Hydrogel–elastomer-based conductive nanomembranes for soft bioelectronics

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology, Materials, and Biomedical Research

Our bodies are made of soft, living organs that never stop moving. Every heartbeat, every step we take, every flicker of neural activity carries more than just function – it is rich with signals of life. Biological signals have intrigued scientists for centuries, but conventional bulky, rigid electrodes have always made it difficult to interact with the body naturally. Today, inspired by unconventional approaches such as conformal epidermal electronics (Science 333, 838-843, 2011) and lightweight nanomeshes (Nature Nanotechnology 12, 907-913, 2017), we are able to monitor these biological signals in ways that feel almost mechanically “invisible” – electronics that bend, stretch, and breathe with the skin. As a research group working on soft materials – especially adhesive hydrogels combined with self-healing polymers, we have explored how hydrogel–elastomer bilayers can serve as a stress-free, tissue-friendly interface that connect the human body and synthetic electronics. Among many classes of engineering materials, hydrogel–elastomer bilayers – with mussel-inspired tissue-adhesive hydrogels, rich in water and able to stick firmly to tissues, and viscoelastic, self-healing polymers that can release stress over time – show great promise as ideal tissue-interfacing materials owing to their unique stress relaxation, morphological adaptability, biocompatibility, and engineering versatility. As an early attempt, we proposed the concept of conformal sutureless, shape-morphing bioelectronics (Nature Electronics 6, 779-789, 2023; Nature Electronics 7, 800-814, 2024), but with a lot of room for further development and exploration.

During the preparation of our recent review on tissue-adhesive bioelectronics (Med-X 3, 11, 2025), we were excited about the promising potential of organic or composite conductive nanomembranes to be made stretchable and conformable in closed-loop therapy. However, at the same time, we confronted a limitation – why most of existing organic conductive nanomembranes typically rely on a polymer substrate (much thicker than the conductive nanomembranes with a larger bending stiffness and poor conformability and adaptability to the dynamically evolving biological structures) to maintain mechanical robustness? This technological void for free-standing, intrinsically stretchable organic conductive nanomembranes that no longer rely on supporting substrates without compromising electrical performance, immediately caught our attention. Among many organic conductive nanomembranes, we focused on the glycolated bithiophene (g2T), one of the most widely studied conducting polymers in the field of bioelectronics [i.e., organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs)] owing to its advantages such as high ion–electron conduction, mechanical and electrochemical stability, ease in preparation, and good biocompatibility. Notably, we investigated a newly developed selenium-substituted derivative [P(g2T2-Se)], in which the incorporation of selenium into the conjugated backbone endows the polymer with higher polarizability, stronger intermolecular packing, and delivers superior electrochemical performance – key qualities for realizing truly free-standing and conformable bioelectronic nanomembranes.

