Severe diarrhea in newborns: Tiny tummy, big mystery

Published in Microbiology, General & Internal Medicine, and Immunology

The Viral Culprits

In the world of pigs, porcine enteric coronaviruses wreak havoc, causing severe gastroenteritis with infection rates soaring up to 100% in young piglets. These viruses, including Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus (TGEV), Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV), and Porcine Deltacoronavirus (PDCoV), are a constant concern for the pig industry due to their high infection and mortality rates in young suckling piglets. Researchers have long puzzled over why these tiny tummies are so vulnerable. The answer might lie in the mucus—a gel-like barrier that lines the intestines and other hollow organs.

The Role of Mucus

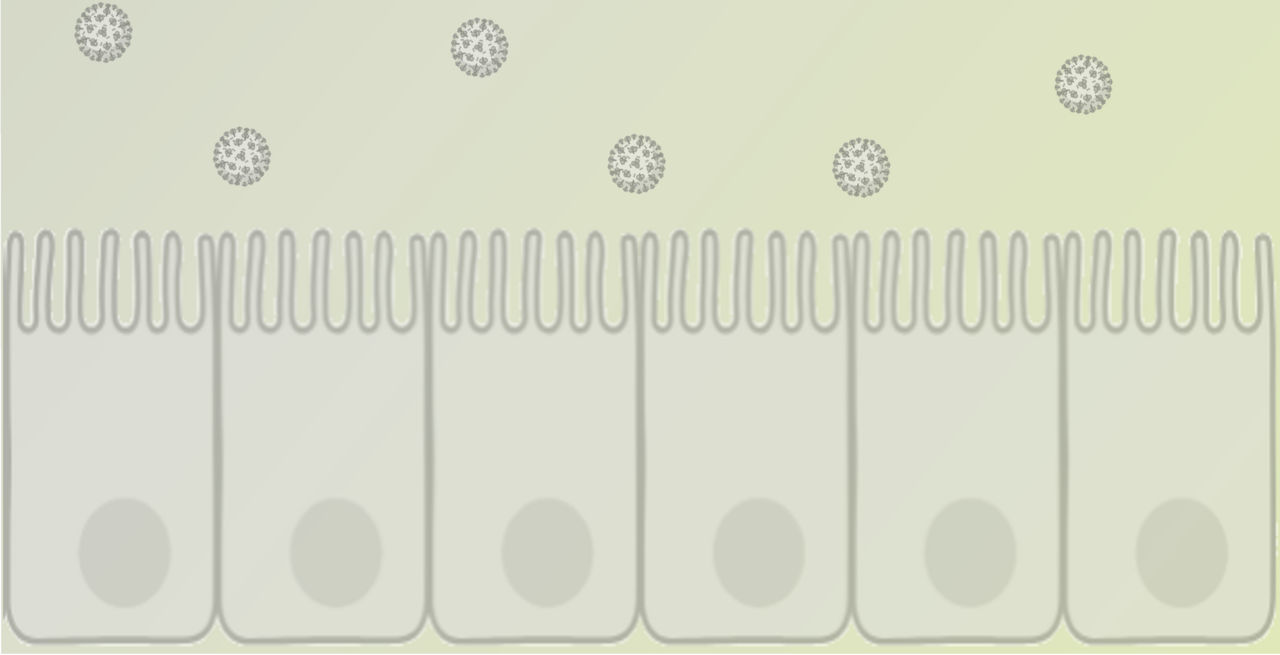

Mucus is a major part of the innate immune system, covering the hollow organs of most mammals, including humans. It provides a barrier against normal bacteria present in the body and invading pathogens like viruses. This mucus is a gel that consists mainly of water, with large glycoproteins called mucins giving it its gel-like properties. It also contains other proteins, lipids, and electrolytes. Specialized cells in the inner lining of hollow tissues, called Goblet cells, are responsible for the formation of the mucus layer. This layer changes in terms of quality and quantity with age.

Age-Related Changes in Mucus

Studies have demonstrated a protective effect of mucus and mucins against disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Mucus can either physically block pathogens by entrapment, inhibiting their access to target cells, or through chemical and immune entities present in the mucus. The changing parameters of these entities during infections can provide insights into their relation to disease pathogenesis. Researchers suspected that the severity of infection in young piglets could be related to these variations in mucosal components.

