Explore the Research

Etiology of TP53 mutated complex karyotype acute myeloid leukemia - Leukemia

Leukemia - Etiology of TP53 mutated complex karyotype acute myeloid leukemia

From a genetic perspective, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is an unusually “clean” malignancy: it typically carries relatively few driver mutations, has a strong epigenetic component, and shows minimal karyotypic disruption. Yet one subtype—complex karyotype AML (CK-AML)—breaks all these conventions. Patients diagnosed with CK-AML face substantially poorer event-free and overall survival compared with those with normal-karyotype AML. Fortunately, CK-AML is relatively rare; unfortunately, this rarity has also meant it is far less studied and understood.

A Research Question Born in the Mountains

Two of us are siblings, and during summer hikes in the Alps we often talk about family, life—and science. One recurring topic was CK-AML, spurred in part by previous work on marker chromosomes. The literature had established that roughly half of CK-AML patients harbor TP53 mutations, which could help explain the extensive chromosomal abnormalities. But what about the other half? We did not have a satisfying answer.

A False Start

Around that time, two independent studies from China suggested that TET dioxygenases—then the favorite proteins of one of us—might participate in DNA-damage checkpoint signaling. One paralogue, TET2, was already implicated in normal-karyotype AML. Our working hypothesis emerged: could TET mutations drive chromosomal instability in CK-AML cases lacking TP53 mutations?