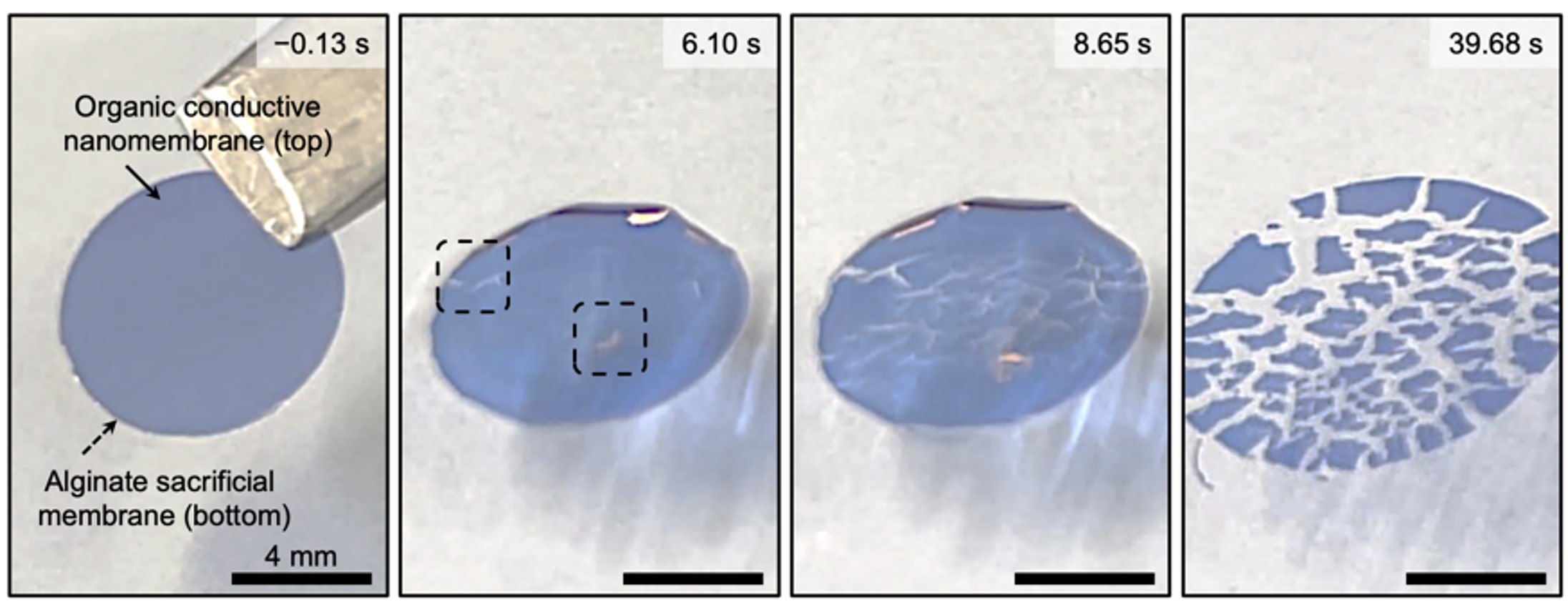

To better understand the challenge, we first studied possible reasons for the lack of free-standing capability in existing organic conductive nanomembranes. Interestingly, we found that the majority of them lack sufficient hardness – when detached from the mother substrate, the fragile nanomembranes tend to crumple and collapse onto themselves, much like a piece of wet tissue paper that folds and wrinkles without structural support. This fact leads us to hypothesize that sufficiently hard to maintain integrity during handling, yet capable of softening and lowering stiffness upon contact with biological tissue to yield transformable and imperceptible conductive nanomembranes might significantly improve microscopic conformability without compromising the electrical performance. However, like every experiment in research projects, experimentally realizing this hypothesis was not trivial. Pristine organic conductive nanomembranes couldn’t form a stable structure in wet environments and readily fragmented even when supported by a water-soluble sacrificial membrane (Fig. 1). The use of various sacrificial membranes encountered a complicated problem of removing the sacrificial membrane to achieve free-standing organic conductive nanomembranes without affecting conformability and ion–electron conduction between membrane and tissue surface. After many unsuccessful trials, we found that this simple yet enticing concept of transformable and imperceptible free-standing organic conductive nanomembranes was actually quite hard to realize.

Fig. 1 | Pristine organic conductive nanomembrane on sacrificial membrane (Alginate) is unstable in aqueous environments, readily dissociating into fragmented parts.

