Emerging hotspots of agricultural drought under climate change

Published in Earth & Environment and Sustainability

Why we wrote this paper

The question we kept hearing wasn’t just “is drought getting worse?”, but “is this climate change — or natural variability?”, and “can we trust the climate models to project change in drought accurately at regional scale?” Because these underlying issues are shared across tropical and extra-tropical climates, we saw a need for a unified global approach grounded in process understanding.

Part of the challenge is that “drought” can mean different things: meteorological drought (rainfall deficit), hydrological drought (streamflow and storage deficit), or agricultural drought (soil moisture deficit). In this paper we focus on agricultural drought, because of its links to the land-surface water balance, and ultimately to food security. For agriculture, the season matters. Most crops are not grown year-round, and the impacts that translate into yield losses are tied to soil moisture deficits during the local growing season. This means important changes can be missed by annual metrics.

So the motivation was twofold: first, to treat agricultural drought explicitly as a growing-season phenomenon shaped by both in-season weather anomalies and antecedent conditions (how wet the soil is at the beginning of the season). Second, to build a framework that could be applied consistently across both the tropics and the extra-tropics. That required defining growing seasons regionally: in the northern-hemisphere extra-tropics we use May–September, while in the tropics we align growing seasons with wet seasons using an objective method based on cumulative rainfall anomalies.

