In science and in backlash, identities matter

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology and Philosophy & Religion

One of my favorite first science projects in grade school was comparing the life of different brands of AA batteries. I believe my affinity for science started then and continues to this day. Decades later, I am now a social psychologist who studies inequality. In my career, I have come to appreciate how multi-faceted science is, and importantly, how our experiences, perspective, and yes, even our identities, color and shape what we know, what we decide to study, and how we decide to study it. Diversity within science has never been particularly high, but it remains critically important.

In this political moment, anti-science and anti-diversity social forces are resurgent. They are resurgent in the halls of the US Congress, our neighborhoods, and within our academic institutions. These forces are transforming our institutions—they are also poised to further constrain who conducts science and how we will get to conduct it.

Some people are fine with these resurgent social forces, and truthfully, many will benefit (or already have benefitted) from diversity backlash. Others ignore them because they have, in my estimate, a narrow and incorrect view of science and diversity—one that envisions scientists as separate, politically neutral, dispassionate, and objective observers of facts in the world, and science as a practice where identities shouldn’t matter.

Science can never be, nor has it ever been, dispassionate and objective. Science projects start from research questions that are driven by people’s interests and informed by experiences. Producing science is also costly, and so the scientist must navigate a research question along with a funding body, or perhaps along with an organization, who might have a particular stake in the answer. Science also tends to be about people in the world, with the answers to questions posed by scientists mattering a great deal for people’s lives. How one could presume to be dispassionate and objective in this context, stretches the bounds of one’s imagination.

And yet, people in science claim versions of objectivity all the time. Often these claims occur in the context of evaluating science conducted by scholars on the margins of a discipline. Though all scientists must contend with how their past experience and perspective shapes the research process, it is racially marginalized scholars conducting research on their marginalization where identity is salient (and potentially threatening) to primarily white academic audiences. My former student Brittany Torrez, PhD studied this through a mixed-method interview study of racially marginalized scholars.

The study itself started as an examination of racially marginalized scholars’ experiences giving talks in front of primarily white scientific audiences. In the interviews, scholars described their experiences during talks that were about race and racism (and those that were not as a kind of control experience). The interviews were conducted with white and racially marginalized scholars to examine racial differences in experiences, and all career phases were included. Overall, the interviews involved 36 hours and 51 scholars.

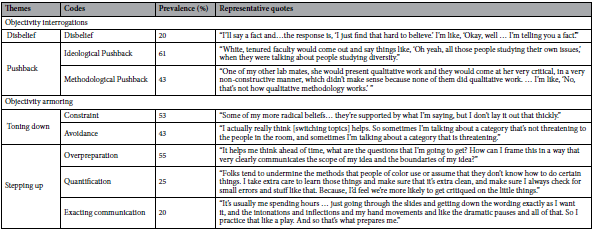

Dr. Torrez’s interviews revealed widespread experiences of interrogation of the objectivity of racially marginalized scholars conducting research on race and racism. That is, 87% of racially marginalized scholars had their expertise, methodology, bias, or competence directly questioned at least once during a research presentation on race and racism. Sometimes these interrogations questioned the methodological choices and decisions of racially marginalized scholars (43% of scholars), other times these scholars were accused of bias (61%), and other times audience members denied basic facts as they were described in the talk (20%).

Now, science talks often involve criticism, but there were indications throughout the interviews that these interrogations of objectivity were particularly likely to occur in the context of racially marginalized scholars talking about race and racism. Similar interrogations of objectivity were much less common among white scholars when talking about race and racism. They were also less common for racially marginalized scholars giving non-race relevant talks (e.g., on motivation science). Importantly, objectivity interrogations had the added drawback of crowding out legitimate feedback about the research projects for racially marginalized scholars—instead of considering questions that could advance the research, racially marginalized scholars had to navigate comments that questioned their expertise, intelligence, or that the basic facts of the data were true or real.

What were the impacts of these objectivity interrogations? One primary impact was that many (55%) racially marginalized scholars contended with the additional scrutiny through extra and intensive preparation for talks on race and racism. Still others (43%) avoided discussing scholarship that triggered these interrogations. Sometimes avoidance meant seeking out speaking opportunities and research questions where race and racism were not central topics. For others it meant sometimes forgoing talks attached to opportunities for employment or prestige so that they could avoid the comments that questioned their integrity or lived experiences.

I invite all scientists to read the paper and examine the experiences of racially marginalized scholars in their own words. My hope is that these interviews help other scientists see that, when we cling to reductive notions of scientists as dispassionate and objective observers of facts in the world, we grossly misrepresent what it is we are doing. Science, as it turns out, is many things and contains many epistemological standpoints, experiences, and perspectives. Science, however, is not a view from nowhere. We do not call proverbial balls and strikes for the known universe through science. Instead we interpret, theorize, reason, and get things right and wrong about the order of things through observation, description, experimentation, and tinkering. At each point in the process of science, all of us have experiences and identities that shape what we know and how we study it. Certainly, anti-science and anti-diversity motivations come from experiences and identities too.

I also invite all scientists who value diversity to think about how, what marginalized scholars experienced in our study, is likely to intensify in this resurgent anti-science and anti-diversity movement. As this movement surges, we will all need to be active and engaged counterweights in the next department meeting, class session, and at the next conference.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Women’s Health

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in