Pre-pregnancy BMI: A key determinant of the milk microbiota?

Published in Microbiology

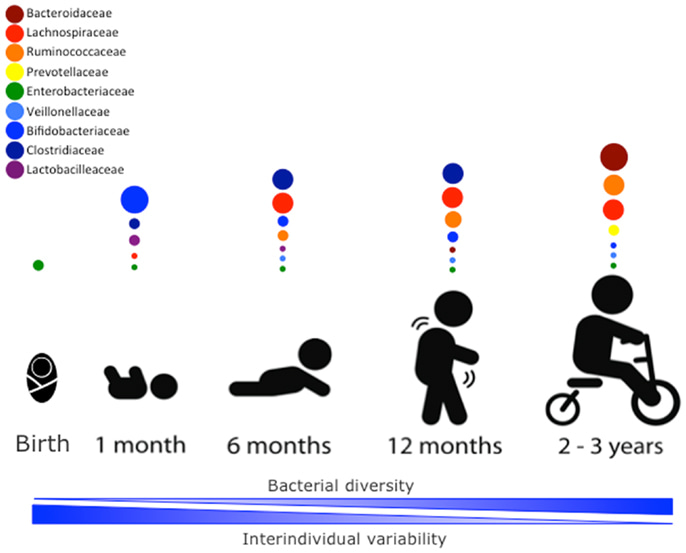

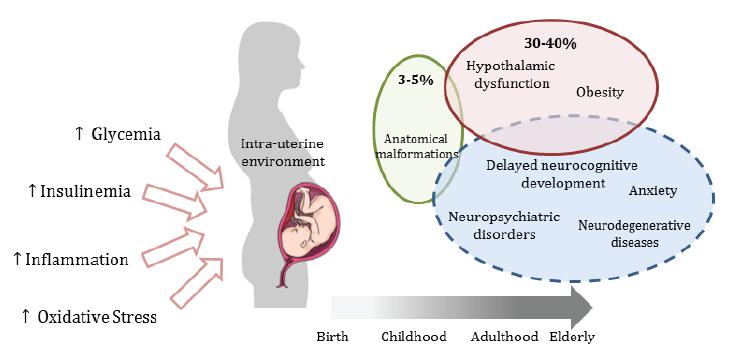

Long thought to be the result of contamination or maternal infection, research has now shown that human milk is a rich source of bacteria, termed the human milk microbiota1. Human milk contains 103-106 bacterial cells/mL in addition to a number of additional bioactive components including immune cells, oligosaccharides, lactoferrin, and lysozyme2–5. These constituents in human milk are transferred to human milk-fed infants and are involved in the maturation of the infant gut and immune system 6–9. Infant nutrition, either human milk or infant formula, during the first year of life may be associated with both short- and long-term health outcomes. It is thought that the absence of human milk, and thereby its bioactive components, negatively impacts immunologic and metabolic programming in the infant, which may contribute to a number of adverse health outcomes including increased risk of non-communicable diseases such as asthma, inflammatory bowel diseases, and metabolic syndrome10. A number of reports have examined how maternal health can alter the bacteria in human milk, which could then impact the microbiota transmitted to the offspring 11–13. Up to 20% of pregnancies in Canada present with gestational diabetes, which incurs significant maternal and infant morbidities14,15; despite this, no study to date has investigated the potential impact of gestational glucose intolerance, either impaired gestational glucose tolerance (IGT) or gestational diabetes (GDM), on the milk microbiota community structure or function. Our study strived to fill this gap and examine the associations between maternal metabolic, obstetrical, and demographic variables and the milk microbiota composition and predicted function in a cohort of women with varying degrees of gestational glucose intolerance.

The mothers in our study were recruited from a tertiary care hospital which follows higher risk pregnancies; this allowed us to recruit a cohort of women with high rates of either GDM or IGT. All mothers underwent an oral glucose tolerance test during late pregnancy at approximately 30 weeks’ gestation to determine their glucose tolerance status. We also collected a number of additional demographic (ethnicity), anthropometric (pre-pregnancy and postpartum BMI), and obstetrical variables (mode of delivery) to allow us to see a full picture of the factors interacting with the milk microbiota.

