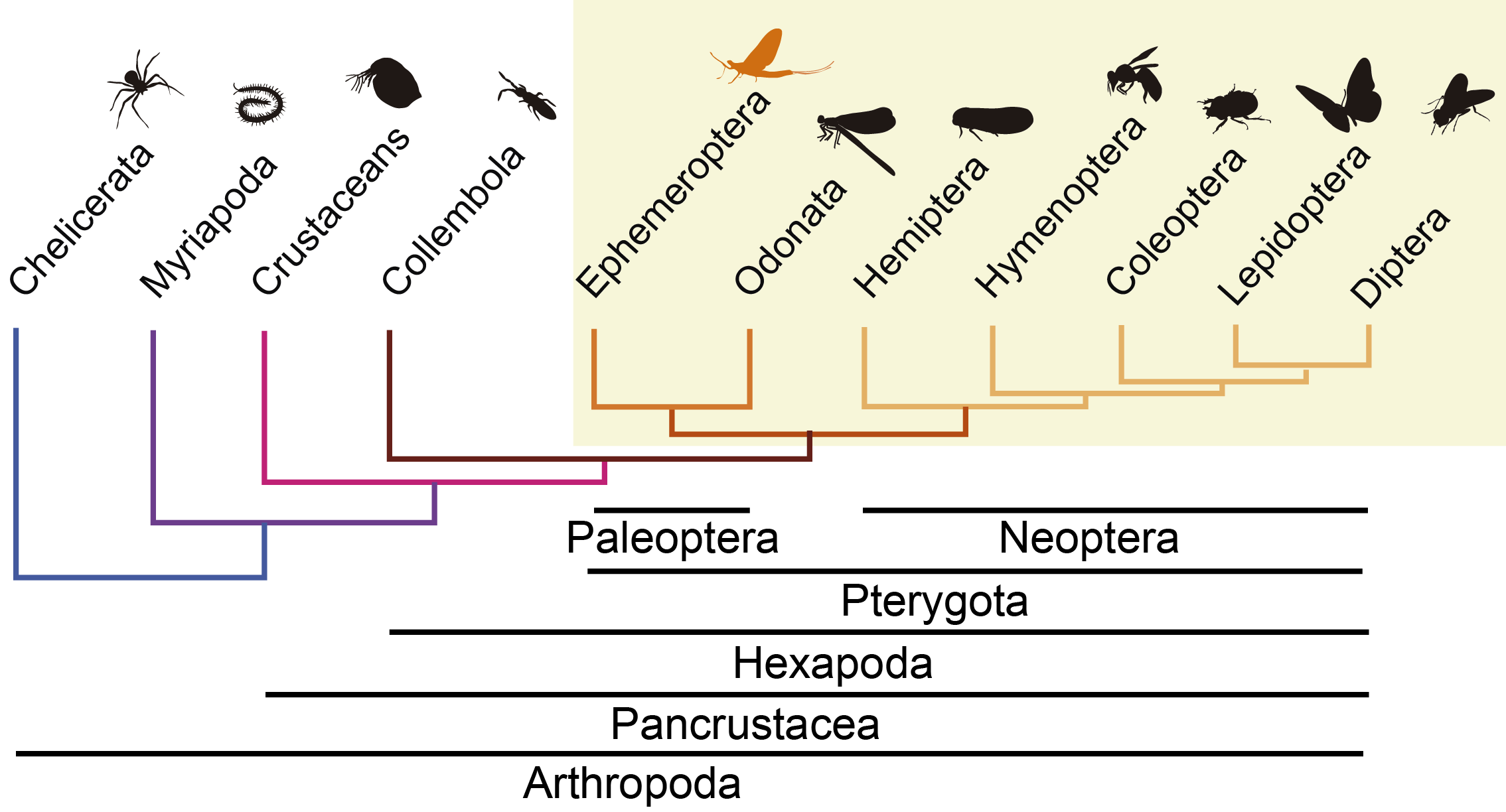

The origin of wings was the key innovation that allowed insects to become the most numerous and diverse group of animals on Earth; winged insects' diversification and adaptation to natural environments promoted the transformation of land ecosystems. As the sister group of all other winged insects, mayflies are a key group to investigate crucial morphological novelties in the evolution of this lineage. Furthermore, they are excellent to study adaptations to different environments since they exploit two completely different ecological niches during their life cycle: the juvenile stages (called nymphs or naiads) take place in the water, whereas adults are terrestrial and aerial.

In our article published in Nature Communications1, we investigated which are the changes at the genomic and transcriptomic level that promoted mayfly adaptations to these two distinctive habitats and which are the genomic signatures associated to the origin of wings in insects2.