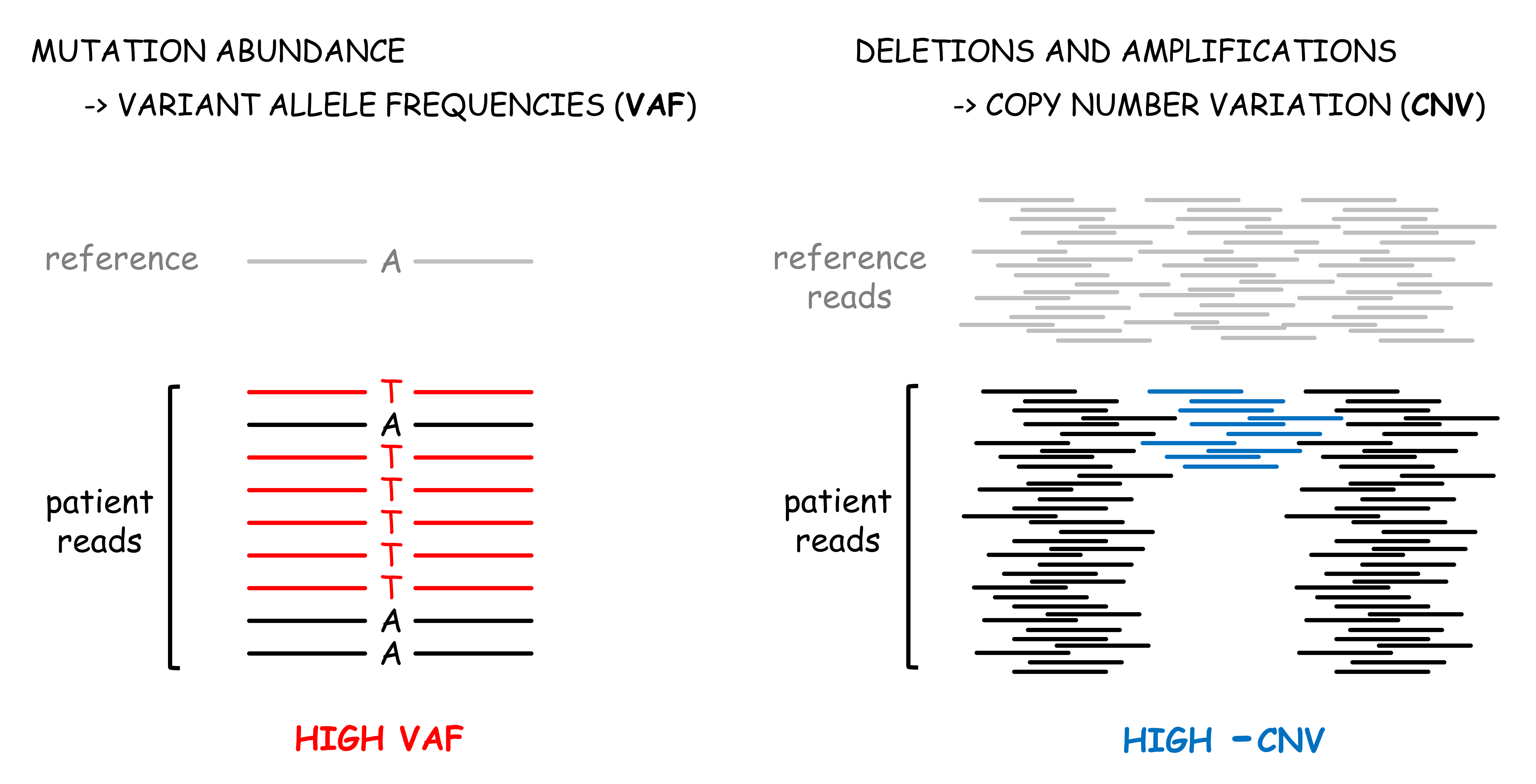

The clinicians among us gathered bone marrow or blood samples from CK-AML patients, with consent appropriate for the project. Strictly speaking, exome sequencing alone would have sufficed to test our hypothesis. But because a combined exome–copy number variation (CNV) kit was readily available, we opted to collect CNV data as well, hoping for deeper insights into the chromosomal rearrangements characteristic of CK-AML.

To our disappointment, CK-AML samples tended to carry fewer TET mutations rather than more. We were clearly on the wrong track. In retrospect, scientific affection can bias judgement—one can easily overestimate the relevance of one's favorite protein.

A New Direction and Key Insight

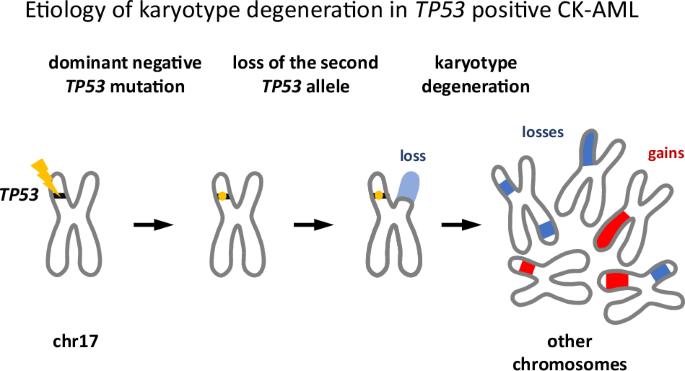

Despite the setback, the decision to collect CNV data turned out to be crucial. We noticed that in nearly all TP53-mutant cases, the missense mutation in one allele was accompanied by a deletion of the other allele. Moreover, most TP53 mutations we identified were well-known variants—suggesting they conferred either gain-of-function or dominant-negative activity. Given the chromosomal chaos of CK-AML, the latter was far more plausible, consistent with prior studies and database annotations.

This led to a compelling scenario for CK-AML development. First, a TP53 mutation arises in a hematopoietic cell. If the mutation is not dominant negative, the cell may not progress to CK-AML—or at least not rapidly, and the affected individual will not show up in our cohort. But when it is dominant negative, partial loss of TP53 function weakens checkpoint signaling, predisposing the cell to chromosomal instability, including the loss of the remaining wild-type allele, causing disease and clinical detection.

Mechanistically, this loss should be advantageous for an emerging leukemic clone. As TP53 functions as an oligomer, even a single remaining wild-type allele could sustain some residual checkpoint activity. Deleting it eliminates this last safeguard.

