Mapping the Invisible: Translating Kinetic States into Structural Reality in P2X Receptors

Published in Neuroscience, Physics, and Protocols & Methods

The seed of this work was planted nearly two decades ago, in a frustration familiar to many ion-channel biophysicists. We described channels with “kinetic states” — closed, open, and the mysterious “flip” intermediate. These models fit the data, but they were physically abstract: the flip state was a mathematical box, not a physical movement in three-dimensional space. My long-term goal was to close that gap, to replace abstract labels with a model where every kinetic state corresponded to a concrete conformational state.

Earlier in my career I developed MacroR, a theoretically neat but practically limited method published in 2007. It treated macroscopic currents as effectively instantaneous, which is never true of real recordings that are always filtered and time-averaged. Within a couple of years I had both the theory and the code to relax that assumption and propagate probability distributions through finite integration windows. That extension became MacroIR: a Bayesian framework that works directly with time-averaged macroscopic traces, computes interval-exact likelihoods, and produces evidences for full kinetic schemes. The ambition was still the same: encode biological knowledge into mechanistic models and use Bayesian statistics to extract as much information as possible from experiments. I had already walked that path in earlier papers, but it felt like only a first pass at what this programme could do.

My route to the present study was nonlinear. I am, by temperament, a methodologist — an odd fit in environments where technique is relegated to the supplementary materials. When I started my group at INQUIMAE, resources were limited, so I made a conditional bet: if new grants arrived, I would keep pushing the wet-lab programme; if not, I would pivot fully to translating biological intuition into predictive models. The grants did not arrive. I began collaborating by building bespoke models for other people’s systems, and it quickly became clear that constructing them case by case was slow and fragile. We lacked a clear semantics — a grammar for how to turn biological stories into mathematical structures. That realisation sent me deep into physics, category theory, and homotopy type theory, looking for those rules. There was a whole landscape of possibilities there, and I was comfortable wandering in it.

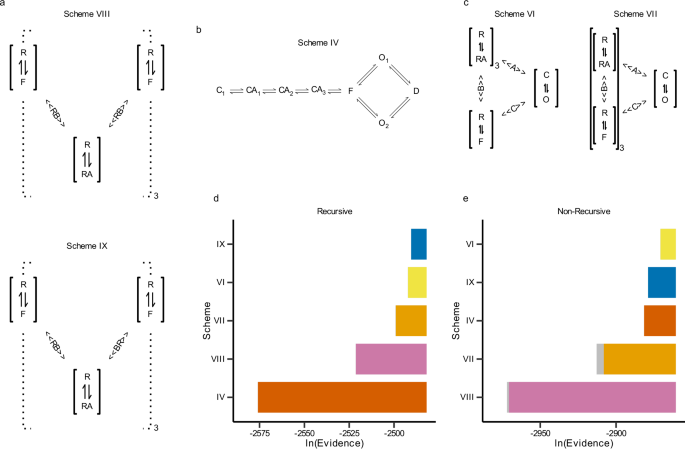

Eventually, however, the academic system asks for closure. I needed to bring those tools back to a concrete biological question, and the obvious choice was the system I knew best. I still had a rich dataset of ultrashort ATP pulses on P2X2 from my earlier work, but in that original paper I had analysed the recordings with simple least-squares fits. Without a reliable estimate of the effective degrees of freedom for time-averaged, filtered traces, those residuals could not be converted into a proper likelihood and therefore could not be used to compare kinetic schemes. MacroR was not an option either, because it assumed instantaneous, unfiltered measurements and could not be applied consistently to those macroscopic currents. MacroIR changed that. By working directly with time-averaged data, it provided a well-defined likelihood for each trace and, crucially, a Bayesian evidence that put alternative mechanisms on the same quantitative footing. In parallel, renewed analysis of P2X4 structures offered a structural “key” to reinterpret the old kinetic schemes in more physical terms. Together, they made this dataset the natural testing ground for the larger programme: biology → model → data → refined biology.