A process “lens”: controls on the land-surface water balance

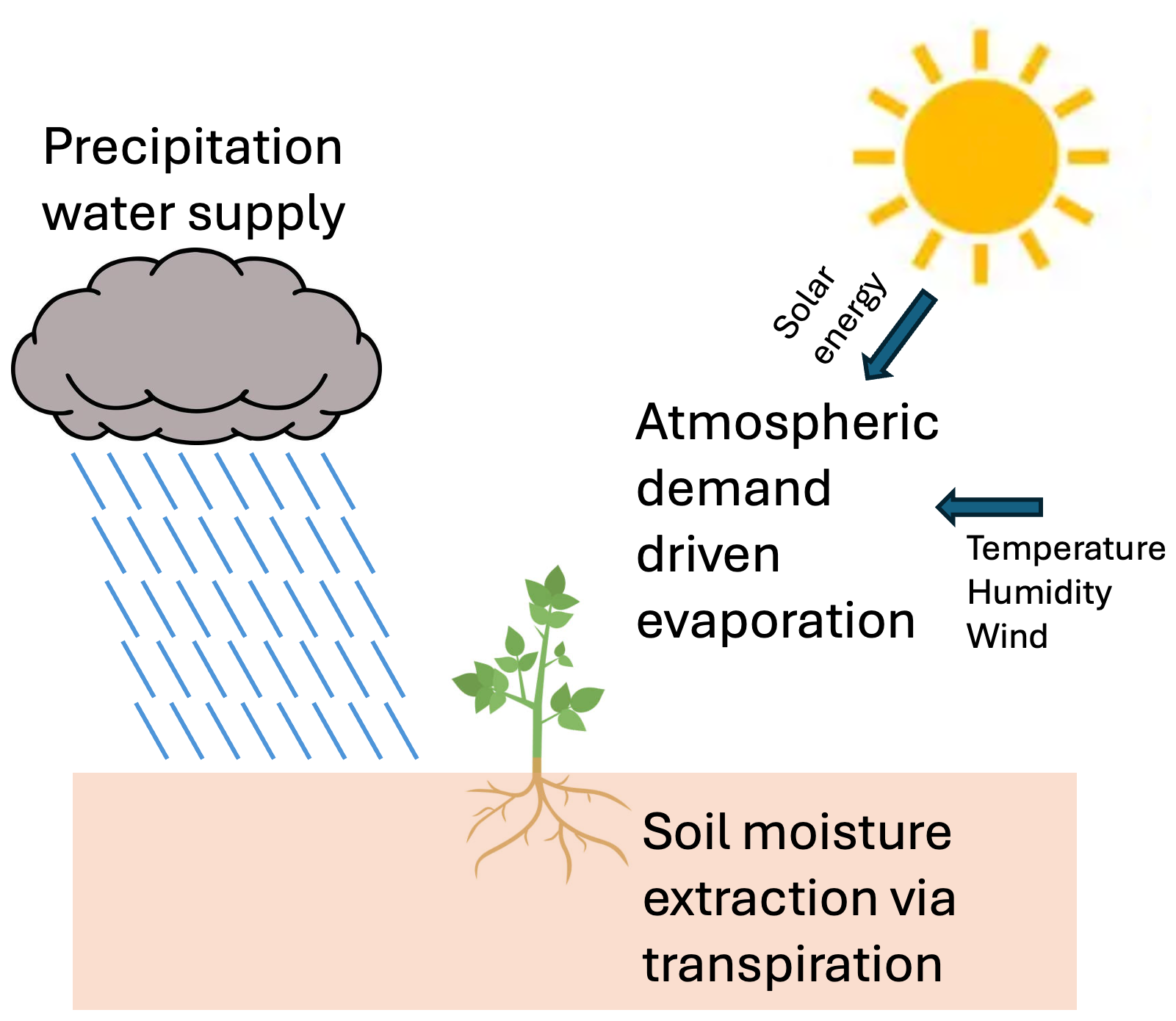

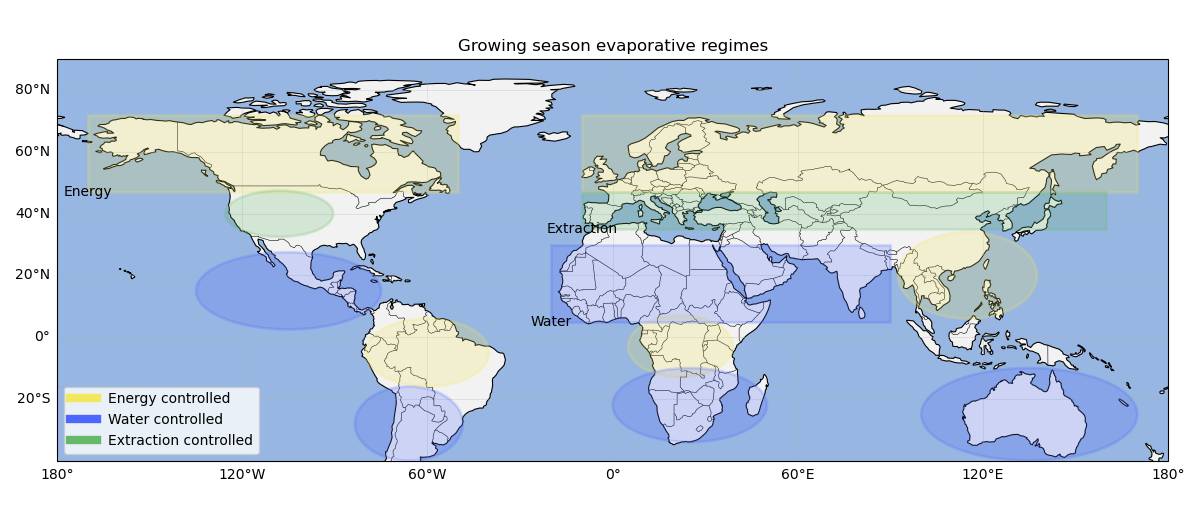

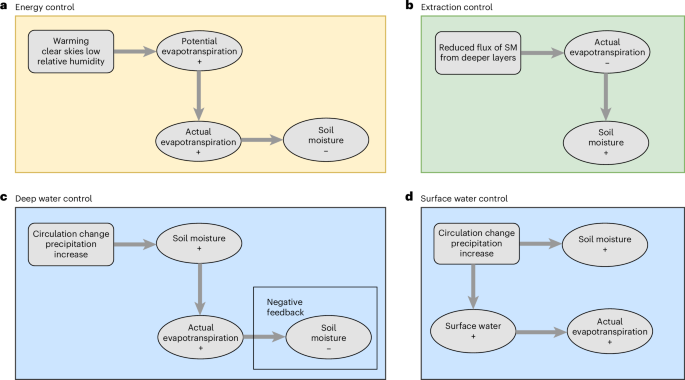

Our starting point is the land-surface water balance. Over a growing season, soil moisture changes according to what comes in (precipitation) and what leaves (primarily evaporation, but also drainage and runoff). The global land-surface water balance is modulated by spatial and seasonal shifts in the controls on evaporation – i.e. evaporative regime. In water-controlled regimes, evaporative losses are controlled by moisture supply, so evaporation tends to track rainfall and replenishment. In energy-controlled regimes, in which water is abundant or solar energy is low, evaporation is determined mainly by atmospheric evaporative demand, which depends on solar energy, temperature, humidity and other meteorological variables. In this study, we extend this classic framework with a third regime that is especially relevant for agriculture: an extraction-controlled regime, where seasonal evaporation is governed by plant access to and extraction from the root zone, rather than by precipitation supply or atmospheric demand alone. This matters because misclassifying extraction control can distort interpretation — either overstating demand-driven effects or tying future risk too tightly to uncertain precipitation changes. These processes and the global distribution of regimes are shown in Figures 1 and 2 below.

Figure 2 Distribution of growing season evaporative regimes in the tropics and northern hemisphere extra-tropics

A second key process is soil moisture memory — the persistence of wet or dry anomalies over months to years. Because of this persistence, agricultural drought in any given season is shaped by soil moisture at season onset (antecedent conditions) as well as within-season accumulation. In our results, long-term changes in growing-season soil moisture are more strongly explained by shifts in antecedent conditions than by changes in within-season accumulation, consistent with an important role for memory. In the tropics, we found that soil moisture memory reflects long-term change in the land-surface water balance; in the northern hemisphere extra-tropics, memory is linked to variability during the preceding spring.

So what did we find?

