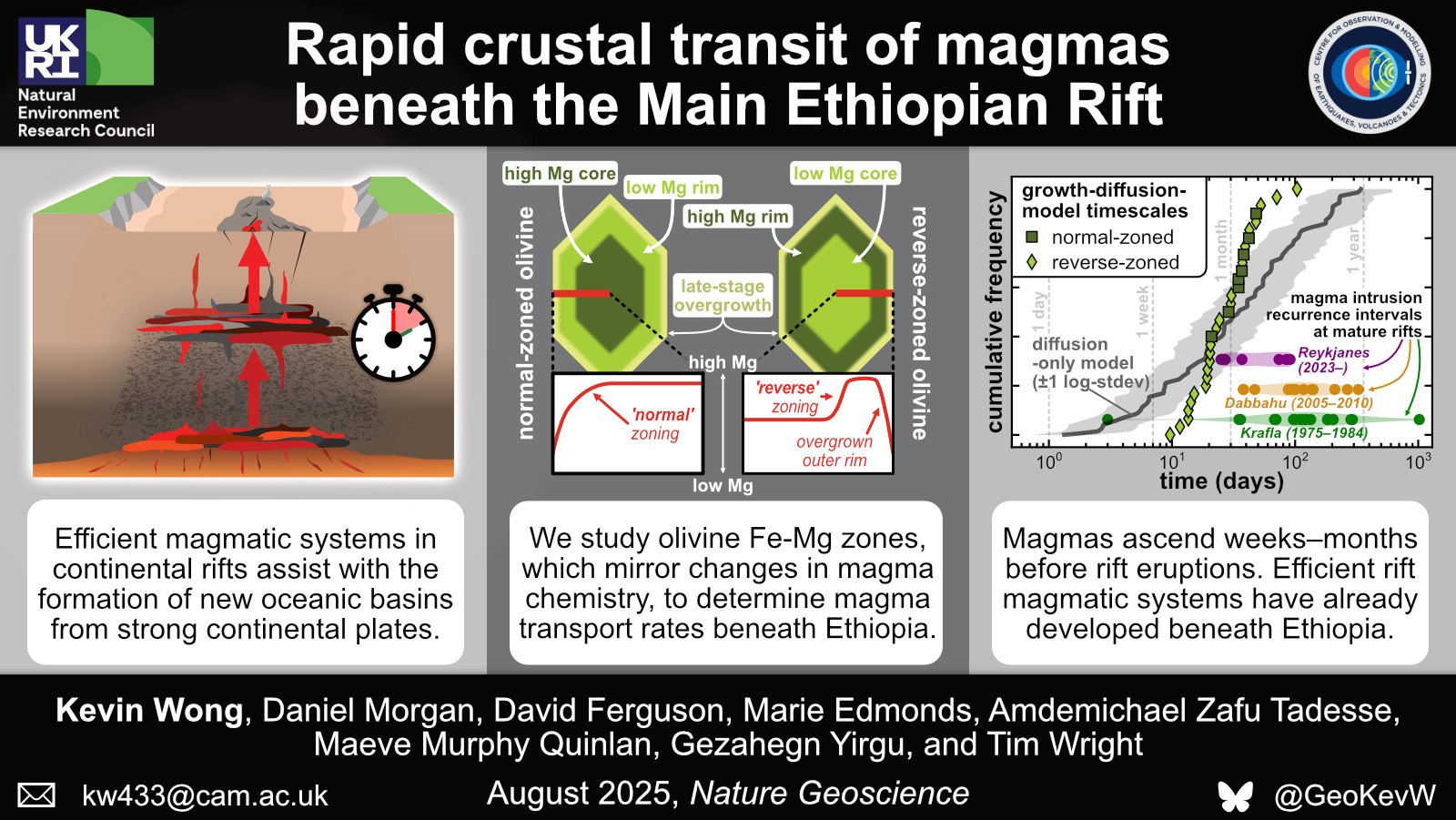

Magmas move rapidly beneath Ethiopia

Published in Earth & Environment

Continental rifting is the tectonic process by which continents are ripped apart to form new ocean basins, moulding the Earth’s surface environment. The nature of continental rifts changes as they mature; while young rift systems extend by tectonic faulting, late-stage rifts are driven apart by the injection of hot magmas that thermally weaken the crust. Magmatic activity therefore accelerates a rift's evolution towards complete rupture [1], and late-stage rift zones are sites of intense seismic and volcanic activity, as showcased during recent rifting episodes in Afar, Ethiopia (2005–2010) [2] and the Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland (2023–present).