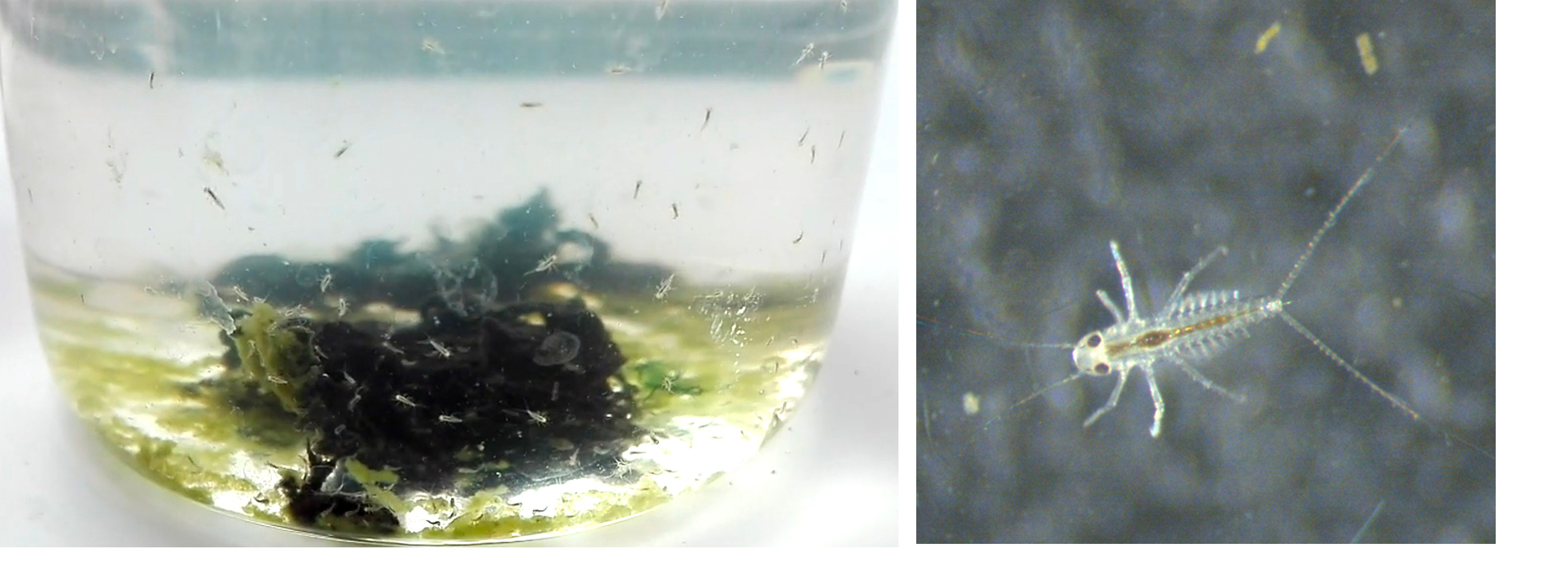

The entire project started five years ago, when I moved to the lab of Fernando Casares in Seville to investigate the origin and development of the male specific eyes (a striking sexually dimorphic new visual system called turbanate eyes due to their turban shape) of the mayfly Cloeon dipterum thanks to a Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellowship. Starting a new project always entails facing unexpected challenges, but in our case, (aspects as essential as) the mere obtainment of biological material was one of these challenges. So, at the beginning, we invested several months to successfully close the mayfly life cycle in the laboratory. Getting the appropriate food and water conditions was not the only difficulty; in the wild, mayflies mate while flying in huge swarms of thousands of individuals. Thus, we had to learn how to perform forced copulas between our mayflies in order to close the cycle and to establish a continuous culture in the laboratory3

Having an inbred line during several generations was instrumental to generate a high quality reference genome. We knew about experiences from other genome projects how important is to get the DNA of isogenic individuals (or a single individual if possible) to avoid issues with heterozygosity and haplotypes, so we had to be patient and wait for 11 months to have 7 generations of inbreeding to extract the genomic DNA.

Fortunately, once we had all the DNA and RNA samples, things went very smoothly, thanks to the excellent work of all the great collaborators that participated in the project. We decided to focus at first on few topics for which we thought mayflies would be particularly revealing, such as sensory systems and ecological adaptations and certain organs relevant for the origin of wings. Of course, this left many other interesting questions to be addressed in the future, not only by us, but by other labs interested in genomics and insect evolution.

