Janusian governance: on moving when the new stands still

Published in Social Sciences, Law, Politics & International Studies, and Philosophy & Religion

I. The Evening After, and the Two-Faced Gaze

It began with a walk in Brasília and a conversation with my friend Larissa Spinola. We were not speaking in abstractions; we were trading impressions of Lula’s first years after Bolsonaro, testing words against what we were seeing and hearing. We had expected the emblematic public choreography of the new: fresh programs, brand-new acronyms, the reassuring grammar of rupture. Yet what kept returning to the surface was quieter and more stubborn: rooms reopening; councils reconvening; benefits and routines being re-anchored so that people might trust the floor again. It felt less like a parade of novelty than like someone opening windows in a house that had been shut too long.

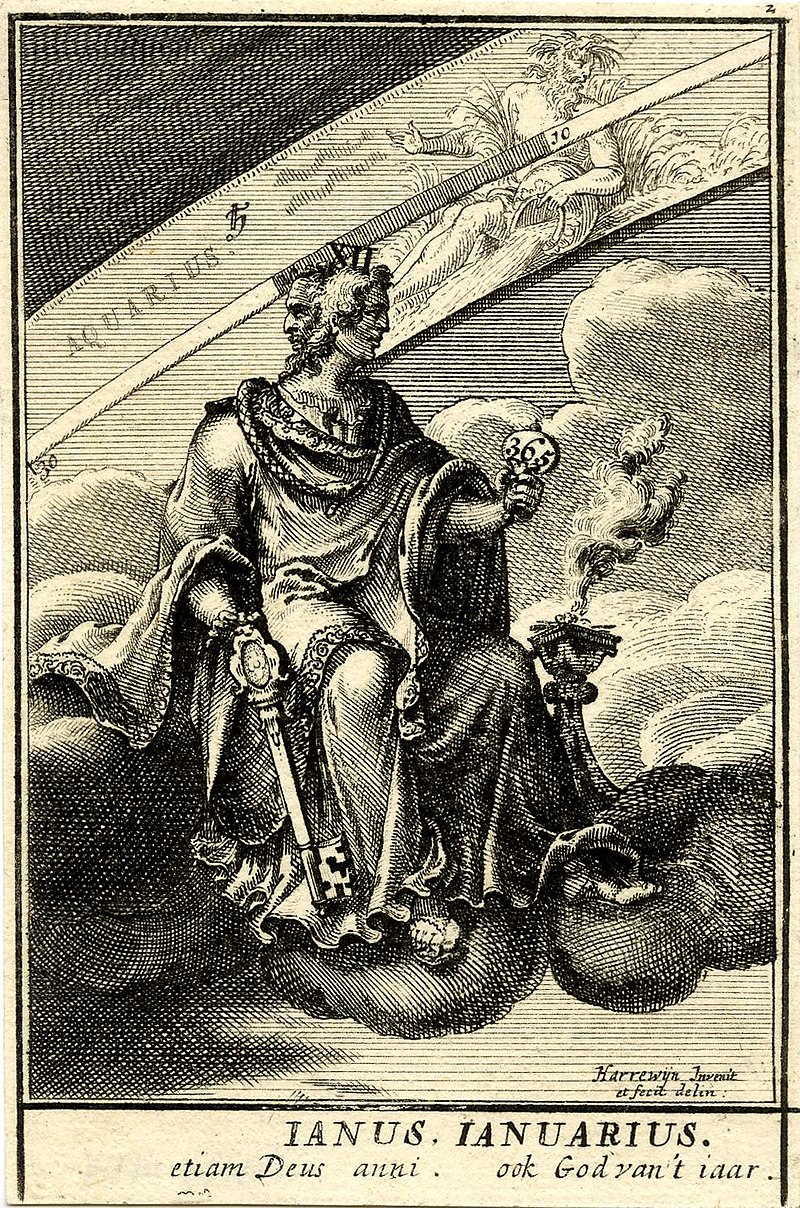

On the way home, a figure appeared and stayed: Janus, the Roman with two faces, not the emblem of indecision but the discipline of looking backward and forward at once. The image clarified a rhythm I had felt but had not named. We were watching practices of restoration (repairing institutions, reviving guarantees) entangled with practices of invention (designing tools, categories, and oversight) that had no exact precedent. The point, I began to think, was neither to celebrate the past nor to worship the new, but to learn the craft of pairing them so that each limits the other’s excess and frees the other’s promise. The paper calls this craft Janusian governance: not a compromise, but a counterpoint; two lines held together so the composition moves.

