Scientists are not the only ones asking innovative research questions to tackle climate change

Published in Earth & Environment

Belize recently leveraged our study on the societal and economic benefits of mangroves to update its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). NDCs are actions countries aim to take towards the global goal outlined in the Paris Climate Agreement of limiting the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees °C. However, designing specific measures and determining where and how to direct investments is hard, especially for nature-based solutions which reduce emissions and support adaptation through multiple pathways.

If there’s one thing that working in Belize has taught me, it’s that scientists are not the only ones who ask interesting research questions--and that hard problems are best tackled with partners. When World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Senior Program Officer in Belize, Nadia Bood first said to me, “Katie, we can use these models of the benefits of mangroves to set our blue carbon targets for the NDCs, no?”, my first thought was, "I don’t know yet, but it sure would be worth a try." After all, the magical mix of innovative science and real-world problems identified by Belizeans had come together before….

It was nearly 15 years ago. I was a newly minted postdoc at the Natural Capital Project (NatCap) at Stanford University. I was on the phone with another young woman, Chantalle Samuels. At the time, Chantalle was coastal planner at the Belize Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute. She now leads the agency as its CEO. Chantalle was explaining to me how the Belize Coastal Zone Management Act of 2000 calls for the development and implementation of a national-level Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan (ICZM Plan). The plan was to consider both national and regional scales, and be science-based, as well as informed by stakeholders and community members. The overarching goal of the plan was to address competing human uses of, and cumulative impacts to, Belize’s coastal and ocean ecosystems for the betterment of Belizeans and the global community.

Together our small band of coastal planners in Belize and scientists at NatCap would go on to talk by phone weekly for four years. We’d develop a suite of ecosystem service models and use them in collaboration with several agencies, non-governmental organizations, local coastal advisory committees, and many more Belizeans to design a preferred ICZM Plan (Arkema and Ruckelshaus 2017).

Belize ICZM Plan

Our results suggested that this plan would lead to greater returns from coastal protection and tourism than outcomes from scenarios oriented just toward achieving solely conservation or development goals. The Plan would also reduce impacts to coastal habitats and increase revenues from lobster fishing relative to current management (Arkema et al. 2014, 2015). In 2016, after more than six years of analysis, collaboration, and engagement, Belize approved the Plan. Hailed by UNESCO as “one of the most forward-thinking ocean management plans in the world,” the Belize barrier reef system was, in part, removed from the List of World Heritage Sites in Danger because of the protections provided in the ICZM Plan. The one thing the Plan did not explicitly do, though, was identify where and how much to invest in conservation and restoration of ecosystems for climate adaptation.

Mangroves along northern Ambergris Caye, Belize (Photo credit: Nadia Bood)

With this gap in mind, several years later, Nadia and a colleague at WWF dreamed up what would become the Smart Coasts Project. It sought to scale much of the participatory-science-based approaches we’d developed in Belize for the ICZM Plan to other countries in the Mesoamerican Reef Region—Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras—and use quantification of ecosystem services to inform nature-based solutions for climate adaptation. Nadia and I and many others had been working on that project for several years when it was time for Belize to update its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Climate Agreement. It was 2020, we were deep into the Covid-19 pandemic, everyone was frazzled with working from home, and countries around the world were delayed in submitting their updated NDCs by the 5-year deadline.

In their initial NDCs, many countries ignored the role of ocean and coastal ecosystems in climate mitigation and adaptation (Gallo et al. 2017). Those that included them tended towards descriptive actions such as “reduce deforestation” rather than specific, evidence-based targets such as the protection or restoration of a defined area of wetlands, mangroves, or other blue carbon ecosystems. Nadia and her Belizean colleagues wanted to do better.

With support from The Pew Charitable Trusts and World Wildlife Fund, Belize formed the National Blue Carbon Working Group. Consisting of representatives from government agencies, environmental NGOs, research institutions, and foundations, the aim of the working group was to help guide updates to Belize’s NDCs to include evidence-based targets for restoration or protection of mangroves and seagrasses. Next, we wrestled with articulating the specific questions we wanted to ask and the objectives of our analysis. Eventually we settled on 1) what are the carbon mitigation and additional climate adaptation benefits (i.e., "co-benefits") produced by a range of potential blue carbon targets? and 2) where should policies and actions be prioritized to maximize a suite of co-benefits?