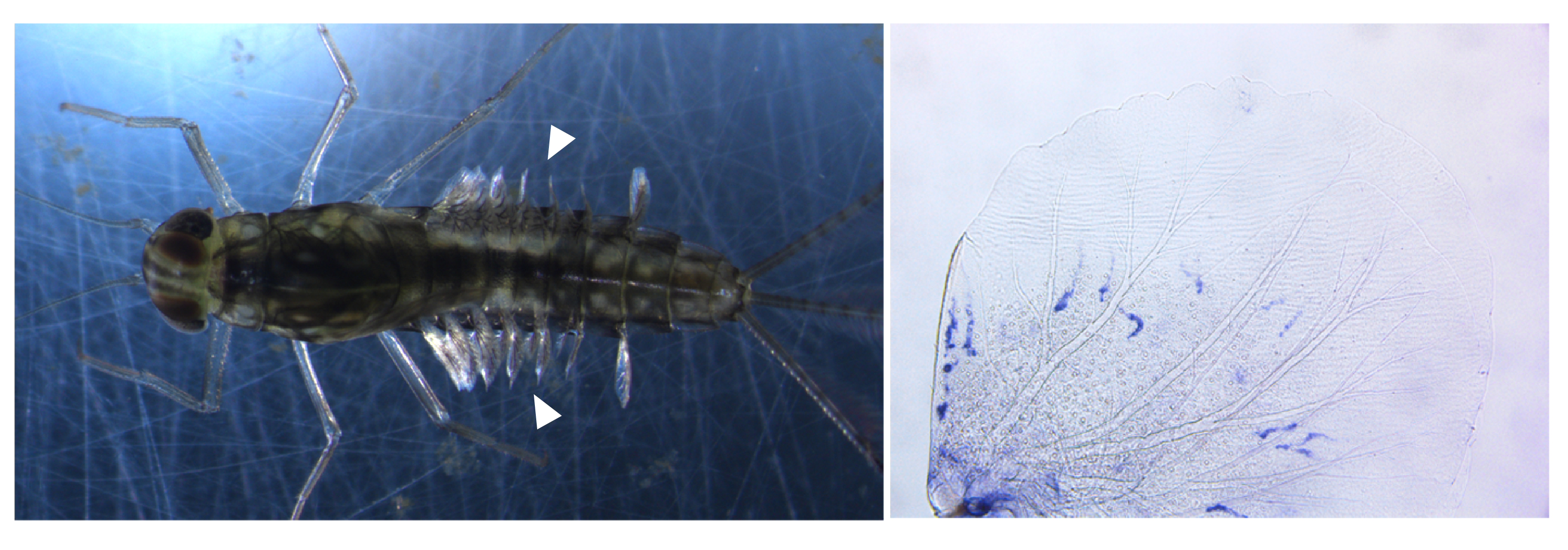

Although we knew that studying mayflies was going to be very important for those topics, as the project moved on, we started to realise that the genome and the transcriptomes of C. dipterum contained some unexpected features that we did not anticipated. We could have imagined that chemo-perception was important for mayflies while they live in the water, but we never thought that we would be able to propose a completely new function for the abdominal gills as sensory organs. In addition, our discoveries also challenge the idea that the evolution of some of these chemosensory genes were the result of the life on land, as they are predominantly expressed during aquatic stages. Another surprising finding was the large expansion of ultraviolet light-sensing opsins and their specific expression in the turbanate eye of males, which suggests some implications in mating behaviour and sexual selection. Finally, we describe deep conservation of gene expression between the fruit fly Drosophila, the centipede Strigamia maritima and C. dipterum and characterise novel players in wing development. Furthermore, we were also able to take the first steps towards unveiling the role of mayfly gills in the origin of insect wings.

However, the best part of this project

was to have the opportunity to work together with many different people around

the globe*. And the most exciting thing about this project is that it is just the beginning of the huge amount of wonders still to

be discovered about the genome, development and physiology of this tinny insect.

* This work has been possible thanks to the amazing work of all my co-authors: Joel Vizueta, Chris Wyatt, Alex de Mendoza, Ferdinand Marlétaz, Panos Firbas, Roberto Feuda, Giulio Masiero, Patricia Medina, Ana Alcaina, Fernando Cruz, Jessica Gomez-Garrido, Marta Gut, Tyler S Alioto, Carlos Vargas-Chavez, Kristofer Davie, Bernhard Misof, Josefa González, Stein Aerts, Ryan Lister, Jordi Paps, Julio Rozas, Alejandro Sánchez-Gracia, Manuel Irimia, Ignacio Maeso and Fernando Casares.

References

1. Almudi, I., Vizueta, J., Wyatt, C.D.R. et al. Genomic adaptations to aquatic and aerial life in mayflies and the origin of insect wings. Nat Commun 11, 2631 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467...

2. Clark-Hachtel, C. M. & Tomoyasu, Y. Exploring the origin of insect wings from an evo-devo perspective. Current Opinion in Insect Science 13, 77-85, doi:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2015.12.005 (2016).

3. Almudi, I. et al. Establishment of the mayfly Cloeon dipterum as a new model system to investigate insect evolution. Evodevo 10, 6, doi:10.1186/s13227-019-0120-y (2019).

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in