To investigate this, a study was conducted with four specific aims:

- To check the changes in the expression of important coronavirus receptors in three different ages of pig intestines.

- To investigate the changes occurring in intestinal morphology and mucus-producing cells of the intestines.

- To check the age-dependent blocking effect of intestinal mucus against TGEV.

- To see the age-related physical and chemical changes occurring in the pig intestinal mucus.

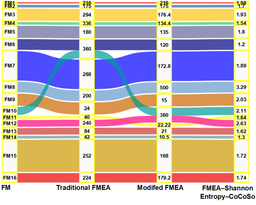

Changes in Intestinal Morphology and Mucus-Producing Cells

The study examined changes in intestinal morphology, the number of mucus-producing cells, and the expression of coronavirus receptors APN, DPP4, ACE2, and TMPRSS2 in pigs with aging. The expression pattern of these receptors was explored in four different regions of the intestines (duodenum, mid-jejunum, ileum, and colon) from three different ages of pigs (3 days, 3 weeks, 3 months). Immunofluorescence staining was used to visualize this pattern. The results showed that except for DPP4 in the jejunum, the expression of these receptors is highly variable and does not correlate with the age of the animal. Hence, the age-dependent susceptibility of animals to enteric coronaviruses is not dependent on the expression of these receptors.

This shifted the focus to changes in intestinal morphology and the number of mucus-producing cells. Using histochemical techniques, critical changes were observed in different regions of the intestines with aging. The main changes included an increase in the villus height-to-crypt depth ratio with aging, which affects nutrition absorption and mucus flow. The enterocytes, which are the main epithelial cells of the intestinal lining, increased in length with aging, which has significant implications for virus attachment and cell entry. Additionally, the number of mucus-producing cells increased with aging in all intestinal regions. These findings led to the conclusion that age-related changes occurring in intestinal mucus could help protect older animals against severe infections compared to newborn animals.

