How many species of tree inhabit the Amazon?

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Explore the Research

Biased-corrected richness estimates for the Amazonian tree flora - Scientific Reports

Scientific Reports - Biased-corrected richness estimates for the Amazonian tree flora

Imagine trying to estimate the total number of species in one of the most species rich areas on Earth when you sample just 0.00035% of the whole area. With a writing team (Hans ter Steege, Paulo Prado, Renato Lima and Edwin Pos), backed up by 200 collaborators of the Amazon Tree Diversity Network, making use of nearly 2000 forest plots of the network, an updated tree taxonomy and some nifty mathematics we dared to do exactly that.

In May 2018, I wrote a mail to Paulo, Renato and Edwin: "What I would like to do is write a short paper to discuss the theories that are, arguably, capable of doing species richness estimation for an area the size of the Amazon, discuss their assumptions, strengths and weaknesses and do the math. Would you guys be interested to share ideas and join in this endeavor?". "Sure" they replied - and then (after the agreement of our Network) began a long but really pleasant journey.

The journey got into higher gears when I was in Ecuador attending the “Latin-American Congress of Botany”. By email, Oliver Phillips asked: "Is 5000 species in nearly 2000 forest plots not too few?". (In our nearly 2000 plots we have identified about 5000 species of tree!)

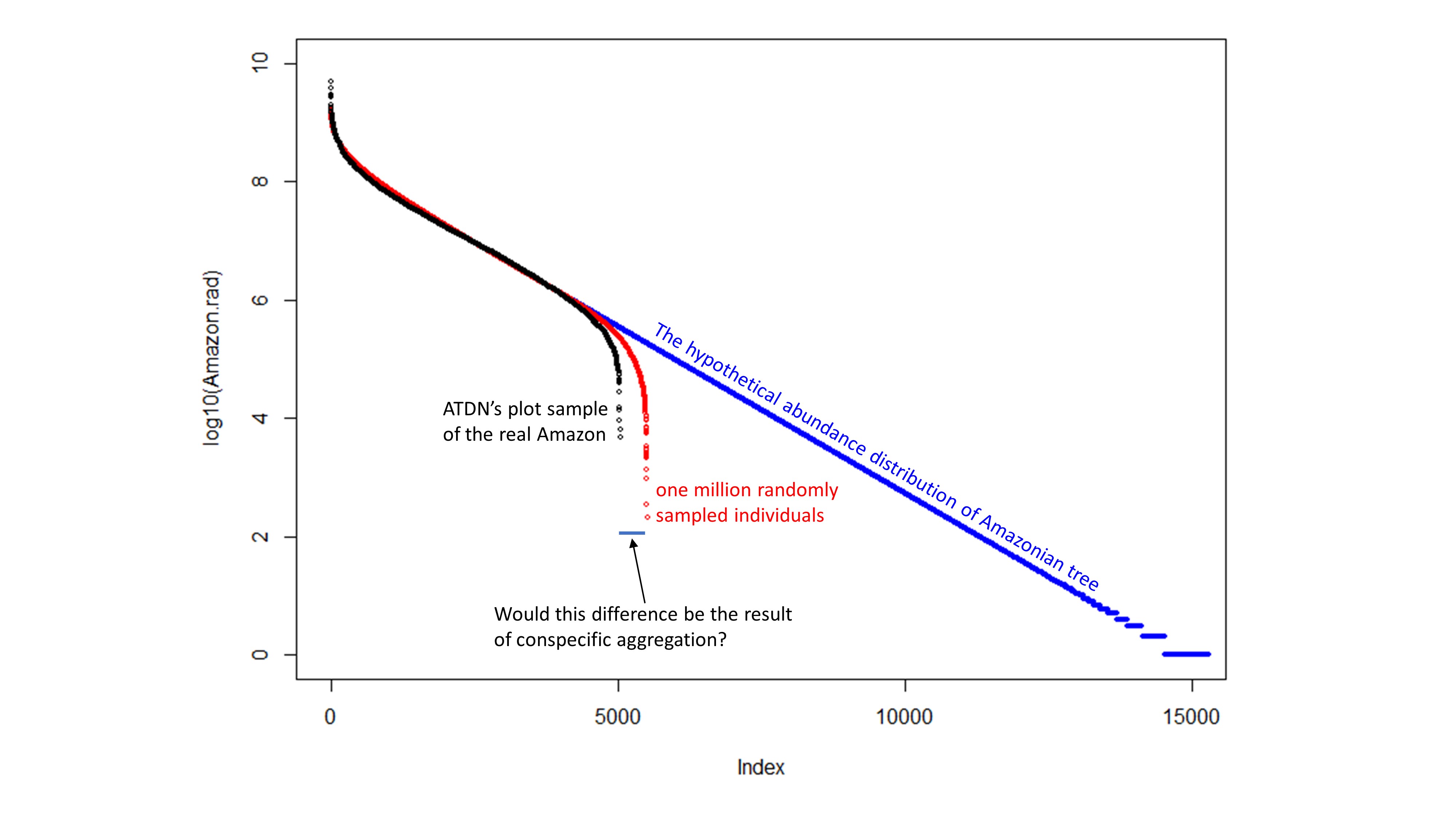

Oliver's question put me behind my desk in the small hotel room, which I shared with Renato, simulating the inventorying of ~2000 random plots from a hypothetical logseries SAD (Species Abundance Distribution) for the Amazon forest. The answer was no - 5000 species in 2000 forest plots is not too few. Assuming a completely mixed Amazon forest, with a SAD following an ideal logseries distribution, 5500 species were to be expected in our plots (~1,000,000 trees). The difference of just 10% is likely caused by conspecific aggregation (trees species tend to clump together!). I mailed this to Paulo, who in a short while improved the scripts to produce the basin-wide Amazon SAD and wrote an novel analytical solution to the species aggregation problem as well.

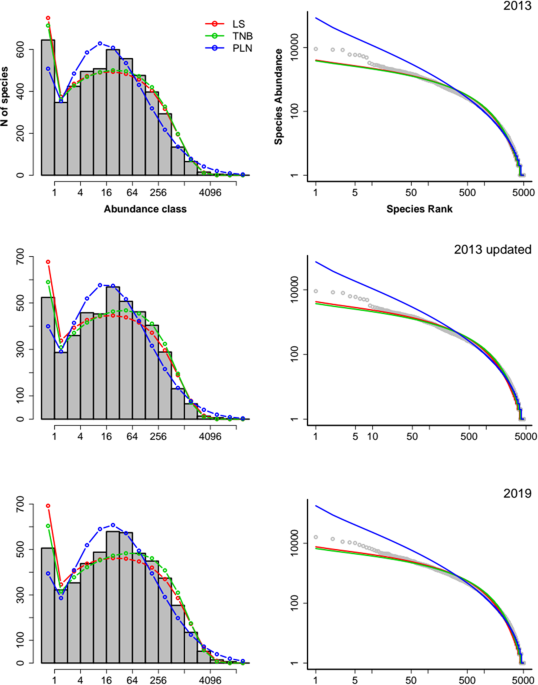

