Learning during the pandemic in Uzbekistan

Published in Sustainability and Education

Learning Loss During COVID-19

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced schools around the world to close, educators and researchers feared the worst: that learning would stall or even regress, especially for the most vulnerable students. In many countries, those fears were confirmed, with evidence of significant learning loss in foundational subjects like mathematics [1,2,3].

Analyzing Learning Outcomes over Time

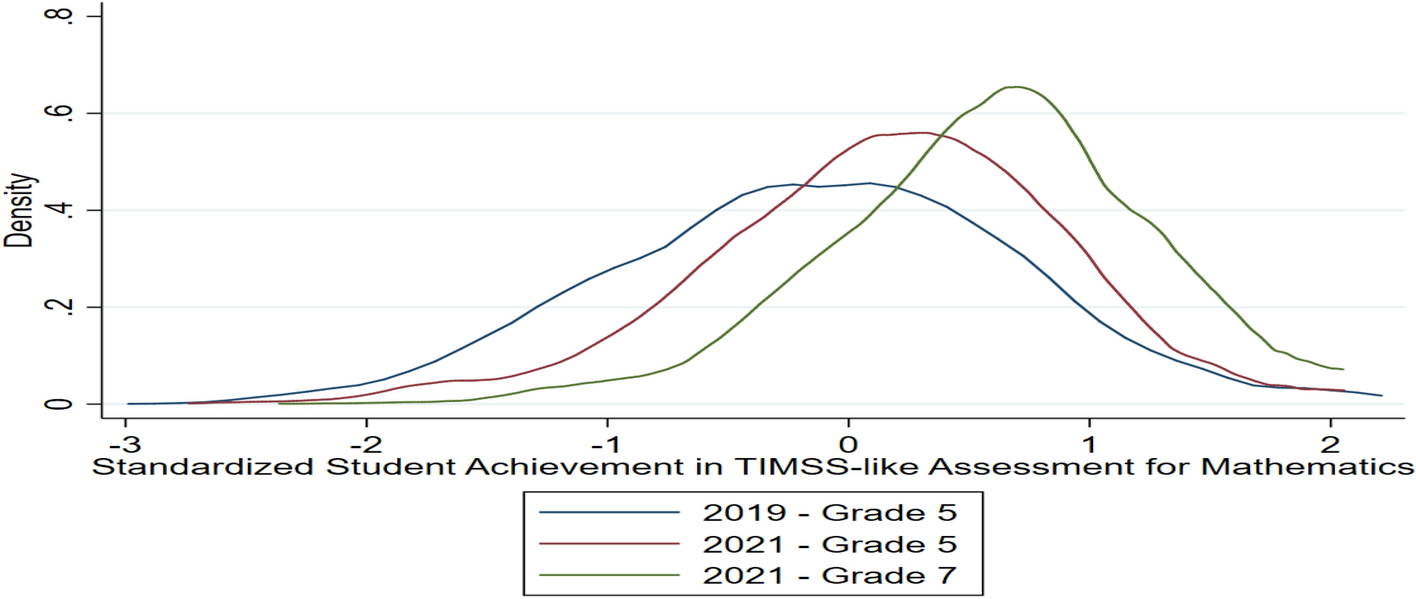

Our study (with Syedah Aroob Iqbal) analyzed nationally representative, IRT-scaled data on mathematics achievement for grade 5 students before and after the pandemic. In 2019, a cohort of students was assessed; in 2021, students from the same schools—including 87% of the original cohort—were reassessed with a comparable test and accompanied by student and teacher questionnaires. Contrary to global trends, math scores improved. Students assessed in 2021 outperformed those tested in 2019 by 0.29 standard deviations, and students tracked over time showed an average gain of 0.72 SD over two years.

Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Public Education acted quickly. From March 31 to May 25, 2020, the Republican Education Center created and broadcast 4,492 video lessons across four state-owned TV channels in Uzbek, Russian, and Karakalpak, covering all core subjects for grades 1–11. These lessons aired daily, with schedules announced in advance, and were also accessible via online education portals and Telegram channels, which attracted millions of daily views. Highly qualified teachers were selected to deliver these televised lessons—enhancing instructional quality even in remote settings [4].

Back in 2020, as lockdowns began, I hoped that well-designed distance education could mitigate the crisis. Uzbekistan’s experience shows that with strong planning and public commitment, learning continuity is possible—even under duress [5].

Uzbek children were out of the classroom for more than 4 months on average, a very long period of school closures due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In-person teaching has many benefits, but the good news is that students did not face learning losses in math due to the school closures. In fact, Uzbekistan is one of the few countries that experienced the opposite trend during the pandemic.

A Note of Caution

Yet, the story isn’t uniformly positive. As in other countries [6,7,8], we observed inequities in learning outcomes. Students with less-educated parents or teachers lacking strong pedagogical skills gained significantly less than their peers. While we found no statistically significant effects related to the length of school closures, there were hints that longer closures may have had a negative effect on learning. Notably, children of more-educated parents saw substantially larger improvements in scores than those with less-educated parents—underscoring persistent equity concerns.

Still, the broader message is encouraging. Uzbekistan is one of the few countries where learning improved during the pandemic, thanks to policy decisions that prioritized continuity. These findings suggest that proactive investment in assessments, teacher training, and accessible content delivery platforms—including low-tech solutions like TV—can help education systems withstand and even thrive during crises.

Looking Ahead

Looking forward, Uzbekistan’s experience offers a platform to build on [9]. National scores remain below international benchmarks, but the rapid development of online infrastructure and data systems provides tools to improve quality and equity. The next step is rigorous impact evaluation of the various initiatives launched during the pandemic—so that we can better understand what worked, for whom, and why.

This experience should inspire not just reflection, but action—both in Uzbekistan and in other countries searching for ways to build more resilient education systems.

References

- Agostinelli, F., Doepke, M., Sorrenti, G., & Zilibotti, F. (2022). When the great equalizer shut down: Schools, peers, and parents in pandemic times. Journal of Public Economics,206, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104574.

- Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Geven, K., & Iqbal, S. A. (2021). Simulating the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: A set of global estimates. World Bank Research Observer,36(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkab003.

- Psacharopoulos, G., Collis, V., Patrinos, H. A., & Vegas, E. (2021). The COVID-19 cost of school closures in earnings and income across the world. Comparative Education Review,65(2), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1086/713540.

- Meliboeva, N., Patrinos, H.A., Teixeira, J., 2020, Uzbekistan: A timely response on learning during school closures, World Bank Eurasian Perspectives blog, https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/europeandcentralasia/uzbekistan-timely-response-learning-during-school-closures

- World Bank. (2020, April 28). WB expert on Uzbekistan's response to the learning challenges during the lockdown [Video]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=329458284686492

- Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, D. M. (2021). Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,118(17), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118.

- Lichand, G., Doria, C. A., Leal-Neto, O., & Cossi Fernandes, J. P. (2022). The impacts of remote learning in secondary education during the pandemic in Brazil. Nature Human Behavior,6(8), 1079–1086. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01350-6.

- Clark, A. E., Nong, H., Zhu, H., & Zhu, R. (2021). Compensating for academic loss: Online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Economic Review, 68, 101629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101629.

- Das, J., & Zajonc, T. (2010). India shining and Bharat drowning: Comparing two Indian states to the worldwide distribution in mathematics achievement. Journal of Development Economics, 92(2), 175–187.

Follow the Topic

-

PROSPECTS

Prospects is a leading journal providing comparative and international perspectives on current issues in curriculum, learning, and assessment.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in