The transition of continental rifts into oceanic spreading centres remains a key topic in geodynamics, with important implications for Earth’s long-term supercontinent cycle. We want to understand how magmatic systems develop in late-stage rifts, as they control the delivery of magmas into the weakening rift crust and set the tempo of rift volcanism.

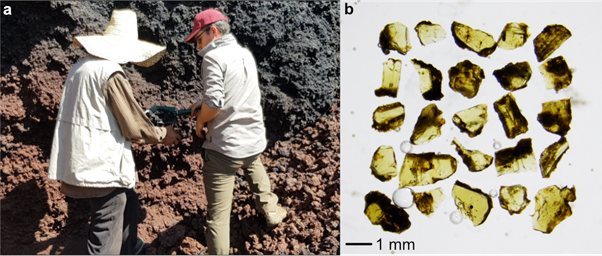

Sampling scoria in Ethiopia

Figure 1. (a) Main Ethiopian Rift scoria being collected from quarried cinder cones by Yared Sinetebeb (left; Addis Ababa University) and David Ferguson (right; University of Leeds). (b) Olivine crystals are collected from these scoriae for our study and mounted in epoxy resin for geochemical analysis. Credit: K. Wong (University of Cambridge).

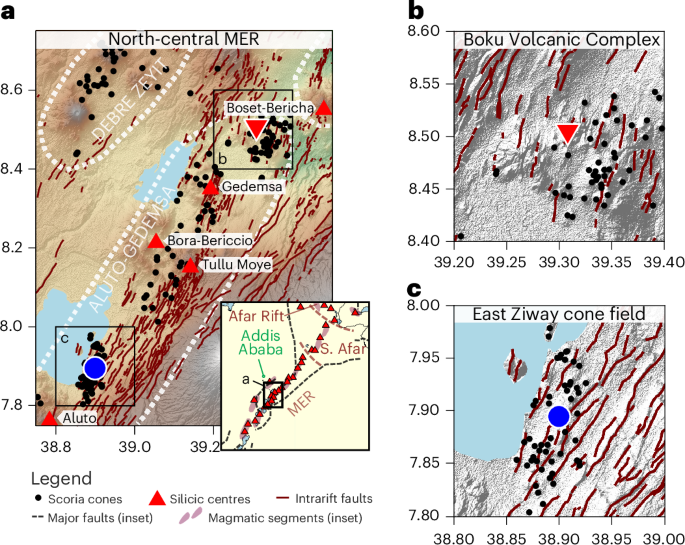

During my UKRI-NERC-funded PhD research at the University of Leeds (U.K.), we collaborated with researchers at Addis Ababa University (Ethiopia) to collect volcanic rock samples from the Main Ethiopian Rift. A geographical scar running north-east to south-west through the centre of the country, Ethiopia’s rift valley showcases many volcanoes and surface lava flows, implying that the magmatic stage of rift development is well underway. However, it must be considered an intermediate-stage rift owing to its thick underlying continental plate.

Our small team of geoscientists spent three weeks in the January sun digging sampling holes into small volcanic cinder cones along the axis of the rift valley to collect scoria (Figure 1a). Scoria — glassy volcanic ejecta — is locally used as a material for constructing roads, and quarries into these inert cones are common (see Poster Image). However, for geoscientists, scoria can also provide geochemical clues that reveal the anatomy of underlying magmatic systems. These quarries are therefore very convenient for exposing fresh samples!

What do olivine compositional zones reveal?

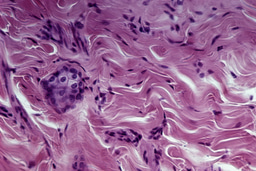

![Figure 2 Figure 2. (a, b) Examples of the olivine Fe-Mg compositional zonation patterns observed using scanning electron microscopy. The greyscale brightness of these images corresponds to the olivine Fe-Mg ratio, expressed as forsterite number (100 × Mg / [Fe + Mg]), with dark regions being richer in Mg (higher Fo) and light regions being richer in Fe (lower Fo). (c, d) Example inter-zonal diffusional models used to resolve timescales of magma movement from olivine zonation patterns. Adapted from Figure 2 in Wong et al. (2025).](https://images.zapnito.com/cdn-cgi/image/metadata=copyright,fit=scale-down,format=auto,quality=95/https://images.zapnito.com/uploads/CyYQf5lmSriasdehmcca_fig2.png)