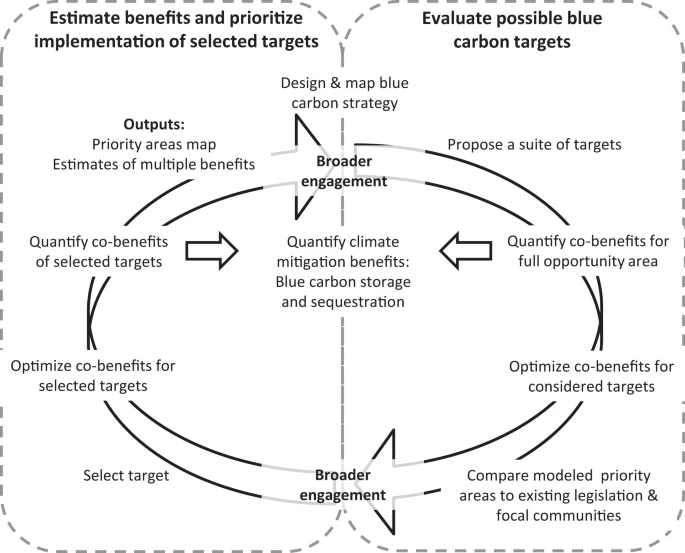

Iterative approach to evaluating potential blue carbon targets and prioritizing implementation of selected targets.

We then conducted two iterations of our analysis: first, to evaluate possible blue carbon targets for mangrove protection and restoration (right side of Iterative approach graphic above), and second, to estimate the benefits and prioritize the implementation of selected targets (left side of graphic above). We revised our inputs and our results based on regular input from the Blue Carbon Working Group and other officials involved in the NDC process.