Mathematics to the Rescue

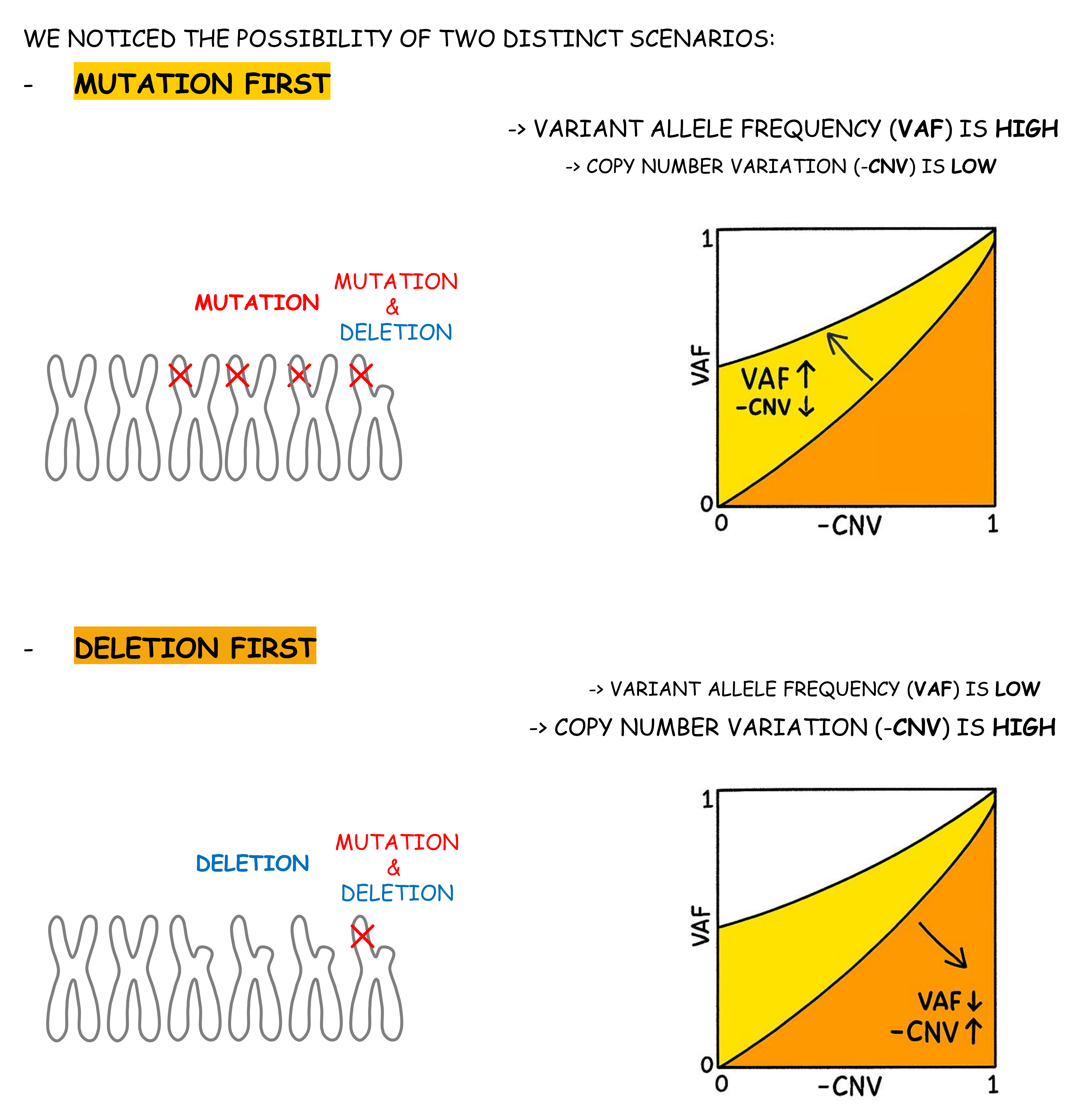

Taken together, our data suggested a “mutation-first, deletion-second” model. But could we prove it? Ideally, one would resolve clonal evolution using single-cell sequencing. But many of our samples predated the advent of such technology, and others had been preserved in ways incompatible with single-cell workflows. Was our hypothesis doomed?

