Large numbers of patients are needed to obtain additional approvals for new cancer drugs

Published in Biomedical Research

Drug development is expensive and failure-prone. According to recent estimates, drug companies must invest $2.6B to bring a new drug to market 1. Many commentators defend high prices on drugs by appealing to the expense and risk of developing new drugs.

However, drug companies aren’t the only entities that bear risk in drug development. Patients, too, endure risks when they volunteer to participate in drug-testing clinical trials. A recent study from our lab (STREAM, or Studies of Translation, Ethics and Medicine) showed that it takes about 12,000 patients to develop a new cancer drug; 40,000 for a new high-impact cancer drug 2. In other areas, like neurological drug development, the number of patients needed to develop an effective drug is similar 3. Most of these patients will have to make extra clinic visits, endure extra blood draws, and receive an experimental (or comparator) intervention.

If you are a private drug developer, you are likely to be looking for methods that allow you to develop a drug with less financial investment. As ethicists, we are interested in the moral complement to this problem: how can we develop drugs with less commitment of patient welfare? One strategy that might enable this is drug repurposing (i.e. redirecting an approved drug towards a totally new indication) or label extension (i.e. finding applications for an approved drug in a new but related indication). In cancer, the latter is common. Almost a third of cancer clinical trials aim at extending the label of already approved drugs 4.

One might expect label extension to require fewer patients than novel drug development. This reflects that, at the point where such efforts are initiated, sponsors already understand the safety profile of the drug and its dosing. They also know the drug engages its target and has anti-cancer activity. The only step that is required to get a new approval for an already approved drug is to prove that it works for a different patient population than the one for which it is approved.

In this research project, we set out to determine if, in fact, extending the label of an already approved cancer drug required fewer patient participants than developing a cancer drug completely from scratch.

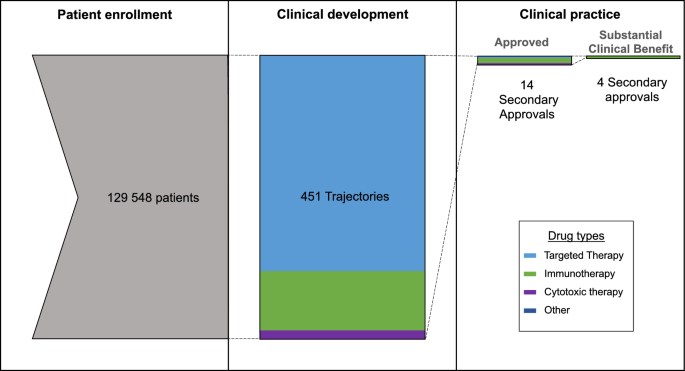

To do this, we identified all the anti-cancer drugs that were approved by the FDA between 2012 and 2015. Then we looked at all the clinical trials involving these drugs that started after the initial approval. We organized all the clinical trials into research trajectories (a series of clinical trials testing the same drug in the same disease) and counted the number of trajectories that ended with another FDA approval for the drug in question. We also counted the number of research trajectories that resulted in an off-label recommendation in clinical practice guidelines (NCCN guidelines), and we worked with a clinical oncologist- Joseph Del Paggio- to count the number of trajectories that resulted in an FDA approval that was deemed to provide “substantial clinical impact” to patients (based on the European Society of Medical Oncology, Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS)).

We identified 42 anti-cancer drugs approved by the FDA between 2012 and 2015. A total of 451 research trajectories were started for these drugs following their approval, enrolling close to 130 000 patients in total. Fourteen of these research trajectories led to another FDA approval. That means that close to 10 000 patients were needed to extend the label of an already FDA-approved drug – a quantity that is similar to the 12 000 needed to develop a totally new cancer drug. Around 5000 patients were needed to obtain an off-label recommendation in NCCN guidelines, and 32 000 patients were needed to get a secondary approval deemed to provide significant clinical benefit to patients. What our study revealed is that the advantages of having matured safety and pharmacology knowledge on an approved drug do not translate into reducing the number of patients needed to discover new treatments.

Since this study was patient-focused, we worked with Carol Matyka, a patient advocate from the CARE Advocates Network, to refine our measures for this project. Ms. Matyka urged us to also measure the number of patients needed to extend the label of a cancer drug based on evidence of improved quality of life. Here too, the figure was 32 000 patients.

A previous study from our lab suggested that label extensions for cancer drugs are generally less impactful than first approvals. 5 Together with the present findings, our study highlights that label extension is no shortcut for improving the per-patient impact of clinical trials. In fact, taken together with our previous findings, label extension research may be a less efficient way to apply patient welfare to medical progress. Above all, our findings underscore that large numbers of patients bear risk for drug discovery.

References

1 DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G. & Hansen, R. W. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of R&D costs. Journal of health economics 47, 20-33 (2016).

2 Hutchinson, N. et al. Patient Participation in Clinical Trials of Oncology Drugs and Biologics Preceding Approval by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA network open 4, e2110456-e2110456 (2021).

3 MacPherson, A. et al. Quantifying patient investment in novel neurological drug development. Neurotherapeutics 19, 1507-1513 (2022).

4 Gumnit, E. et al. The proportion of North American cancer trials that evaluate novel targets. Investigational New Drugs, 1-4 (2020).

5 Ouimet, C., Bouche, G. & Kimmelman, J. Diminishing clinical impact for post-approval cancer clinical trials: A retrospective cohort study. Plos one 17, e0274115 (2022).

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Women’s Health

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in