energy storage. Electricity is converted into heat using technologies such as resistive, ohmic, microwave, induction, or infrared heating, and the heat is stored using sensible, latent, or thermochemical storage media.

Unlike conventional electrical batteries, eTES avoids unnecessary energy conversions when the end-use demand is thermal. This leads to lower costs, simpler system designs, and high round-trip efficiencies, which often exceeding 90%, and in some thermochemical systems even surpassing 100% due to chemical heat pump effects.

Functionally, eTES behaves like an energy buffer for the grid. However, instead of stabilizing electricity alone, it provides regulation capability across both electricity and heat networks, making it a powerful tool for integrated energy systems.

Key innovations

One of the central contributions is a systematic comparison of direct electric heating technologies and their compatibility with different thermal energy storage media.

Commercially mature eTES systems typically combine resistive heating with sensible or latent heat storage. These systems are already deployed at scale in domestic water heating, district heating, and industrial process heat. They are cost-effective, robust, and fast-responding, but are generally limited to short- or medium-duration storage due to heat losses and relatively low energy density.

Beyond these established solutions, we also highlights emerging ETES pathways that significantly expand performance envelopes:

- Volumetric and non-contact heating methods, such as microwave and ohmic heating, enable rapid, uniform heating of large material volumes. This dramatically improves charging speed and responsiveness to fluctuating renewable power.

- Latent heat storage using advanced phase change materials offers higher energy density and stable output temperatures, enabling more compact systems.

- Thermochemical heat storage provides near-lossless, long-duration storage, making it particularly attractive for seasonal energy shifting and long-term flexibility.

The combination of advanced heating methods with high-density storage media opens the door to ETES systems capable of operating at temperatures ranging from domestic hot water to ultra-high-temperature industrial processes.

Regulation capability as a limiting factor for renewable utilisation

A key message is that system flexibility, rather than generation capacity, has become the primary constraint on renewable energy utilisation. As variable renewables grow, grids increasingly require fast, controllable, and affordable forms of regulation.

eTES contributes to regulation capability in several ways. First, it provides rapid demand-side response, allowing electricity consumption to follow renewable availability rather than fixed demand profiles. Second, thermal storage decouples energy conversion from energy use, enabling time-shifting from hours to months. Third, eTES reduces peak electrical loads by supplying heat from stored energy rather than real-time electricity consumption.

In this sense, eTES is not merely a heat decarbonization technology, and it is a flexibility infrastructure. By increasing the system’s ability to absorb, store, and redeploy renewable electricity, ETES directly increases the fraction of renewable generation that can be practically used.

Sectoral impacts and deployment potential

eTES deployment across residential, commercial, and industrial sectors. In residential and commercial buildings, eTES can smooth daily load profiles, reduce electricity costs through time-of-use pricing, and mitigate winter peak demand. At the community scale, shared eTES systems can significantly reduce grid congestion and infrastructure upgrade requirements.

In industry, where high-temperature heat dominates energy demand, eTES offers a particularly compelling opportunity. Many industrial processes require temperatures well above the efficient operating range of heat pumps. eTES systems based on resistive, ohmic, or microwave heating can directly deliver this heat while offering operational flexibility aligned with grid conditions.

Crucially, industrial eTES can act as a large, controllable load, providing valuable ancillary services, such as frequency regulation and load balancing, which will become increasingly important in renewable-dominated grids.

Future prospects and research directions

Looking ahead, the role of eTES is expected to grow as energy systems become more integrated and flexibility-constrained. Materials innovation is critical, particularly for improving the durability, conductivity, and cycling stability of latent and thermochemical storage media. Advanced manufacturing techniques, including additive manufacturing, may enable tailored thermal and electrical properties at scale.

System integration is another key challenge. eTES must be designed not only as a standalone technology but as part of coordinated electricity–heat–industry systems, supported by market mechanisms that value flexibility and regulation capability.

Finally, policy and market frameworks must evolve to recognize that renewable integration is fundamentally a flexibility problem. Technologies such as eTES, which enhance regulation capability while delivering useful energy services, should be incentivized accordingly.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Reviews Clean Technology

This journal publishes Reviews, Perspectives, and opinion articles on the research, development, and implementation of clean technologies and processes. It spans fields and covers solutions that connect science, technology, economics, and policy.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in