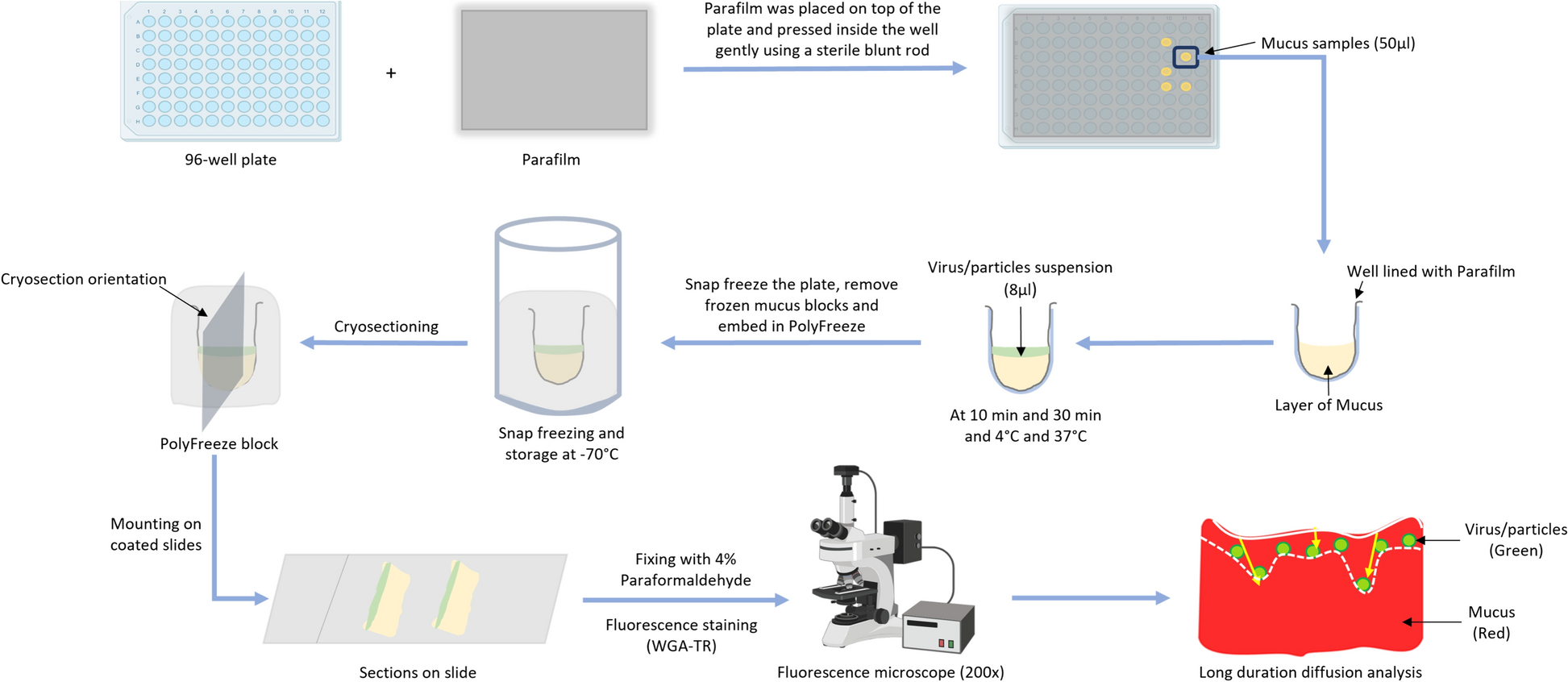

Protective Effect of Mucus Against Viral Infections

The age-dependent protective effect of porcine intestinal mucus against viral infections was explored in detail. The blocking effect of whole intestinal mucus extracted from 3-day and 3-week-old animals against TGEV was examined by tracking viral diffusion in the mucus and comparing the results with similar-sized, differently charged nanoparticles. The study showed that TGEV and control nanoparticles diffused freely in 3-day mucus while being hindered by 3-week mucus. Additionally, the protective effect of mucus against TGEV infection of susceptible ST cells was checked in the presence/absence of mucus. The results indicated that 3-week mucus has a significant TGEV-blocking activity compared to 3-day mucus, demonstrating the protective effect of intestinal mucus against viral infection and that the protective activity increases with age.

Physiochemical Properties of Mucus

The physiochemical properties of the mucus samples were also investigated. The flow pattern of mucus was measured in terms of viscosity using its rheological properties. The 3-week mucus exhibited more viscosity and less shear thinning compared to the 3-day mucus. Furthermore, mucus forms a meshwork of interlinked mucins that create variable-sized pores. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to assess the topography of these surfaces. The mean pore size for 3-day mucus was higher than that of 3-week mucus, with more than 80% of the pores in 3-day mucus being larger than the average diameter of enteric coronaviruses compared to only 50% in 3-week mucus. Additionally, the protein profile of the mucus samples was assessed using mass spectrometry. Higher levels of MUC13 and APN were found in 3-day mucus, while increased MUC2 expression was observed in 3-week mucus. These parameters are known to support higher infection rates in young pigs. Thus, it was concluded that physiochemical differences between the intestinal mucus of 3-day-old and 3-week-old pigs show key differences that could explain the decrease in viral susceptibility of older pigs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the immune system and genetics play their roles, the often-overlooked mucus might just be the unsung hero—or villain—in this tiny tummy mystery. Understanding these changes could pave the way for new treatments and preventive measures, ensuring healthier beginnings for both piglets and human infants. The study highlights the importance of considering age-related changes in mucus composition and structure when studying infectious diseases, virus tissue tropism, and developing therapeutics.

Follow the Topic

-

Veterinary Research

This is an open access journal that publishes high-quality and novel research and review articles focusing on all aspects of infectious diseases and host-pathogen interactions in animals.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Management of infectious diseases in animals: a global view of the current challenges

This Collection seeks to synthesize management strategies used to control infectious diseases in animals and their associated challenges. Each contribution will be framed around a central question (simple to state, but not necessarily to answer): “Given current knowledge, what are the key challenges in managing [disease name], and where are the most promising advances likely to emerge in the next decade?” We encourage papers to adopt a global perspective, enabling comparisons across different contexts (e.g., endemic vs. disease-free regions). Titles will follow a standardized format: “Management of [disease] in [host species]: a global view of current challenges.”