Not quite. With several reasonable assumptions, namely, that TP53 alterations did not arise independently in separate clones, and that no patient lost more than one allele (owing to linkage with an essential nearby gene)—bulk data could still be informative.

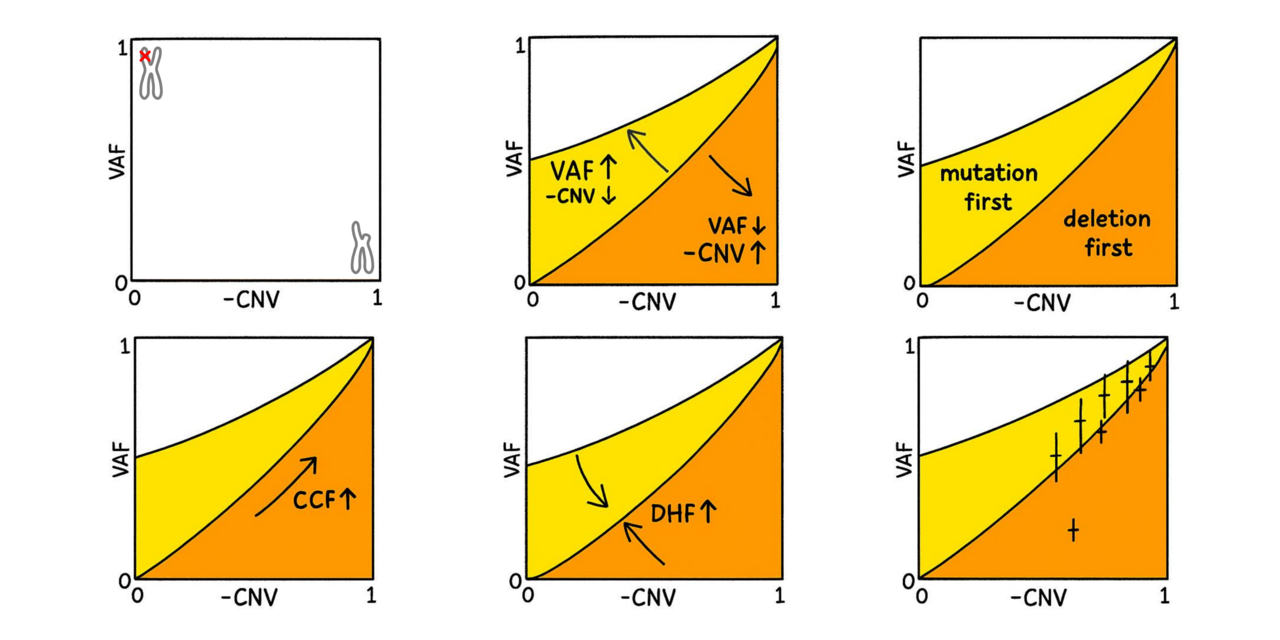

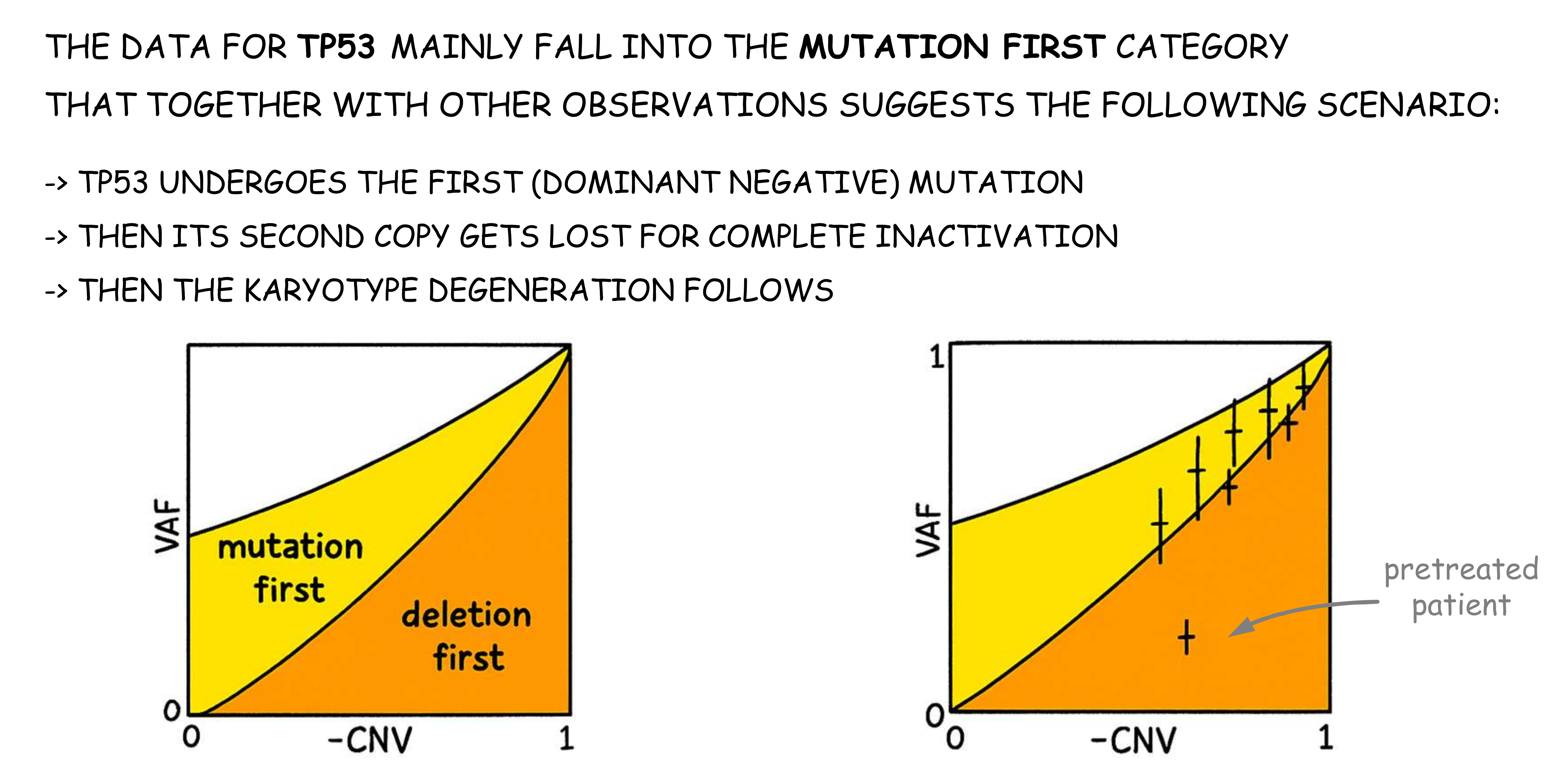

Conceptually, a high variant allele frequency (VAF) combined with modest CNV supports the mutation first scenario, whereas a low VAF and deeply negative CNV speaks for the deletion happening first.

Because CNV values are logarithmic and influence how VAF should be interpreted (fewer wild-type alleles are present), some mathematics is needed to determine the precise boundary between the two scenarios. And fortunately, our sequencing data was deep enough to give us sufficiently accurate VAF values.

Gratifyingly, the data supported the “mutation first” scenario for most patients. The only clear outlier was a pretreated patient, likely carrying therapy-induced chromosomal alterations.