II. The Stillness Inside Motion

If Janus lent double vision, another figure warned about a trap that stalks modern governance. Walter Benjamin’s Angel looks upon wreckage piling at his feet even as a storm called progress blows him into the future; propelled, yet unable to repair. It is an unsettling portrait because the feeling is familiar: dashboards that become the argument itself; pilots that never ripen into decisions; an administrative rhetoric of agility under which institutions grow curiously inert. Innovation, stripped of its companion, begins to freeze. We mistake motion on screens for movement in the world; the storm that calls itself progress pins our capacity to act. Under late capitalism, public administration inhabits precisely this tension: it must manoeuvre like Janus even as it is buffeted like Benjamin’s Angel.

Brazil taught through scenes, not slogans. One was the reopening of participatory councils. Just convening was a relief. The room breathed again and our deliberative voice returned. Yet reinstatement is not the same as consequence. When agendas remain upstream, evidence arrives late, or budgets are already locked, deliberation risks becoming choreography: everyone is heard, minutes are filed, decisions are made elsewhere. The answer is not to abandon councils but to rework the procedural plumbing so that council deliberation has binding force, aligning timing, agenda, and authority. The act is restorative in spirit and inventive in execution: two faces, one hinge.

Another scene, briefer still, sits in the ride-hailing world that so many of us inhabit as passengers: PLP 12/2024, the draft bill proposing a minimum remuneration per hour, caps on daily connection hours, and shared social-security contributions for platform drivers. On its surface, the gesture is recognizably restorative. Ordinary labor guarantees returning to a market that had declared itself post-labor. But making those guarantees real presumes new administrative capacities: auditable platforms, traceable data flows, oversight that can look an algorithm in the eye. If rights dominate without instruments, they remain a speech act; if instruments dominate without rights, they dissolve into technical theatre. The bill looks both ways at once, and its truth lies in the pair.

These scenes sharpen the claim: innovation is not the hero by default. There is a porcelain version of novelty (impressive, fragile, cold to the touch) that paralyzes. It appears when numbers displace reasons; when automated eligibility denies at scale with thin avenues for appeal; when “hybrid” legal categories promise flexibility yet keep workers in limbo. The antidote is not more novelty, but companionship: restoration that lends legitimacy and care; invention that lends reach and capacity. There, movement begins.

III. A Practice, Not a Doctrine

From that evening with Larissa, the paper took shape as an effort to say something plainly in a philosophical key: after a corrosive cycle, Brazil’s governance did not spring from a void; it proceeded by re-stitching public capacities and composing them with new instruments so they could survive the weather. This is not nostalgia. A restored program that cannot be audited may soothe, but it will not stand. A gleaming tool untethered from a public claim may dazzle, but it will not care. Janusian governance asks us to bind them (repair with invention, invent with care) not as a taste for the middle but as an ethics of action under constraint.

The ethics matters because late-capitalist turbulence supplies headwinds, not clean horizons. Hybridity is not a failure of will; it is often the condition for doing anything at all. Modernist managerial logics persist (hierarchy, standardisation, metrics) even as late-capitalist contradictions demand improvisation and oversight that the old repertoire cannot supply. To treat this as pathology is to miss the point. The oscillation itself, moving between hope and audit and between forward reach and backward guardrail, can be the engine of progress when grand narratives have thinned. Programmes launched in sincerity, inspected in irony, revised in sincerity again: the cadence is humbler than rupture and braver than return.