To structure the collection, we will pre-select a set of animal infectious diseases with major impacts on animal and/or human health. These will cover a broad range of host species (livestock, companion animals, fish) and pathogens (viruses, bacteria, parasites, prions), across different regulatory settings (local, national, and international). Internationally-recognized experts will be invited by the guest editorial board to assemble author teams with extensive expertise in managing the disease of interest and representing diverse epidemiological contexts worldwide. Contributors may include academic researchers, risk assessors, or risk managers. While most papers will be commissioned, unsolicited submissions are welcome if the lead author receives prior approval from the editorial board by demonstrating both the significance of the disease and the global expertise of the proposed author team.

The challenges addressed in each paper may relate to logistics, stakeholder engagement, acceptability, technical or technological limitations, regulatory gaps, evidence-based decision-making, or conceptual hurdles. However, these must be presented as specific and well-defined issues. Authors will be asked not to produce general overviews of diseases nor exhaustive reviews but to focus on operational and strategic challenges and to cite only a few carefully chosen references that provide context and support their arguments. This will be reinforced through limits on manuscript length and citation counts. Each paper should outline five to ten key challenges, offering informed perspectives rather than an exhaustive catalogue. Some overlap across papers is expected, as many diseases share common management issues. All submissions will undergo peer review by at least two leading experts to ensure that challenges are significant, clearly presented, and adequately grounded in prior work.

Each article will aim to be accessible and useful not only to researchers, but also to farmers, veterinarians, national veterinary authorities and international organizations (e.g., WOAH, FAO). The goal is to foster dialogue between science and decision-making. The overarching aim of this collection is to present a series of well-defined problems that require solutions, with the hope of inspiring risk assessors and managers to tackle them and strengthen our capacity to manage infectious animal diseases. Success will be achieved if, in the coming decades, many of the challenges described here become focal points for future research, policy discussions, or implementation frameworks. We are excited to play a role in advancing this progress.

Unsolicited submissions are welcome if the lead author receives prior approval from the editorial board by demonstrating both the significance of the disease and the global expertise of the proposed author team.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 2, Zero Hunger, SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being, SDG 12, Responsible Consumption and Production, and SDG 15, Life on Land.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Sep 22, 2026

Streptococcus suis, a major swine pathogen with zoonotic impact – advances in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control

Streptococcus suis remains one of the most significant bacterial pathogens affecting the global swine industry, responsible for substantial economic losses and serious animal welfare concerns. Beyond its impact in pigs, causing mainly meningitis, arthritis, sudden death and endocarditis, S. suis is an important zoonotic agent, causing severe invasive infections such as meningitis, septic shock and other infections in humans, particularly in regions with high levels of pork production and consumption. As such, S. suis exemplifies the necessity of a One Health approach, bridging veterinary medicine, sustainable animal production, and public health. S. suis is also responsible for one third of antibiotic use in post-weaned piglets.

In recent years, remarkable progress has been achieved in understanding S. suis virulence factors, host–pathogen interactions, population diversity, and mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance. Advances in surveillance, diagnostic techniques, immunology, and vaccination strategies are providing new opportunities for disease prevention and improved clinical management. At the same time, changes in pig production systems, global trade, and environmental pressures continue to shape the epidemiology and emergence of S. suis disease worldwide.

Following the 6th International Workshop on Streptococcus suis, that was held in Cambridge, UK in September 2025, this Special Collection brings together state-of-the-art research across the full spectrum of science on this pathogen. Topics include but are not limited to: bacterial genomics and evolution; virulence determinants; host immunity and pathophysiology; vaccines and immunotherapies; diagnostic innovation; epidemiology and transmission dynamics; antimicrobial resistance and stewardship; and clinical aspects in both pigs and humans.

Our aim is to highlight innovative findings, promote interdisciplinary exchange, and foster collaborative strategies to mitigate the burden of S. suis infections. By bringing together contributions from leading experts in the field, this issue will help guide future research priorities and support the development of effective disease control measures benefiting animal and human health alike.

We warmly invite submissions of original research articles, short communications, and comprehensive reviews.

Additional information:

The collection features contributions presented at the International Workshop and invites complementary studies that expand upon its themes.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being and SDG 12, Responsible Consumption and Production.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Aug 20, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in