In Knowledge we Trust: unpacking the language of persuasion in social media

Published in Social Sciences

Opinion formation in the public sphere

The “public sphere” theorized by Jürgen Habermas — one of the most influential philosophers of the Frankfurt school — is the public arena wherein the democratic discourse develops. It plays a crucial role in the healthy functioning of a democracy, as it allows citizens to shape public opinion. Collective participation in the public sphere peaked with the advent of the Internet and social media, whose collective dynamics weigh heavily on how public opinion evolves today. As the Social Web gets increasingly plagued by controversies, echo chambers, bots, and misinformation, it becomes crucial to discover and promote elements of social interaction that foster constructive dialog and cooperation.

In his theory of Communicative Action, Habermas sees shared understanding achieved through rational arguments as the necessary pre-condition for social integration, and thus for democracy. This process unfolds mainly through conversations; when language is used with the intent of promoting “shared knowledge, mutual trust, and accord with one another”, it can exert a powerful force that can change the hearer’s mind and bridge diverging views.

Quantifying social intent from language has been a hard challenge for computational linguists so far, and it remains an open research problem. Luckily, thanks to recent advances in machine learning, we are getting closer to the ability to automatically identify nuanced social intents from language. We used this ability to test some cornerstones of the theory of Communicative Action on social media data "in the wild". Read on to see what we found [tl;dr: Habermas was right].

Social dimensions of conversations

In ordinary social relationships, people often verbalize their social intent. We may say "don't worry, it's going to be ok" to provide emotional warmth in support of a friend, or "you have done such a wonderful job" to express our appreciation for them. Social scientists have studied several archetypes of social interactions, and in a previous study, we found that ten of them characterize the majority of ordinary human relationships (see Table below). We trained a deep-learning classifier that can label any message according to the social intent they convey, and successfully tested it on social media conversations. This tool allows one to answer at scale a question that stems directly from Habermas' theory:

"Which types of social intents are more effective at inducing a change of opinion in the listener?"

| Social intent | Description |

| Knowledge 📚 | Transferring information or ideas |

| Power 👑 | Exerting power over behavior of others |

| Status 🙏 | Conferring appreciation, gratitude, or admiration |

| Trust 🤞 | Expressing reliance on judgment of others |

| Support 🤗 | Providing emotional warmth or practical aid |

| Similarity 👯♂️ | Pointing out shared interests or opinions |

| Identity 🏳️🌈 | Declaring sense of belonging to a group |

| Fun 😂 | Experiencing leisure, laughter, joy |

| Romance 🌹 | Romantic exchanges |

| Conflict ⚔️ | Exposing contrasting or diverging views |

Social media to change your mind

To answer our question we turned to Reddit data, one of the favorite sources for social interaction studies conducted by computational social scientists all around the world. ChangeMyView is a subreddit where users can upload posts to express their own opinions, and other users comment on them in an attempt to change the opinion of the poster. Crucially, comments that succeed in doing so receive a token of merit called delta (Δ) from the poster. We gathered 46,000 posts about sociopolitical issues and their respective ~4M comments. We applied our social dimension classifier to all messages to label them with the social intents they express (if any). We then measured the association between social dimensions and opinion change.