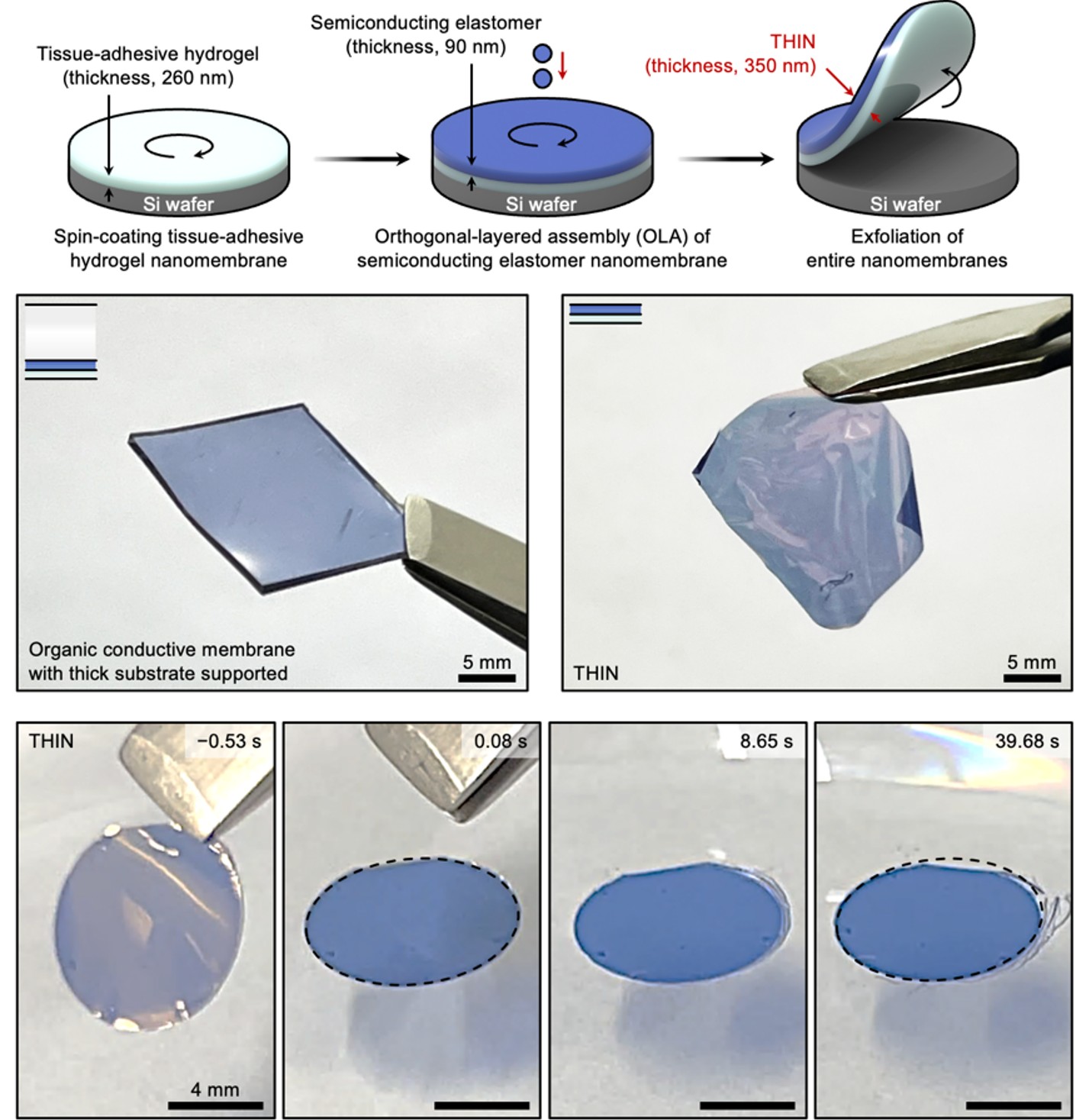

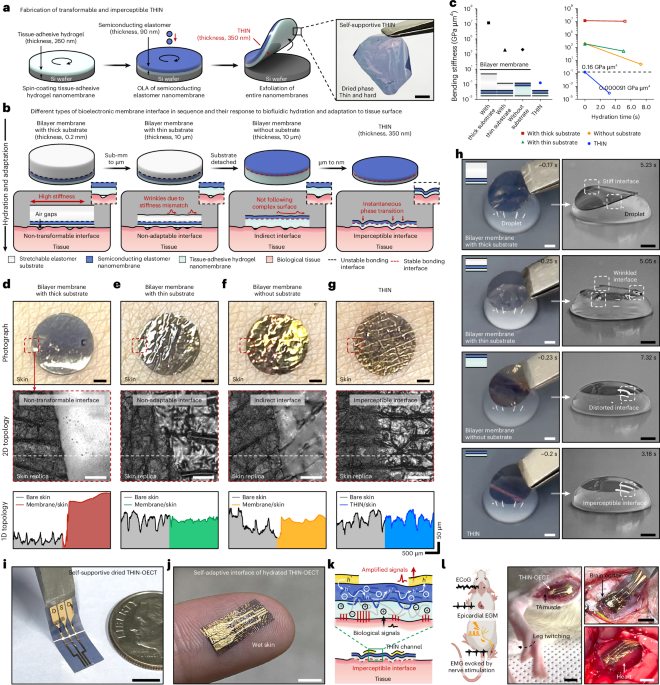

A solution came rather unexpectedly. At that moment, we were working on other projects on strain-gradient structure of adhesive hydrogel–self-healing polymer bilayer based on dried aqueous hydrogel solutions onto polymer to prepare mechanically robust hydrogel–elastomer interface (Advanced Materials 36, 2307810, 2024). Inspired by the amphiphilic design strategies in these projects, we tried a very simple experiment – instead of dissolving the water-soluble sacrificial membrane, we preserved its structure as a biofluid reservoir and fabricated it into a dried membrane only a few hundred nanometers thick. At this scale, the nanomembrane could physically adhere to surfaces while also forming strong chemical adhesion through mussel-inspired chemistry. Even more importantly, the nanomembrane created a shortened effective distance between the tissue surface and the conducting channel. Taking advantage of orthogonal solvents, we developed an orthogonal-layered assembly that allowed us to deposit the organic conductive nanomembrane seamlessly on top – enabling multiple interactions and a stable, free-standing structure (Fig. 2). To our surprise, we could get dried hard nanomembranes that swelled into stable soft tissue interface while reserving mobile ions within biofluid-rich tissue-adhesive hydrogel matrix (transitioning from a hardness of 1.35 to 0.035 GPa and a stiffness of 0.16 to 9.08×10-5 GPa μm4). A bigger surprise came when we measured the interfacial contact impedance of these conformable conductive nanomembranes on skin – the interface resistance could reach 0.042 MΩ and 11.98 nF, orders of magnitude superior to that of substrate-supported organic conductive membrane (24.41 MΩ and 0.24 nF each)! After the moment of surprise, we realized with excitement that we found a way to materialize our hypothesis and achieved transformable and imperceptible hydrogel–elastomer adhesive bilayer based on ionic–electronic conductive nanomembranes (THIN) with a thickness of 350 nm. The THIN was highly stable in aqueous conditions due to the robust interaction between hydrogel and elastomer (Fig. 2, bottom).

Fig. 2 | Fabrication process (top) for transformable and imperceptible hydrogel–elastomer adhesive bilayer based on ionic–electronic conductive nanomembranes (THIN) with a thickness of 350 nm. Highly stiff conducting membranes with substrate supported (middle, left) and THIN (middle, right). Mechanical stability of THIN in aqueous environments (bottom).