We estimated, with several different methods, the species richness for the situation back in 2013 (with “just” 1190 plots and the taxonomy accepted at that time and the current taxonomy) and compared this with the current taxonomy and the additional plots collected in the past six years (adding up to 1945 plots). An interesting finding was that neither the number of plots, nor the taxonomy mattered much for the total species estimates. Now, tell that to a biologist! As it turns out, the chosen method of estimation was more important, with differences running up to 2,000 species. Although this might be just 15-20% of the total Amazon tree flora, it is much larger than the total temperate tree flora of Northern America and Europe combined! By cleverly averaging several methods to estimate total richness, we confirm that over 15,000 tree species are expected to occur in Amazonia. We also showed that if we would manage to increase ten times the number of forest plots available, the species number in all of our plots would be 7,200, that is only 50% of the 15,000 estimated species. Although this might sound discouraging, without fieldwork there would be no data at all. Hundreds of botanists, plant and animal ecologist have spent countless hours in the field and herbaria to produce a database of plots needed for this and future work.

What did we learn? First, that rigorous plant collecting and plot establishment will lead to a higher number of known tree species, many new to science. Second, that the number of tree species in Amazonia will remain an estimate for years to come but that 15,000 species is a robust estimate. Thirdly, as individuals scientists, we are always encouraged to think and work "out of the box". But sometimes it is better to find someone who is already in that other box far away. Only a collaboration of the hundreds of botanists, field and community ecologists, field assistants, and students of the Amazon Tree Diversity Network and the mathematically inclined biologists enabled us to pull off this work. Only such collaborations between scientists of different fields can bring us further in understanding one of the most diverse systems on the planet.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Obesity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 24, 2026

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in