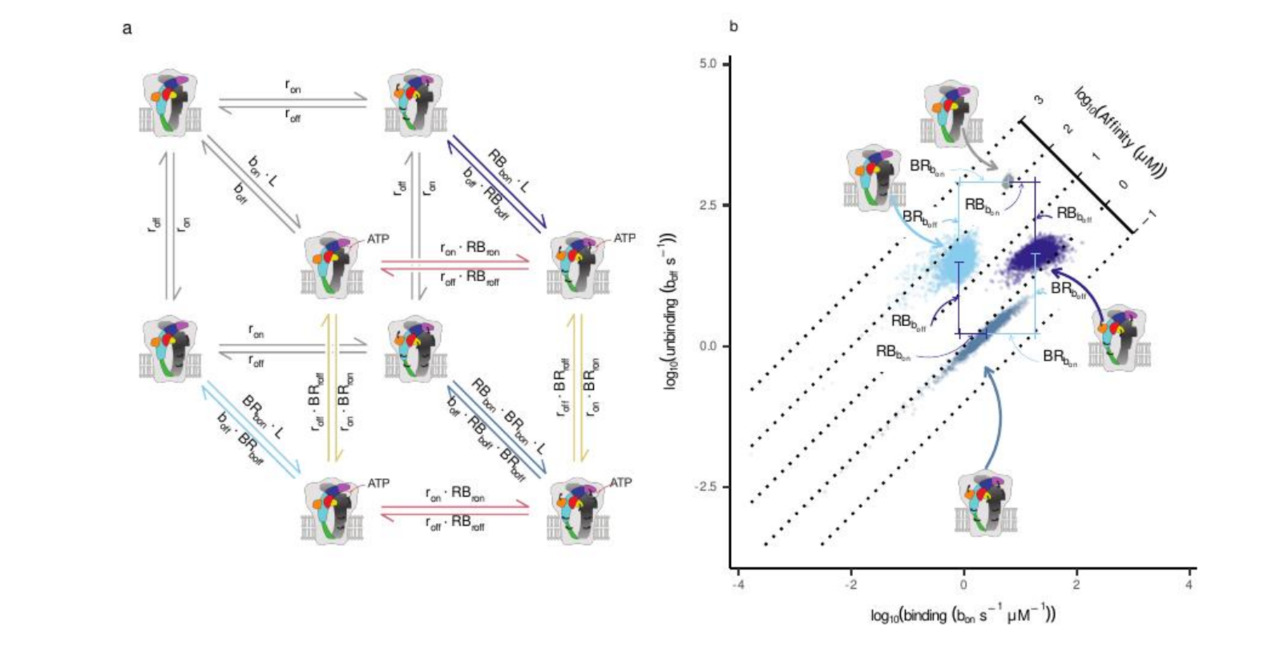

Two structural observations were crucial. First, the ATP-binding site lies at the interface between subunits, so each binding event couples allosterically to two neighbours. Second, much of the closed-to-open difference in the available P2X structures can be captured by a rotation of each subunit. That suggested a more economical description: perhaps we did not need additional abstract “flip” states at all, just two physical variables — ligand binding and independent subunit rotation. Allowing each subunit to rotate on its own would give enough degrees of freedom to capture the kinetics without inventing extra phenomenological states.

Even before that external push for closure, every piece of the puzzle was already in place: the theory behind MacroIR, a working implementation, the ultrashort ATP-pulse dataset on P2X2, and the renewed structural analysis of P2X4. But something was dragging me. A real test of MacroIR could not be just another fit to macroscopic traces; it had to show that the method could extract genuinely new mechanistic information, and that implied a long, careful analysis competing with more urgent tasks. There was also a more personal hesitation, familiar to many method developers: the quiet worry that, when you finally ask your own tool a hard question, it may tell you that the idea you have invested in for years does not actually work.

Once we committed to the analysis, the computational scale became clear. Each candidate scheme required propagating probability distributions through every integration window of the macroscopic currents and exploring a high-dimensional parameter space with tempered MCMC. On our 16–32-core clusters, a single model took from a couple of weeks to nearly two months to converge. I implemented a self-calibrating temperature ladder so that chains would mix across modes, and waited for the diagnostics to stabilise. When they finally did, the relief was real: the math behaved. We could now express the macroscopic current not just as “activation”, but as the probability of the channel having one, two, or three rotated subunits at each time point.

That mapping exposed the key surprise: a breakdown of symmetry.

Classical pictures of homotrimeric receptors often assume that all three subunits act in lockstep. Intuitively, I was attached to that view as well. But Bayesian model comparison was unforgiving. When we forced the models to map explicitly onto structural states, the evidence decisively favoured a conformational scheme (Scheme IX) in which ATP binding couples asymmetrically to the two subunits that frame each binding pocket. The best-supported fits were not symmetric: at a given interface, binding ATP strongly lowered the rotational barrier for just one subunit first, while its neighbour was only weakly affected. Crucially, this “favoured” subunit was not hard-coded; it emerged once we allowed subunits to rotate independently and let the evidence decide.

This is where the collaboration became essential. Gustavo Pierdominici-Sottile’s molecular-dynamics simulations broke the remaining ambiguity. In a closed P2X4 model with a single ATP bound at one interface, the domains of one subunit consistently moved further along the closed-to-open direction than those of its neighbour, as quantified by DCOT/DCOD analysis of the Head, Left Flipper, Dorsal Fin, and Lower Body regions. This identified the “first mover” at the structural level and allowed us to relabel the kinetic couplings so that the stronger interaction was always assigned to that chain. After this symmetry breaking, the previously bimodal posteriors collapsed into well-behaved, unimodal distributions.

Plotting the inferred free-energy barriers in this asymmetric model revealed a clean pattern. ATP binding selectively lowered the rotational barrier for the favoured subunit (our Chain A), driving its early rotation. That rotation, in turn, distorted the neighbouring binding pocket that Chain A also helps form, raising the barrier for the next ATP binding event. In other words, the first activation step did not simply “prime” the receptor — it partially occluded subsequent binding by reshaping the interface. This provided a mechanical explanation for negative cooperativity and reframed the classical flip state as a probabilistic manifestation of partially rotated, partially bound intermediates.

This project taught us the value of trusting your tools, but only after making them answer to structure. By refusing to settle for abstract kinetic states and insisting on a one-to-one mapping between kinetic and conformational states, we uncovered a sequential mechanism hidden in the interfaces. That level of detail is invisible to standard analyses of macroscopic currents, yet it emerges when you let the data, the structural information, and Bayesian inference speak to each other under a shared physical hypothesis.

(This work was completed in the middle of a sharp contraction of public funding for science and universities in Argentina — a contraction now deepening further.)

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in