The Brazilian threads keep the thought honest. When councils reopen, their dignity is not only symbolic; it is institutional memory insisting on consequence. When a platform bill promises a wage floor, its plausibility is not only legal; it is administrative imagination insisting on instruments that make the promise visible in a payslip and enforceable in practice. Even the familiar architecture of a cash transfer (think of the reflex to restore what worked) carries this double life: it can both shield households and reinscribe managerial gatekeeping, unless the apparatus that counts learns to be accountable (legible to citizens, contestable by design). The discipline is always the same: let each face veto the other’s worst impulse. Without the restorative guardrail, invention grows brittle and remote. Without the inventive hinge, restoration congeals into rite.

What remains, then, is a modest invitation rather than a grand doctrine. In any room where the future leans hard (new app, new framework, new reform) ask aloud what must be restored so that the novelty means what it claims. In any room where the past leans hard (bring back the council, revive the program) ask what must be invented so that the return is more than symbol. Tie the answers together. The knots are not glamorous. Small hinges on which larger futures swing.

I return, finally, to that evening with my friend because it grounds the argument in ordinary time: buses and bills, rooms airing out, people measuring words against facts. Janus’s lesson is not an aesthetic; it is a practice. Keep both faces in view. Move because they are held together. And whenever the storm called progress pins your feet, remember the other figure in the paper (the immobilised angel) so you can turn his gaze into Janus’s stride, not by force of will alone, but by composition: the kind that lets a polity act without being captured by its own instruments.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Global Society

This is an interdisciplinary, international journal that welcomes research on the complexities of modern global society, its development and its challenges.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Social Policy and Indigenous Rights: Reclaiming Sovereignty, Identity and Social Justice

Indigenous communities worldwide have long faced systemic injustices, including land dispossession, cultural suppression, and socio-economic marginalization. Social policies play a critical role in addressing these historical wrongs and advancing Indigenous self-determination This special issue explores how reparative justice, decolonizing practices, and progressive policy frameworks can contribute to reclaiming Indigenous sovereignty, preserving cultural identity, land rights and ensuring justice for Indigenous peoples. The relationship between sovereignty, identity and justice is central to Indigenous worldviews, yet colonial legacies continue to undermine Indigenous sovereignty. Effective social policies must go beyond symbolic recognition to enact substantive changes that empower Indigenous communities. This issue highlights theoretical research, empirical perspectives, case studies, policy analyses from Indigenous perspectives that examine how legal frameworks, governance reforms and community-led initiatives contribute to sustainable, equitable futures. By fostering a dialogue on Indigenous rights, social welfare policies, this collection aims to illuminate pathways toward justice, resilience and self-determined development for Indigenous peoples worldwide.

Keywords:Indigenous Rights; Social Policy; Land Reclamation; Reparative Justice; Decolonization; Self-Determination; Cultural Preservation; Equity and Inclusion; Indigenous Governance

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Gender, Environment, and Sustainability: Bridging Gaps and Building Future

The pressing challenges of environmental degradation and climate change demand innovative solutions that are sustainable, inclusive, and equitable. Gender, as a critical dimension of social structure, shapes the vulnerabilities, experiences, and responses of communities worldwide facing environmental risks. Women play diverse and pivotal roles as leaders, decision-makers, resource managers, activists, and scientists in addressing ecological issues; yet, they continue to face barriers to access, participation, and recognition within environmental sectors.

This collection, "Gender, Environment, and Sustainability: Bridging Gaps and Building Future," explores the intersection of gender and the environment as a transformative lens for achieving sustainability and social justice. The collection welcomes contributions that examine how gender-based disparities influence environmental outcomes, how women’s empowerment enhances ecological stewardship, and how Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can be advanced through gender-inclusive policies and practices. Submissions may cover topics such as gendered impacts of climate change, women’s leadership in environmental governance, gender mainstreaming in sustainability science, and case studies from diverse social, cultural, and geographical contexts.

By bringing together global perspectives, empirical analyses, and practical frameworks, this topical collection aims to foster rigorous research and constructive dialogue on the shared journey toward a more sustainable and equitable future for both genders. Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers from diverse backgrounds are invited to contribute their insights and innovations to bridge the gaps and build resilient pathways for future generations.

Keywords:Climate Action, Women’s Empowerment, Gender Equality, Reduced Inequalities, Environmental Sustainability, Quality Education

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Aug 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in