A rich microbiota was universally present across all milk samples, with significant inter-individual variability between moms at each bacterial taxonomic level. Our results demonstrate that the milk microbiota is a diverse ecosystem with each mother having their own unique milk microbiota signature. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was found to be the strongest predictor of the milk microbiota composition when it came to all three outcome measures: diversity, differential abundance, and predicted microbial functions. Pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with the predicted functional pathway “Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites”, which may point to the role of maternal BMI in altering the functions of the bacteria in her milk. In the case of “secondary metabolites”, this may mean the biosynthesis of antibiotics by certain bacteria to outcompete other bacteria in the milk microenvironment. Based on our findings, the directionality of the association in relation to pre-pregnancy BMI is unknown- i.e. is a greater BMI associated with a sub-optimal or beneficial milk microbiota? Although it may be tempting to assume a greater BMI is associated with an inferior milk microbiota composition, that has not yet been shown.

Gestational glucose tolerance status, ethnicity, and mode of delivery were also found to be associated with differentially abundant taxa, however, the associations between glucose tolerance status and milk microbiota composition were minimal after adjustment for other variables, including maternal BMI. This is contrary to what is seen in the gastrointestinal microbiota of individuals with type 2 diabetes, who display a divergent gut microbiota composition when compared to individuals with normoglycemia16. Seeing as the origin of bacteria in breast milk has not been fully elucidated, it is unknown why the milk microbiota does not appear to be dramatically impacted by gestational diabetes. Perhaps there are evolutionary adaptations in place to preserve the core integrity of milk microbiota in the face of short-term metabolic changes. This may be why greater associations were found between pre-pregnancy BMI and the milk microbiota. Pre-pregnancy BMI is likely representative of many more long-term confounding factors including maternal genetics, socioeconomic status, hormones, medications, stress levels, mental health, sleep quality, diet, and physical activity. Further investigation into the mechanisms between pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational glucose tolerance, and the milk microbiota are warranted.

The full paper was published in BMC Microbiology and can be found here.

Images from Bing images "Free to use and share".

References:

- Moossavi, S. & Azad, M. B. Origins of human milk microbiota: new evidence and arising questions. Gut Microbes 0, 1–10 (2019).

- Ballard, O. & Morrow, A. L. Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 60, 49–74 (2013).

- Lepage, P. & Van de Perre, P. The immune system of breast milk: antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 743, 121–137 (2012).

- Fitzstevens, J. L. et al. Systematic Review of the Human Milk Microbiota. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 32, 354–364 (2017).

- Boix-Amorós, A., Collado, M. C. & Mira, A. Relationship between Milk Microbiota, Bacterial Load, Macronutrients, and Human Cells during Lactation. Front. Microbiol. 7, 492 (2016).

- Azad, M. B. et al. Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months. CMAJ 185, 385–394 (2013).

- Murphy, K. et al. The Composition of Human Milk and Infant Faecal Microbiota Over the First Three Months of Life: A Pilot Study. Sci. Rep. 7, 40597 (2017).

- Pannaraj, P. S. et al. Association Between Breast Milk Bacterial Communities and Establishment and Development of the Infant Gut Microbiome. JAMA Pediatr. 171, 647–654 (2017).

- Victora, C. G. et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet 387, 475–490 (2016).

- Victora, C. G. et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet Lond. Engl. 387, 475–490 (2016).

- Moossavi, S. et al. Composition and Variation of the Human Milk Microbiota Are Influenced by Maternal and Early-Life Factors. Cell Host Microbe 25, 324-335.e4 (2019).

- Cabrera-Rubio, R. et al. The human milk microbiome changes over lactation and is shaped by maternal weight and mode of delivery. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 96, 544–551 (2012).

- Cabrera-Rubio, R., Mira-Pascual, L., Mira, A. & Collado, M. C. Impact of mode of delivery on the milk microbiota composition of healthy women. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 7, 54–60 (2016).

- Plows, J. F., Stanley, J. L., Baker, P. N., Reynolds, C. M. & Vickers, M. H. The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, (2018).

- Feig, D. S. et al. Diabetes and Pregnancy. Can. J. Diabetes 42, S255–S282 (2018).

- Gurung, M. et al. Role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 51, (2020).