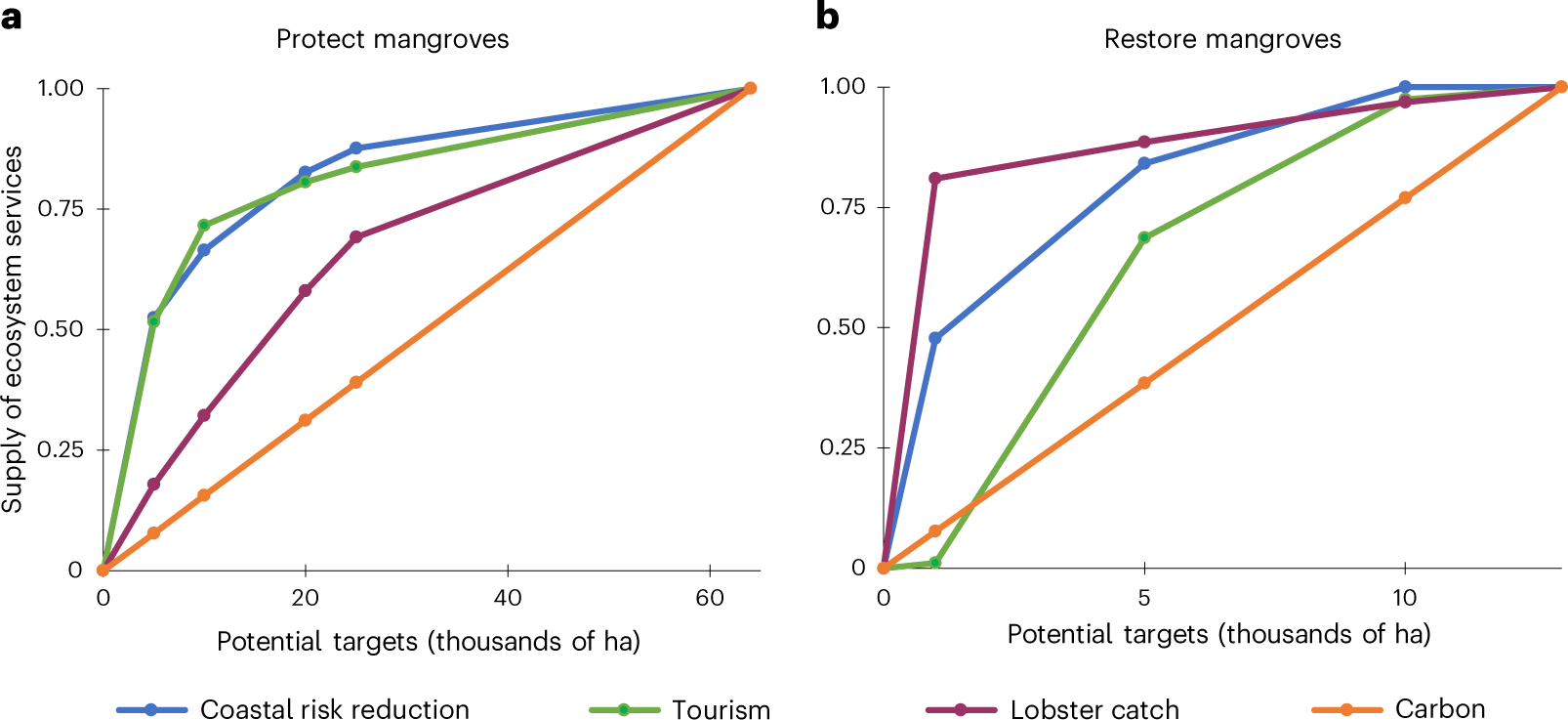

Figure 1. Benefits of potential blue carbon targets for mangrove protection (a) and restoration (b).