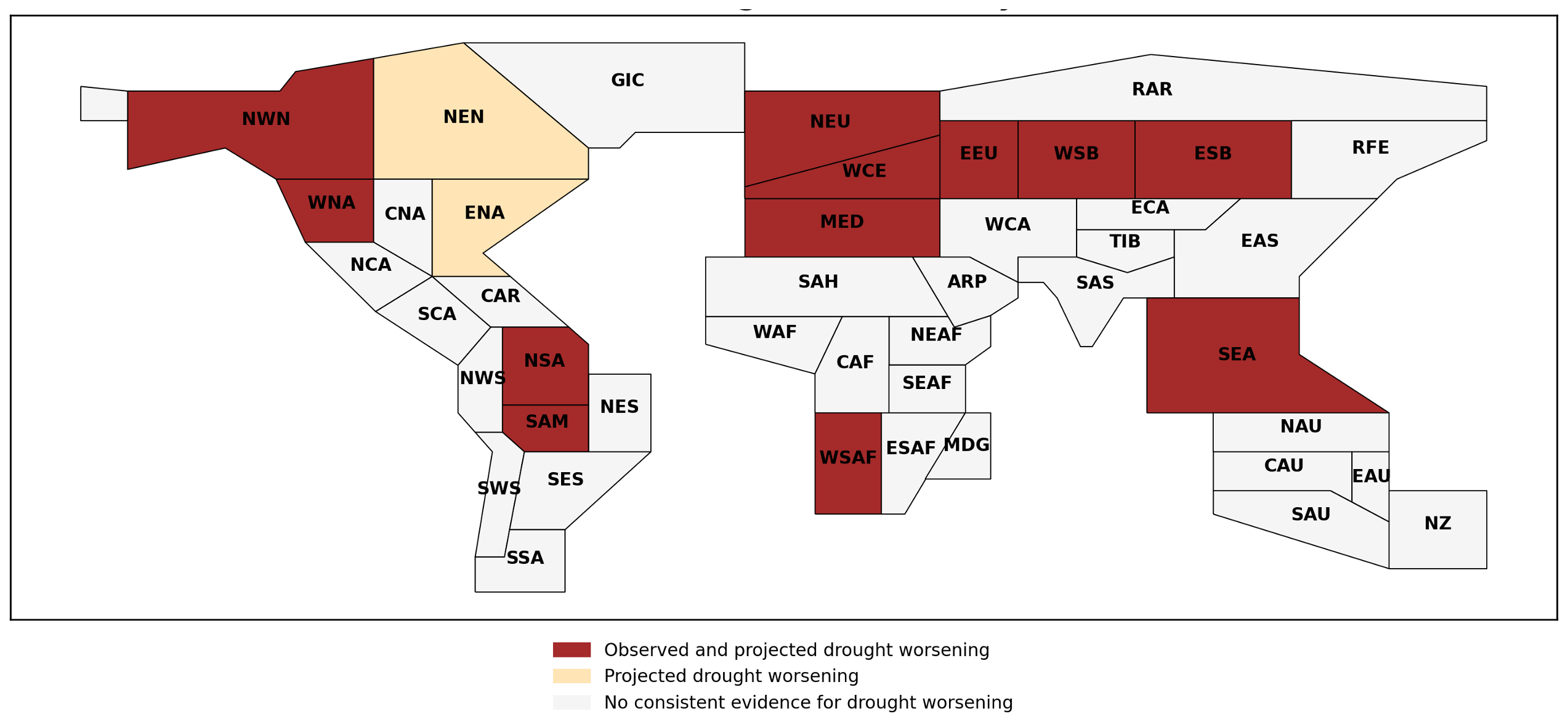

Using this process-based framing, we identify emerging hotspots where historical observations and future projections align on worsening agricultural drought. These include western North America, western Europe, and mid-latitude central and eastern Europe (with some regional exceptions), and — outside the northern extra-tropics — western southern Africa and parts of Amazonia and northern South America (see map in Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: Summary of emerging hotspots of agricultural drought. The dark brown shading denotes emerging hot spots, the light brown regions indicate that drought is projected to worsen, but that there is no clear signal yet in the historical record. The regions shown were used in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment report (https://github.com/IPCC-WG1/Atlas).

Equally important are regions that do not meet this “emerging hotspot” criteria. In the Horn of Africa, for example, the historical record shows increased agricultural drought linked to observed precipitation droughts, yet projections indicate anthropogenic rainfall increases that would reduce drought incidence in the future. In this framing, observed drying there cannot be treated as an indicator of future change.

Behind the scenes: developing a coherent narrative and dealing with large datasets

Submitting to a high-impact journal requires not only a novel contribution, but a clear message with broad relevance. The first draft tried to do too much: too many regional digressions, too many alternative metrics, too many side-quests into evaluation. Over the course of my sabbatical year (and through twelve full re-writes!), I sharpened the paper around a coherent narrative: where agricultural drought is emerging now, how it is likely to evolve, and how these changes can be framed in the context of evaporative regimes and soil moisture memory.

The data challenges also shaped the final paper. Choices like working at monthly resolution, regridding model and observational data consistently, and building an objective growing-season framework were not just methodological decisions — they were practical strategies that made the analysis transparent and scalable.

A personal perspective

I have worked on drought and heatwaves for more than twenty years, maintaining a deep focus on Africa, but also increasingly drawn into drought risk across the northern hemisphere extra-tropics. Over that time, I have become more and more convinced that we need a framework that unites tropical and extra-tropical processes — not by pretending they are the same, but by giving ourselves a consistent way to ask what controls the land-surface water balance in each place and season.

I also wanted this work to speak to the current climate emergency. Climate change is often portrayed as something that will happen later, but many communities are experiencing shifting drought characteristics now. Identifying “emerging hotspots” is an attempt to connect projections to what we can already observe — and to separate signals that are likely to intensify from those that may not.

My interests are rooted in impact, and particularly in food security. But to interpret projections on multi-decadal timescales — and to connect them to historical observations — we need more than headline trends in precipitation and temperature. We need rigorous understanding of the processes that control evaporation, soil-moisture persistence, and the seasonal pathways that underpin drought risk. That process understanding is not a curiosity driven indulgence: it is what turns climate model output into something decision-makers can use with confidence for both adaptation and mitigation of climate change.

Research team

The paper discussed in this blog was co-authored by Emily Black, Caroline Wainwright, Richard Allan and Pier Luigi Vidale. Emily led the work and wrote the paper; Caroline developed the method for objectively identifying tropical rainfall seasonal cycles; and the study’s ideas on drought, soil-moisture memory and the land-surface water balance grew out of many years of discussion between Emily, Richard and Pier Luigi.

Further information

To find out more about this work, have a look at our paper: DOI:10.1038/s41561-025-01898-8

(available to read here: https://rdcu.be/eY1a6)

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Geoscience

A monthly multi-disciplinary journal aimed at bringing together top-quality research across the entire spectrum of the Earth Sciences along with relevant work in related areas.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Fluids in seismicity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Past sea level and ice sheet change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in