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Microbiology

This is an open access, peer-reviewed journal that considers articles on all microorganisms - bacteria, archaea, algae and fungi, viruses, unicellular parasites and helminths.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Advances in microbial ecology

Microbial ecology is a rapidly evolving field that investigates how microorganisms interact with each other and their environments and respond to biotic and abiotic cues. Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies and multi-Omics approaches have significantly enhanced our understanding of microbial community structure, diversity and ecological functions across various terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, revealing the roles and impact of microorganisms on ecosystem functioning and biogeochemical cycles. Microbial ecology research is therefore essential to address pressing global challenges such as terrestrial and aquatic ecosystem degradation, biodiversity loss, and climate change, possibly improving ecosystem resilience and promoting environmental sustainability.

BMC Microbiology launches the Collection ‘Advances in microbial ecology’. This Collection invites contributions on microbial ecology research, focusing for instance on the impact, diversity and ecological functions of microorganisms in different environments, and in response to different (biotic and abiotic) stimuli. We welcome submissions that explore microbial interactions in different ecosystems, and the impact of microbial ecology for environmental sustainability and human health. Research without a clear focus on microorganisms, microbial communities, or microorganism-environment interactions will not be considered. We invite researchers and experts in the field to submit research articles covering a broad range of topics, including, but not limited to:

- Diversity, composition, structure and functions of microbial communities in different (terrestrial and aquatic) ecosystems and ecological niches

- Impact of landscape spatial heterogeneity and habitat fragmentation on microbial communities and functions

- The roles of microorganisms and microbial communities in biogeochemical cycles and nutrient cycling

- Microbial bioenergetics and metabolism in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems

- Response of microorganisms/microbial communities to biotic and abiotic stress in different natural habitats

- Impact of microorganisms and microbial biodiversity on ecosystem functioning, health, resilience and sustainability

- Microbial competitive strategies and ecological interactions (including microbe-host interactions)

- Microbiome-environment interactions

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 27, 2026

Current trends and future directions in mycology

Fungi are a diverse ubiquitous group of eukaryotic organisms, comprising e.g. unicellular yeasts as well as multicellular filamentous microorganisms and mushrooms. They exhibit remarkable morphological and ecological diversity and fulfil a wide array of biological and ecological roles as pathogens, decomposers, and mutualists. The field of mycology, dedicated to the study of fungi, has gained increasing importance in recent years, owing to both the beneficial and harmful impact of fungi on human health, agriculture, and the environment.

Recent advances in next generation sequencing, multi-Omics technologies, molecular biology and bioinformatics have significantly enhanced our understanding of the biology and ecology of fungi, as well as the complex interactions within fungal communities and their habitat. Research and innovation in fungal biotechnology have led to the development of antifungal agents, biocontrol methods, and the application of fungi in bioremediation and sustainable biofuel production. Meanwhile, research on fungal ecology has deepened our knowledge of the impact of fungi on ecosystem functioning and the implications of climate change on fungal diversity and distribution.

In support of United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being), BMC Microbiology launches the Collection Current trends and future directions in mycology. This Collection invites contributions to current research and future perspectives in mycology, covering a wide range of topics e.g., related to the fungal ecological roles and response to environmental changes, as well as novel biotechnological applications of fungi. Research without a clear focus on fungi, fungal communities, or host-fungi interactions will not be considered. We invite researchers and experts in the field to submit research articles covering a broad range of topics, including, but not limited to:

Molecular mechanisms in the development and pathogenesis of fungi

Parasitic fungi as models to study host-pathogen interactions

Taxonomy and phylogeny of fungi, with particular interest in poorly studied habitats and extreme environments

Resolving species complexes and generic concepts of speciose fungal genera

The role of saprotrophic fungi in nutrient cycling and ecosystem functioning

Diversity and ecological significance of endophytic fungi for plant health

Ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Impact of climate change on the distribution and function of fungal communities

The potential of fungal secondary metabolites for novel drug discovery

Mechanisms of antifungal drug resistance in pathogenic fungi

Mycotoxins in food security

Applications of fungal enzymes for sustainable industrial applications

Mechanisms of mechanosensing and fungal contact sensing

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in