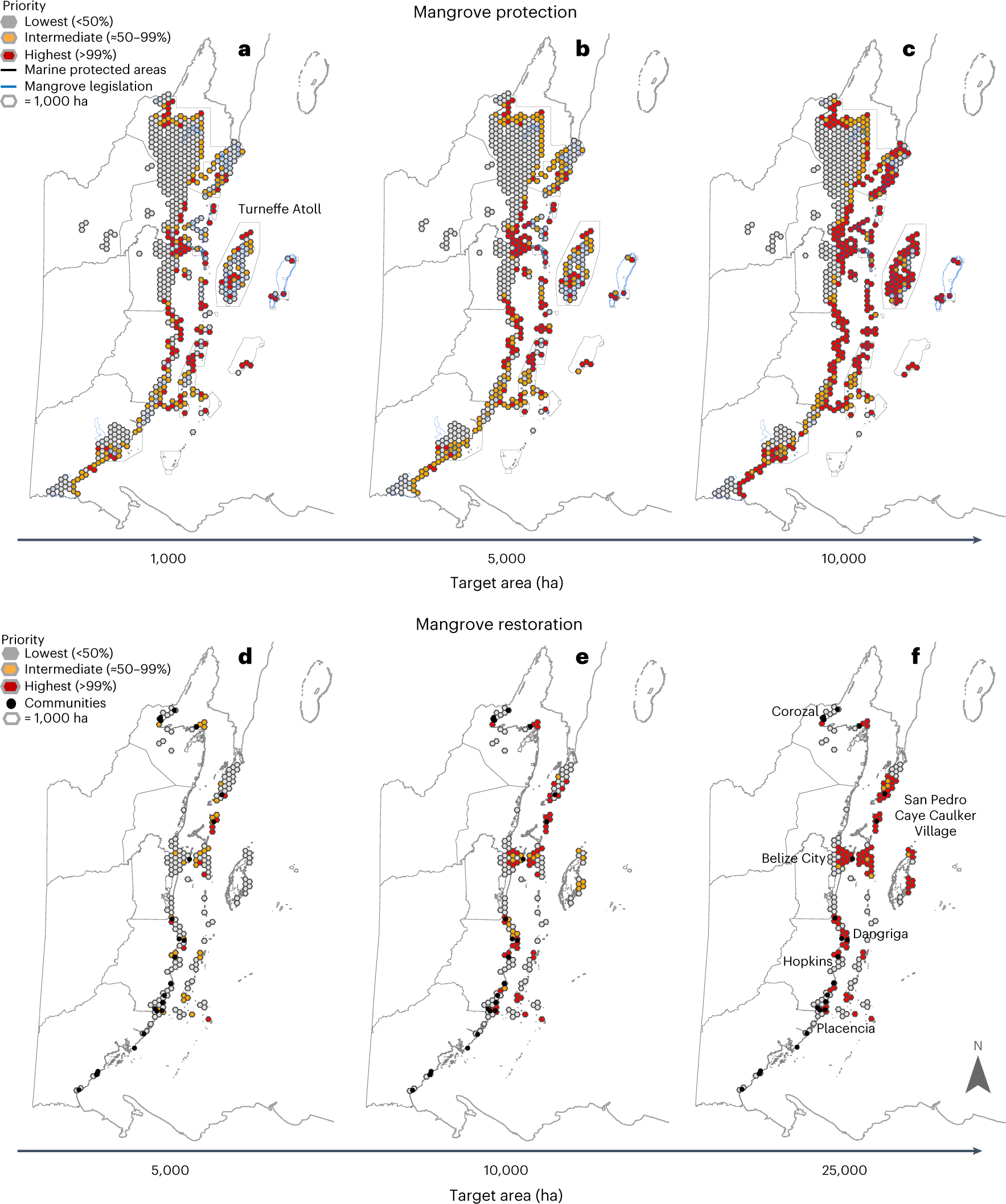

We found increases in carbon benefits with larger mangrove investments, while fisheries, tourism, and coastal risk reduction co-benefits grow initially and then plateau (Fig. 1). Figure 2 ended up being most useful for engaging with the working group and policymakers. By mapping the spatial extent of the highest priority locations for conservation and restoration with the locations of existing protected areas, and communities dependent on fisheries, coastal risk reduction, and tourism benefits of mangroves, we could identify where investments were most likely to meet needs of local populations.

Ultimately, our analysis helped to inform Belize’s updated NDCs--submitted to the UNFCCC in 2021--to include an additional 12,000 ha of mangrove protection and 4,000 ha of mangrove restoration, respectively, by 2030. Our study serves as an example for the more than 150 other countries that could enhance greenhouse gas sequestration and climate adaptation by incorporating blue carbon strategies that provide multiple societal benefits into their NDCs (Lester et al. 2023).

Figure 2. Priority locations for investing in potential mangrove protection (top row) and restoration (bottom row) targets.

Yet again, working closely with leaders in Belize to iterate between scientific analysis and management objectives led to novel research results and on-the-ground impact. Collaborating with Nadia, Chantalle, and others in Belize has been by far the most gratifying professional experience of my career. For a long time, scientists were discouraged from collaborating with policymakers and practitioners. I’m not that old and I remember it being unusual if not frowned upon in graduate school to consider the practical application of our ecological research. Fortunately for the state of the planet and society, things have changed. Transdisciplinary research that aims to meet pressing societal and environmental challenges is now recognized as a legitimate endeavor. Academic institutions like the University of Washington, and national laboratories, like the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, where I hold joint appointments, are trying to figure out how to engage communities as well as policymakers to co-develop novel solutions to grand challenges that can’t be solved from a scientific perspective alone. The next generation of PhD and master’s students are particularly fascinated by research that bridges science and practice – they want to make a difference outside the ivory tower, not just in the lab.

But as I tell my students when I share stories of Belize, it doesn’t happen overnight. Years of work and relationships laid the foundation for our efforts in Belize. And Nadia, Chantalle, and all our co-authors and collaborators over the years stand on the shoulders of giants—the people in Belize who began laying the groundwork for the ICZM Plan and nature-based solutions back in the 1980s and 1990s before “ecosystem services,” “nature-based solutions,” or “ecosystem-based management” were cool. They did it because they knew the resilience of their coastal country was intricately tied to the health of the corals, mangroves, seagrass, sand flats, and beaches of Belize. They did it because if they didn’t ask the interesting research questions and demand forward-thinking action, who else was going to do it?

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in