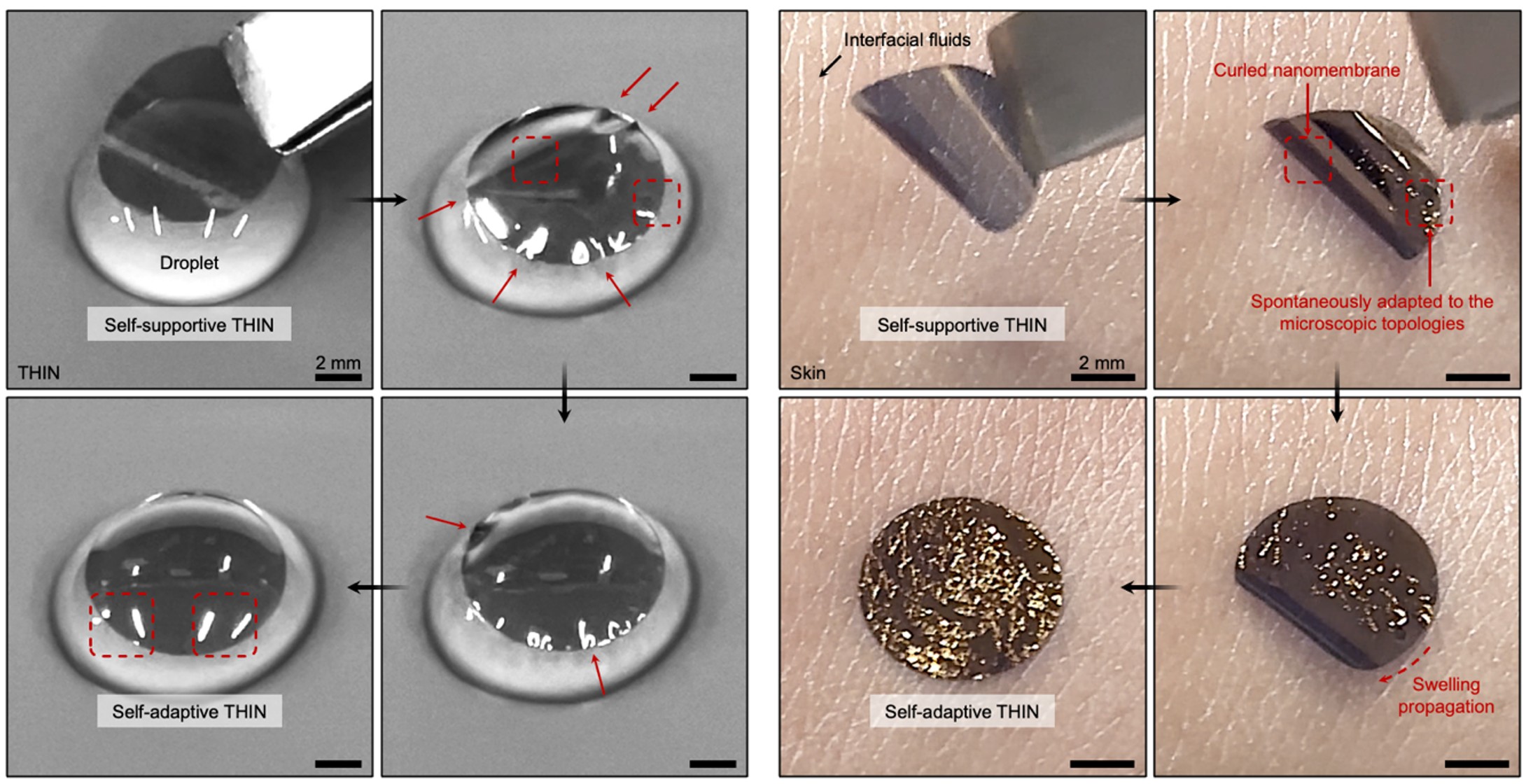

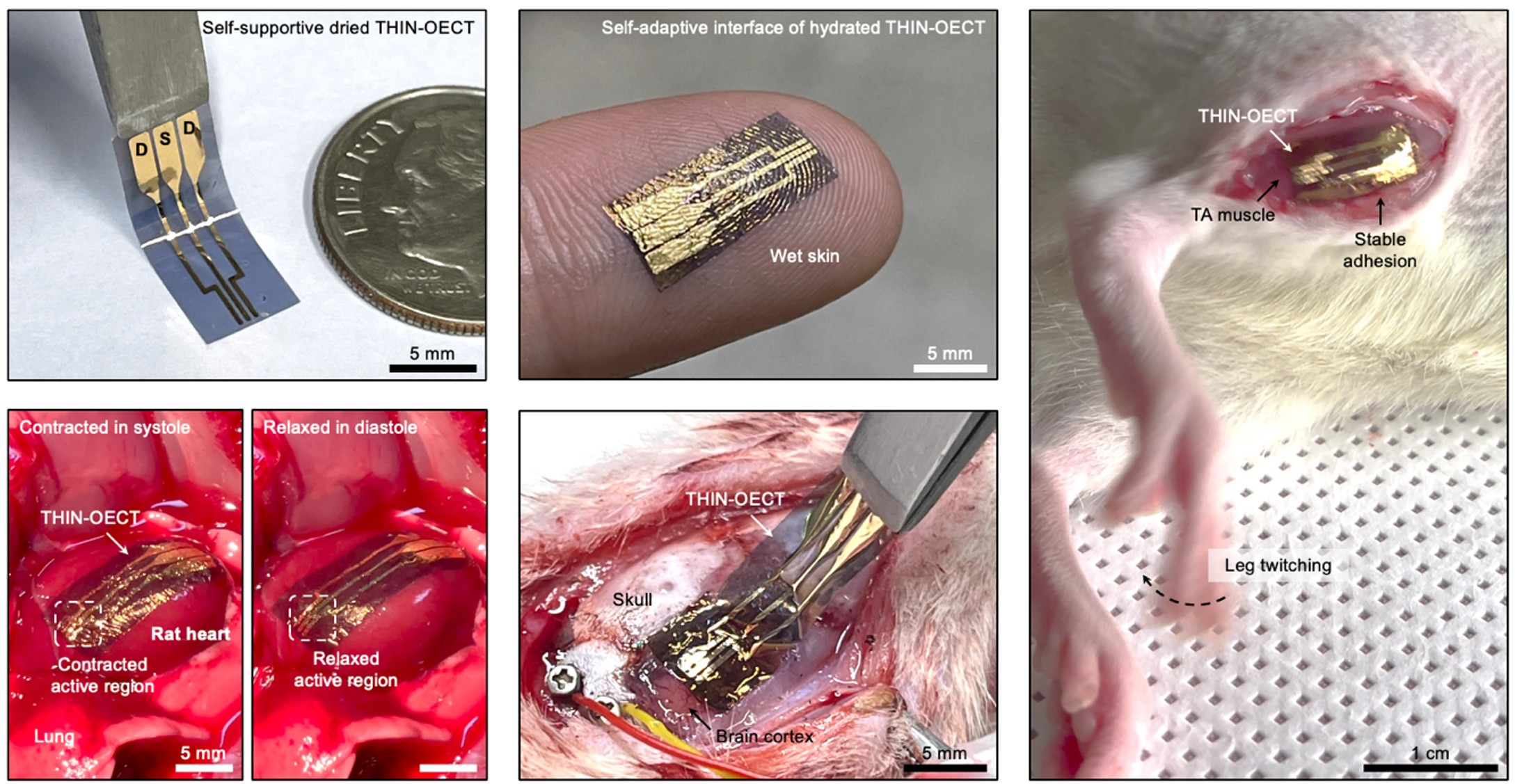

After a series of characterizations and analyses, we found that the direct spin-coating of the organic conductor solution via orthogonal-layered assembly did a similar job to spin-coating on conventional wafers – maturation and arrangement of edge-on ordering of crystalline conductive nanomembranes, which resulted in greatly enhanced ion–electron conduction and mechanical properties as well as stability. Furthermore, we also discovered a novel phenomenon – swelling behavior of tissue-adhesive hydrogel nanomembrane could self-adapt owing to the amphiphilic nature of THIN! As the mechanical neutral axis of THIN became off-centre during the hydration process in wet environment, the asymmetric swelling significantly influenced its deformation (Fig. 3). We further demonstrated that this unique transformable behavior can be particularly beneficial for handling and conformable adaptation of bioelectronic nanomembrane devices (THIN-OECT) by avoiding in-plane and out-of-plane stress accumulation and subsequent device failures by fragmentation in wet environments (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 | THIN self-supported to be manipulated on the spherical liquid droplet (left) and human skin (right) asymmetrically swollen and conformally self-adapted within a few seconds when hydrated.

Our work introduces several new findings. The simple yet effective method can achieve free-standing THIN with a thickness of 350 nm without any other complex and delicate handling processes that limit their practical use and compromise their intrinsic performance. The resultant THIN achieves microscopic conformability, which is among the lowest stiffness values reported for conductor nanomembranes, while maintaining superior mechanical and electrochemical properties and stability in wet and dynamic physiological environments. While we are truly excited about our THIN and its extraordinary properties, there are still remaining tasks to be done including better recording fidelity, compatibility to advanced micro-fabrication approaches for an increased number of recording channels and acquisition of spatial electrophysiological maps will be needed, for which we are actively working on to address in our upcoming studies.

We hope that our THIN can fill the technological void in free-standing conductor nanomembranes, and therefore, provide a useful material platform for next-generation bioelectronic devices and applications.

For more details, check out our paper “Hydrogel–elastomer-based conductive nanomembranes for soft bioelectronics” on Nature Nanotechnology.

This article is contributed by

Hyunjin Jung, Daeyeon Lee, BongSoo Kim, and Donghee Son

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Nanotechnology

An interdisciplinary journal that publishes papers of the highest quality and significance in all areas of nanoscience and nanotechnology.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in