Figure 2. (a, b) Examples of the olivine Fe-Mg compositional zonation patterns observed using scanning electron microscopy. The greyscale brightness of these images corresponds to the olivine Fe-Mg ratio, expressed as forsterite number (100 × Mg / [Fe + Mg]), with dark regions being richer in Mg (higher Fo) and light regions being richer in Fe (lower Fo). (c, d) Example inter-zonal diffusional models used to resolve timescales of magma movement from olivine zonation patterns. Adapted from Figure 2 in Wong et al. (2025, Nature Geoscience).

Back at Leeds, we handpicked olivine crystals from our scoria samples (Figure 1b). Olivine ([Fe,Mg]2SiO4) is one of the first minerals to crystallise from cooling magmas, and its chemistry mirrors the chemistry of the magma it formed from: high magnesium crystals correspond to high magnesium magmas, and vice versa.

Interestingly, our Ethiopian olivine crystals have compositional zones within them (Figure 2a, b), defined by differences in iron (Fe) and magnesium (Mg) concentrations within the olivine crystal structure. These zones develop when previously formed olivine crystals encounter new magma compositions as they navigate through the subsurface magmatic system, and crystallise crystal rims reflecting these new magma chemistries. Our Ethiopian olivine crystals have therefore passed through different magmatic environments as they’ve ascended towards the Earth's surface.

When first formed, these olivine zones are like tree rings — abrupt discontinuities that record the crystal’s magmatic history. However, at magmatic temperatures (≥1000°C), these zones can be erased by Fe-Mg diffusion within the crystal, smoothing out the chemical gradients between zones. Luckily for us, our olivine crystals were erupted before diffusion had completely annihilated their zones, preserving geochemical information on the different magmas our crystals encountered. By analysing the compositional gradients between olivine zones, and then simulating intra-zone diffusion rates with computer models (Figure 2c, d), we can estimate the time our crystals took to ascend through the Ethiopian crust, a journey of c. 15-30 km.

In short, these olivine crystals act as a magmatic stopwatch!