Results

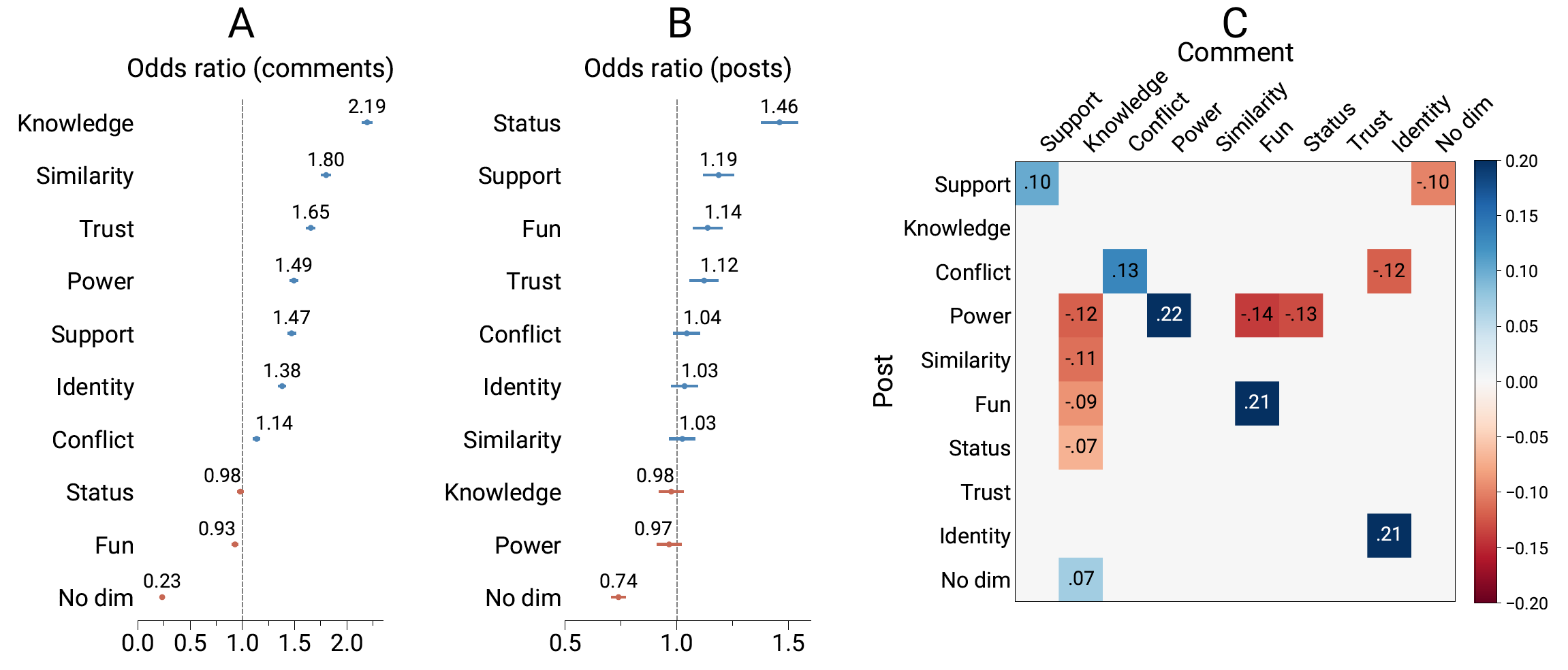

Figure A shows the odds ratios of different social dimensions being conveyed by comments that received a Δ, compared to comments with no Δ. For example, knowledge is 119% more likely to be found in comments with Δ (i.e., odds ratio of 2.19). Comments that express no intent are about 77% less likely to change the mind of the recipient, compared to comments that convey at least one social dimension. In line with the three pillars of Communicative Action (knowledge, accord, and trust), we found that opinion-changing comments are exceedingly more likely to convey factual knowledge and logical reasoning (e.g., “The NHS isn’t free, it’s free at the point of use, we pay for it through tax contributions”), allude at the similarity between the stance of the poster and the commenter (“My friends used to live in a large city in Asia too”), and contain language that expresses trust (“I believe what they’re saying”).

Interestingly, posts by people who end up changing their mind view are 46% more likely to convey status—words of appreciation, gratitude, or respect (“I have nothing but the utmost respect for service men and women, but ...”). On the contrary, people who introduce their opinion by appealing to power are the least likely to grant a Δ (Figure B).

Last, comments awarded with a Δ are more likely to express an intent that matches that of the original poster, at least for five of the social intents (Figure C). For example, when a post intends to convey a power dynamic, the most effective response is to make a similar appeal to power (+22% likelihood of getting a Δ). However, some pairs break this symmetry, such as power and status: giving appreciation in response to a comment characterized by power appeals is not a successful strategy of persuasion.

The new Glory of Social Media

The enthusiastic optimism that enveloped the rise of Social Media during the Web 2.0 revolution (remember? remember?) is now long forgotten, buried by armies of internet trolls, fake news, and endless partisan conflicts. Bringing online interactions forward to a renewed state of glory and value for society requires tools that can not only filter out bad behavior, but also that can encourage healthy practices. This work is a first step in this direction: we showed that computers can detect (and therefore promote) social interactions that foster understanding and ultimately agreement. Our future challenge is to use these technologies to realize Habermas' vision of an ideal arena of public discourse in which “all participants refer to facts and knowledge with which all are familiar, contribute to the discussion in an open, honest way, and be prepared to place themselves in the position of others in order to understand the latter’s point of view”.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Obesity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in