Quality of Life for Whom? Clashing perspectives between the state and communities

Published in Social Sciences and Sustainability

I set out to transform informal settlements with green spaces and regeneration. An ambitious vision, far too complex for a single study. I had to ask myself: why am I drawn to these research questions? The answer was simple, yet profound: quality of life. Now, that big vision of mine had to be dismantled and rebuilt, piece by piece. Urban planning policies often claim to pursue better quality of life for all, yet its recipients often seem dissatisfied. So what does quality of life really mean and for whom are we planning?

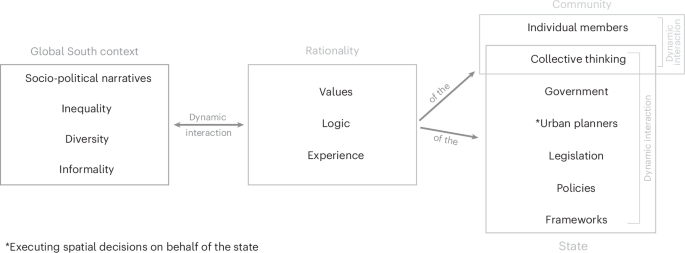

Rather than trying to solve the “big” problems at once, we wanted to focus on understanding the interplay between spatial planning and the lived realities in South Africa’s most vulnerable urban spaces. The number of protests in the country (an average of 11 per day) may tell us something about this. And so our research aim emerged: to understand whether the state’s vision of quality of life aligns with the lived realities of South Africa’s urban poor.

Then came another challenge: there was no clear set of indicators to measure quality of life, and the ones that exist often ignore African realities. Such indicators provide a breakdown of life quality, conveying values, interests and viewpoints. Now, if we don’t even know what to measure, how can we plan for it? To answer this, we turned to grounded theory – a method that let the data speak. We started with global quality of life indicators, then examined South African policies and finally listened to the voices of people living in low-income communities.

At first glance, the priorities for life quality of the state and the urban poor seem aligned, but the reality is much more complex. Policies promise futures of sustainable cities, but many communities are currently fighting to survive. Communities expect direct state action to improve quality of life, while the state aim for indirect feedback effects to achieve the same goal. Urban planning decisions cover whole cities, but when people see things differently, even good policies can miss the mark, ending up deepening exclusion instead of fixing it.

In the end, this work was about rethinking what quality of life truly means – and how urban planning can bridge the gap between vision and reality. Because, without that balance, the promise of a quality life for all risks slipping quietly through the cracks. As early career researchers, we often dream of tackling the “big” questions, but sometimes the most meaningful progress comes from laying the groundwork and to allow time to explore these questions one study at a time.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Cities

This journal aims to deepen and integrate basic and applied understanding of the character and dynamics of cities, including their roles, impacts and influences — past, present and future.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementLatest Content

Why is Singapore Identified in Global Research as Number One? How Physical Activity and Education Excellence Created a Global Leader

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in