It is time for a global ban of declaw in cats

Published in Social Sciences and Biomedical Research

As someone passionate about animal welfare, I couldn’t understand why cat owners would request it. Declawing struck me as deeply unnatural, a mutilation rather than a treatment. I still remember reading a letter to the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association in 2006, where Dr. Michael W. Fox, an expert in animal behavior, wrote:

“Caring and responsible cat owners effectively train their cats to use scratch-posts… rather than resort to routine declawing, which amounts to a mutilation for convenience.”

Yet, the response from other veterinarians dismissed this view, claiming the pain was “trivial” compared to other procedures. The reasoning was essentially utilitarian: if it prevents owners from abandoning their cats, then declawing is justified. And so, the practice remained widespread across the United States and even parts of Canada. In fact, by 2025, it is estimated that some 25 million cats in North America will have been declawed.

Declawing is not simply trimming nails. It is the amputation of the last bone of each toe, usually on the front paws, sometimes on all four. It can be done with a scalpel, surgical laser, or even sterilized nail clippers. Research has compared techniques, pain protocols, and complications, but the dominant narrative always returned to the same idea: declawing is controversial, but still saves pets.

Even the American Veterinary Medical Association concluded in 2022 that “conflicting scientific evidence exists regarding the implications of declawing.” As a scientist, I knew this “conflict” was really a gap in the research: there had never been a rigorous, long-term study of the chronic pain caused by declawing.

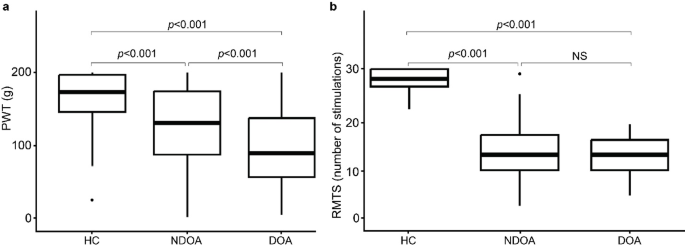

That became my motivation. With colleagues at the Groupe de recherche en pharmacologie animale du Québec (GREPAQ – Université de Montréal), we had unique access to a colony of cats living with natural osteoarthritis, a common and painful condition of aging animals. Therefore, we were able to get access to 24 healthy cats, 125 non-declawed osteoarthritic cats and 39 declawed and osteoarthritic cats, all assessed through the same outcomes. Supported by Canadian research funding[1], we developed specialized tools to measure pain and nerve function in cats — from veterinary clinical tests to gait analysis, brain imaging, and nerve conduction studies. This included in the present study:

- Functional alterations through the Montreal Instrument for Cat Arthritis Testing, for use by Veterinarians, MI-CAT(V)©;

- Neurophysiological alterations through Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST) which determines peripheral and central neuro-sensitization, confirmed by neuro-imaging (PET-scan, MRI), as well as electrodiagnosis (nervous conduction, EEG);

- Biomechanical alterations through a performing podobarometric gait analysis, recognized as the gold standard for assessing lameness in quadrupeds.

This allowed us to separate the pain caused by osteoarthritis from the additional suffering caused by declawing. What we found was striking: declawing leads to aggravated long-term nerve damage, heightened sensitivity to pain, and worsened mobility issues, especially in heavier cats. The nervous system, overloaded from a young age, eventually becomes exhausted, leading to chronic fatigue, hypersensitivity, and reduced well-being.

In other words: declawing does not simply remove claws. It sets cats on a lifelong path of pain.

As veterinarians, our mission is to protect animal welfare. By continuing to perform declawing, we have failed that mission. The evidence is now clear: this is not a routine surgery but an ethically unacceptable practice with serious and lasting consequences. It is time for a worldwide ban on declawing.

[1] Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Canada Foundation for Innovation.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Women’s Health

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in