Investigating the heart of science policy

Published in Social Sciences

To what extent and in what way do the needs for scientific knowledge in health expressed by different stakeholders translate into research funding priorities and research portfolios useful for solving problems that affect these actors?

This is the research question that I am really passionate about and that I want to work on in the coming years.

To explain the complexity and importance of the research question, I ask the reader to join me in a mental role-playing exercise. Think of yourself as a person who is affected by one of the great problems facing society. Perhaps you are a US citizen whose family member has lost their life due to a medication contaminated with fentanyl and you are concerned about the increase in the number of deaths related to this substance. Maybe you are a cancer patient whose medical treatments are unaffordable or are not working well enough, and you participate in an organization that defends your interests and your rights as a patient. As a citizen who has experiential knowledge about the opioid epidemic in the United States or the emergence of complex diseases pandemics such as cancer, your expertise is highly valuable for the design of science and technology policies. Imagine now that you, along with others affected by these problems, are consulted by a government agency or a philanthropic foundation interested in using your non-academic expertise in the formulation of science and technology policies. Some of you will be surveyed, others interviewed, and still others will participate in focus groups. After being consulted, back home, you may wonder if it was worth the time invested in the consultation exercise and, above all, if your opinion will really be taken into account. Your doubts about whether you were really heard, as you represent a group of affected people with something important to say, are totally legitimate. Probably, representatives of the various sectors of society and the research funding agency itself also wonder to what extent their sectoral and organizational interests and objectives will be reflected in research funding policies. Hence, the first specific objective of my research can be stated as follows:

To understand how the demands of the actors are translated and articulated in the research priorities, calls and criteria for the evaluation and selection of health research projects.

Let us assume that the consultation process was successful and the concerns, interests and knowledge of the various stakeholders are clearly reflected in the research funding priorities. Now put yourself in the shoes of a researcher interested in applying to one of the calls for funding research that is oriented toward solving problems of social relevance. Perhaps you are a researcher specialized in the biomolecular mechanisms involved in the development of cervical cancer or perhaps you are an expert in the design of health policies aimed at harm reduction. The point is that you have a set of knowledge and skills acquired throughout your academic training and you also have a projection of what you want to do in the future as a researcher. Not only that, in your hiring process, in the construction of your collaboration networks, in the acquisition of research infrastructure, and even in your participation in scientific societies you have acquired a set of institutional and organizational commitments that impact your research. When reviewing the call, you will find interesting points that align well with your profile and research interests and you will find other points that are far from your academic interests and even requirements that are difficult to meet or even understand. The project you propose is necessarily the product of a compromise between your interests, knowledge and skills, the objectives of your institution, the values of the academic community to which you belong, and the requirements of the call. The project you proposed will most likely be evaluated by a panel of independent experts at the request of the funding agency. Although the evaluators were previously instructed on the evaluation and selection criteria of the projects, they come to the panels with a specific academic training and with their own vision of the world. It may be that in addition to scientific experts, representatives of stakeholders participate in the project evaluation and selection process. Regardless of how the selection of projects is organized, it will necessarily be the product of a compromise between the rules of the calls, the knowledge, experiences and vision of the expert evaluators and other actors who participate in the process. If your project was selected you will have made a commitment to deliver a set of specific deliverables, including articles published in peer-reviewed journals, patents or policy documents. However, the research process is neither linear nor completely controllable. You may, for example, be lucky enough to make an unexpected discovery of scientific relevance that is unrelated to the research objectives of your project. The publication process is also not under your control, since scientific journals have their own editorial criteria, and editors and reviewers could suggest substantive changes to your research. Taking all of the above into account, my second research objective can be formulated as follows:

To analyse to what extent the description of research projects research and the content of academic publications correspond to the demands for scientific knowledge of the actors consulted.

The process of generating useful and relevant knowledge to solve society's urgent problems does not end with the publication of articles or the granting of patents, knowledge has to be well used by society, particularly by those stakeholders who experience firsthand the reality of environmental, social and health problems. Of course, it is not the case that all citizens can understand the details of a sophisticated article published in a specialized journal. What it is about is the correct articulation between the scientific knowledge produced and the decision-making process, translated into public policies, clinical practices or organizational strategies.

Hence, my third research objective can be formulated as follows:

To determinate which actors use the scientific knowledge generated and analyse how they use it to inform policies and clinical practices and strategies to address health problems.

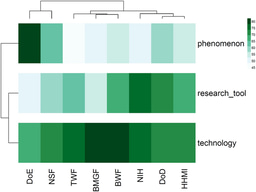

An ambitious project titled "NECESSARIES: The translation of the scientific knowledge needs of stakeholders into relevant and usable health research portfolios" is articulated around these three research objectives. In the project I propose to satisfy the research objectives through the use of qualitative methods such as the analysis of institutional documentation, interviews with experts and focus groups with interested parties, in combination with the quantitative analysis of information on the funded research projects and their publications, as well as the analysing the social use of this knowledge in social networks, media, policy documents, clinical guides, among others.

The project was submitted to the MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2023 call and was approved by the reviewers receiving excellent comments regarding its strengths. However, it did not reach the necessary score to be funded by the European Commission. I don't give up. My plan is to improve it and make it known to society and research funding agencies who may be interested in new ways to evaluate and improve the social impact of their research portfolios. The project is published in Zenodo, and I invite you to read it and think about possibilities of collaboration with me and with the team of researchers from INGENIO-SCIC and CWTS-Leiden who participated in the proposal.

I share with you some of the observations made by the panel of expert reviewers:

-The relevance of the research and innovation objectives is very good, being scientifically and societally relevant in examining how scientific knowledge in the health domain is produced and used, and the role of different stakeholders in this process.

- The research questions and objectives are reasonably precise, and in this sense they are measurable and achievable.

- In general, the methodology is convincingly described with much detail and comprises a sequence of logical and well-considered research processes, both qualitative and quantitative.

- The highly ambitious research is truly interdisciplinary, and justifies well the need for, and integration of, disciplines including scientometrics, research policy, informatics, and clinical/biomedical sciences.

- The gender dimension is very good, as intersectional forms of discrimination and epistemic injustice are recognised as significant. Suitable measures are taken to ensure gender and other diversity aspects are acknowledged and accounted for.

- Open science practices are fully aligned with current best practice guidelines and exemplary in their extent and expected reach.

- The proposed AI deployment consists of using Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools for analysing information retrieved from research databases. Since no personal data will be processed, it is technically robust.

- The researcher will be guided by an excellent and outstanding supervisory team that matches the proposal very well. The supervisory team has an excellent a track record and is sufficiently experienced in supervising researchers.

- The variety and quality of training opportunities are excellent, especially with regards to scientific processes.

- The rationale of the non-academic placement is very well justified. Its added value for the proposed work is appropriate and significantly enhances the quality, scope and expected reach of the proposal.

I would love to read your opinion, questions and suggestions in the comment section below and it would be great if you read the proposal.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in