Protecting species safeguards humankind

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Reading the poetic reflections of D.H. Lawrence is a reminder of the importance and interdependence people have with plants, but in particular grasses. On one hand, grasses have literally fueled the progress of human civilization. Wheat, corn/maize, oats, rye, buckwheat, barley, sugarcane, rice are all grasses that represent nutritional staples for people across the globe. On the other hand, as a plant ecologist devoted to researching the impacts and control of invasive grass species in Australia, it is astonishing to me the significant negative impacts an ill-suited grass can have on entire ecosystems and therefore people.

Planned introductions of grasses into Australia were made with the best of intentions, to improve the palatability and productivity of pastures for grazing livestock and to stabilize soils along eroded river banks, roadsides and mining sites. I honestly don’t think anyone could have predicted the impacts some of these species would have on biodiversity, aboriginal culture and agricultural production. On Earth Day 2019, I feel compelled to write about the negative impacts of one species, buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris), on biodiversity, ecosystem function and the impact on aboriginal people in Australia’s central deserts.

Buffel grass has been a conundrum species[1], in some circles you would elicit a heated debate describing it as an invasive plant, because it has been a valuable species for dairy and livestock production in many parts of Australia, even being described as the “King of pasture”[2]. Over time with its introduction and cultivation for agricultural production, it has spread widely into conservation areas and on to land where it was not intentionally introduced and is not desired[3]. Evidence of the negative environmental impacts of buffel grass is now undeniable[4]. The state of South Australia has prioritized these environmental impacts over agricultural benefits with buffel grass being declared a noxious weed in 2015.

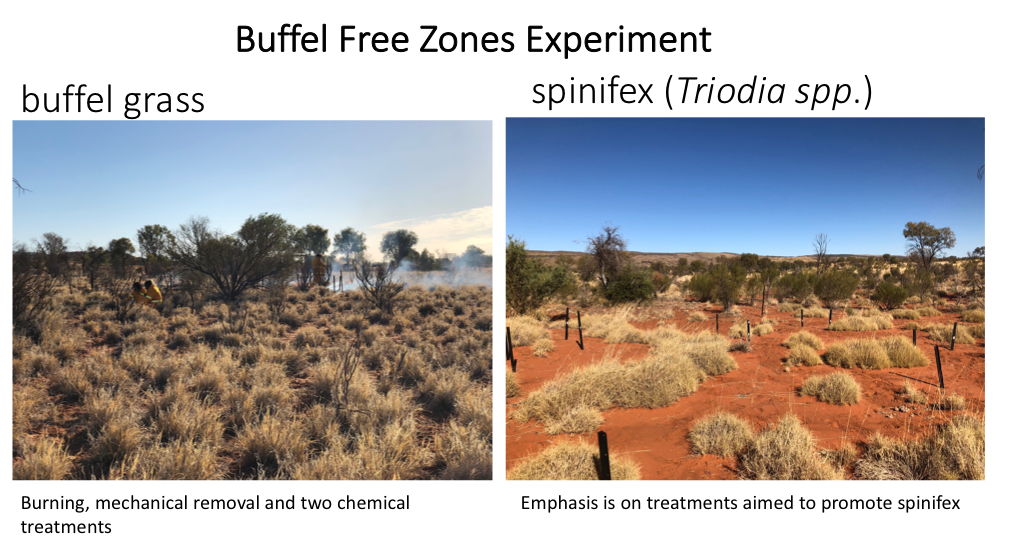

In many ways, buffel grass is a remarkable grass, able to grow lush tissue relatively fast in the most nutrient poor soils and driest landscapes arguably on earth. These high levels of biomass were valuable for rangeland production but a curse for native biodiversity. For example, when fires run through the shrublands of the central deserts which are held together by trees and shrubs and the endemic native grass species, Triodia spp (spinifex), and buffel grass is present fires run hotter and faster. With this additional heat, a positive feedback cycle is unleashed where trees, native grasses, and seeds banks are killed and more openings are made for buffel grass invasion as native plant species cannot compete with its growth rate and the native ephemeral plant species end up having less seeds and space available to grow when rain returns.

The Tjuwanpa Women Rangers, Western Arrarnta women, were the first all-female aboriginal women’s group in the Northern Territory, and they have been working together to care for country across five land trusts since 2013. The goals of the women rangers are to ensure their country remains strong into the future enabling their culture and teachings for the next generation. They are working hard to keep their language and culture strong. It is the role of Western Arrarnta women to teach their children about the collection, characteristics and preparations of native bush foods and medicinal plants. The spread and dominance of buffel grass across their country is making this important job very challenging. Increased abundance of buffel grass makes finding native animals and plants harder.

“Buffel grass is a big problem and worry for us rangers because it is destroying our bush food areas and habitat for little native animals. It chokes everything. Before you used to see lots of native animals running around like lizards and small native mice and lots of wildflowers after rain. Now in the areas where buffel has come in, you don’t see much, just buffel.

It makes fire burn really hot too and makes prescribed burning harder because it burns hot destroying the native trees you want to keep. It adds a big risk for wildfires in the hot months, adding lots of fuel.” says Lead Ranger Sonya Braybon who has been a ranger since the inception of the group.

Despite the challenges faced by the Tjuwanpa Women Rangers, they are committed to preserving the biodiversity on their lands. They are trialing different techniques to control buffel grass and are working together with other community members and scientists to track what works. This work is striving towards important buffel-free zones. The women aren’t waiting around for declaration of this species as a weed, they know it is a conundrum species; instead they are focused on making happen ground-up initiatives to bring back health to the landscape by managing for the return of native plant and animal species rather than the narrow focus and inefficient practice of just killing a grass---they are up against a new distorted ecological cycle that first needs to be disrupted.

It is not just the Tjuwanpa Women Rangers grappling with buffel grass in Australian deserts, other aboriginal communities and ranger groups are working hard to find a solution that works on their country such as the Aṉangu people from the remote Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) aboriginal lands (video below provides more details). Networks are beginning to come together with initiatives such as the buffel grass free Great Victoria Desert project. National park rangers still recovering from some of the largest fires to spread through the Tjoritja and Western MacDonnell Ranges fueled by drought, high temperatures and buffel grass[5] are also working towards protecting species, landscape and ultimately people.

Today on Earth Day spare a thought for the people grappling with the transformations buffel grass has made to the health of Australian desert landscapes but know that the cycle can be shifted back or in a new more resilient direction because protecting species means protecting our own species---our culture and civilization depends on it.

References

1. Friedel, M. et al., Buffel grass: both friend and foe. An evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of buffel grass use and recommendations for future research, Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre, Alice Springs, 2006.

2. Friedel, M. et al., Quantifying costs and benefits of buffel grass, Australian Government Land and Water Australia, 2009.

3. Firn, J. et al. (2015) Priority threat management of non-native plants to maintain ecosystem integrity across heterogeneous landscapes. Journal of Applied Ecology 52 (5), 1135-1144.

4. Marshall, V.M. et al. (2012) Buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris) as an invader and threat to biodiversity in arid environments: A review. Journal of Arid Environments 78, 1-12.

5. Schlesinger, C. and Judd, B., The summer bushfires you didn’t hear about, and the invasive species fuelling them, The Conversation, 2019.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Grasses are astonishing! Great communication of a complex issue. Understanding that some of our practices have far reaching consequences is vital for us to move forward as a biodiverse planet.