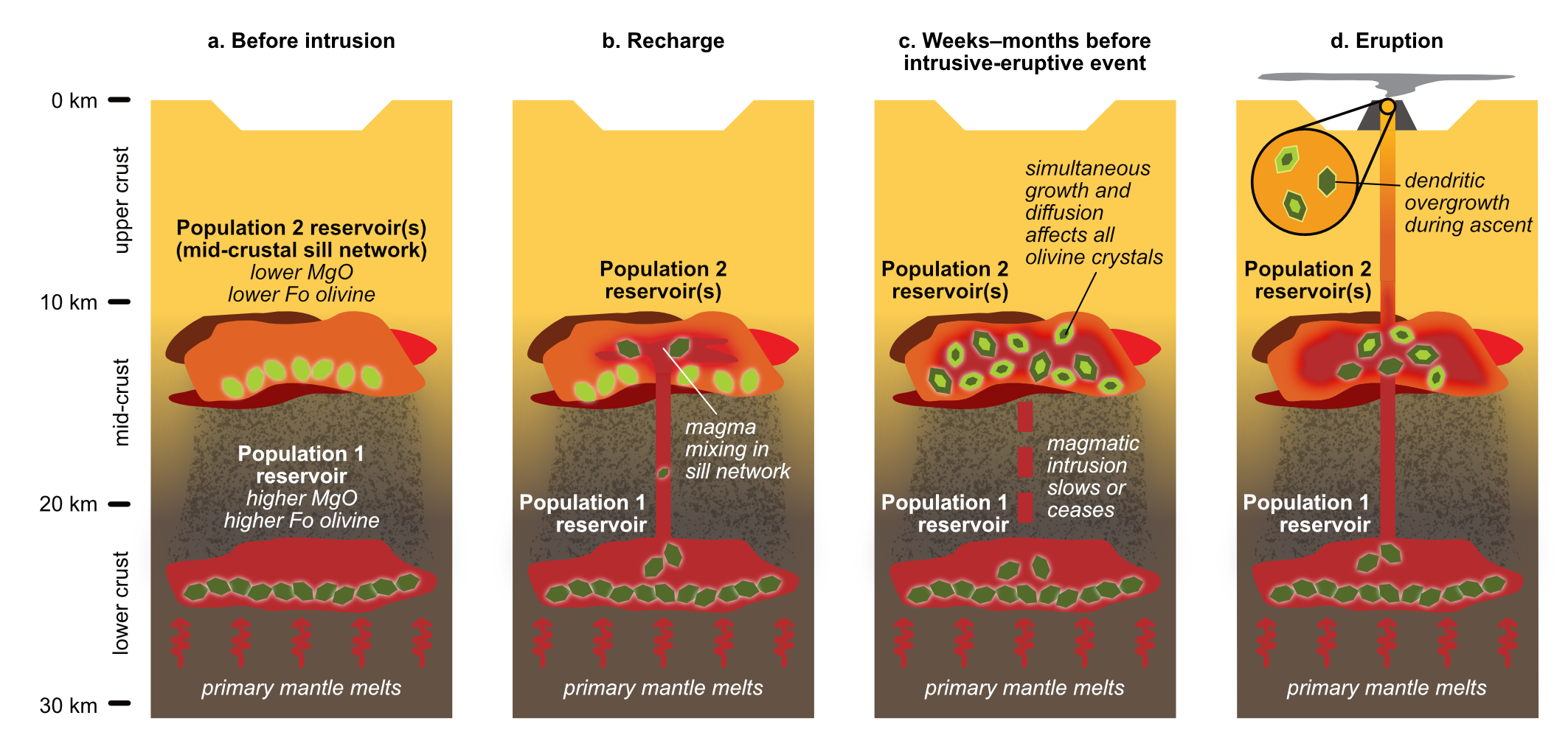

What does this mean for Ethiopian rifting?

Curiously, our olivine crystals, collected from two different Ethiopian cinder cone fields c. 100 km apart, have very similar zoning patterns. The diffusional timescales we obtain for both sample suites are also similar, and record events that occurred only weeks to months before eruption. There are common and consistent magmatic processes occurring along the Main Ethiopian Rift.

From these observations, we’ve developed a picture of how magmas transit the rifting Ethiopian crust (Figure 3). When new, hotter magmas ascend from the lower crust, they interact and mix with magmas already resident in the mid-crust. This mixing disturbs the chemical system between crystals and magmas, creating the olivine compositional zones that we observe. The final ascent of these magmas to the shallow crust and surface occurs relatively soon after, within a few weeks or months; this corresponds to the process of magmatic rifting itself. The short timescale between the arrival of new magmas in the crust and their eruption at the Earth's surface supports models of late-stage rifting episodes in Ethiopia sustained by rapid magma ascent rather than tectonic faulting.

Remarkably, the magma ascent process we propose for the Main Ethiopian Rift has strong similarities to those at late-stage rift zones where active phases of magma injection have been observed [2], such as the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland. We therefore suggest that, despite its intermediate tectonic maturity, the Main Ethiopian Rift has already developed an efficient magmatic system that can rapidly move magmas through tens of kilometres of crust, comparable to those underlying late-stage rift zones.

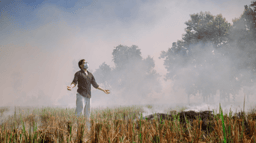

As a final note, I highlight the ongoing magmatic intrusion episode near the Ethiopian rift volcanoes of Fentale and Dofen that initiated last year [3], but has not yet resulted in a volcanic eruption. Interdisciplinary observations of magma movement beneath Ethiopia, collected both through geophysical monitoring of ongoing volcanic phenomena and through geochemical analysis of erupted materials (as demonstrated here), must therefore continue to be performed to characterise these rift magmatic systems for effective volcanic risk assessment.

References

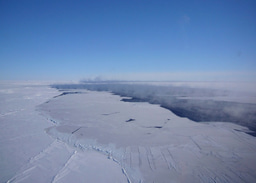

Poster Image: A quarry in a cinder cone near Ziway Lake, Ethiopia. These cones are made of scoria, glassy volcanic material that has travelled from kilometres deep within the Earth to explode at the surface. Geochemical analysis of this scoria allows us to examine the anatomy of rift magmatic systems. Credit: D. Ferguson (University of Leeds).

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Geoscience

A monthly multi-disciplinary journal aimed at bringing together top-quality research across the entire spectrum of the Earth Sciences along with relevant work in related areas.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Fluids in seismicity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Past sea level and ice sheet change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in