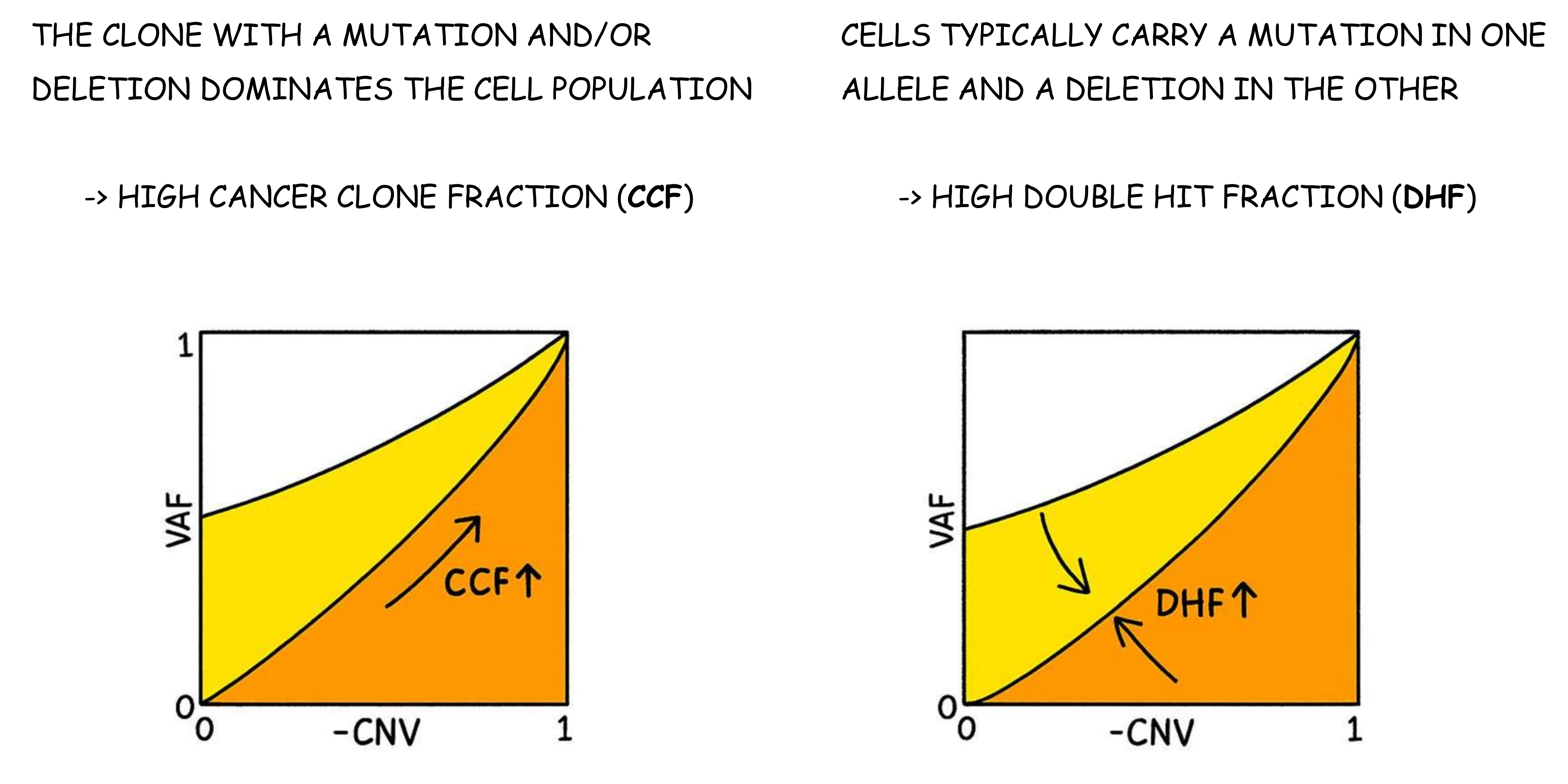

As expected, only a fraction of the cells in the samples (the cancer clone fraction, CCF) had TP53 damage. In these cells both TP53 alleles were typically affected (double hit fraction, DHF, close to 1). This finding indicates that the first and second hits occurred in close succession, or that the second hit provided a substantial proliferative advantage for the doubly hit cells.

No Story Is Ever Complete

Although we are pleased with the arc of this project, we still do not know how the karyotype instability arises in CK-AML patients without TP53 mutation. Hopefully, more hiking and discussions will spark new ideas.

Follow the Topic

-

Leukemia

This journal publishes high quality, peer reviewed research that covers all aspects of the research and treatment of leukemia and allied diseases. Topics of interest include oncogenes, growth factors, stem cells, leukemia genomics, cell cycle, signal transduction and molecular targets for therapy.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in