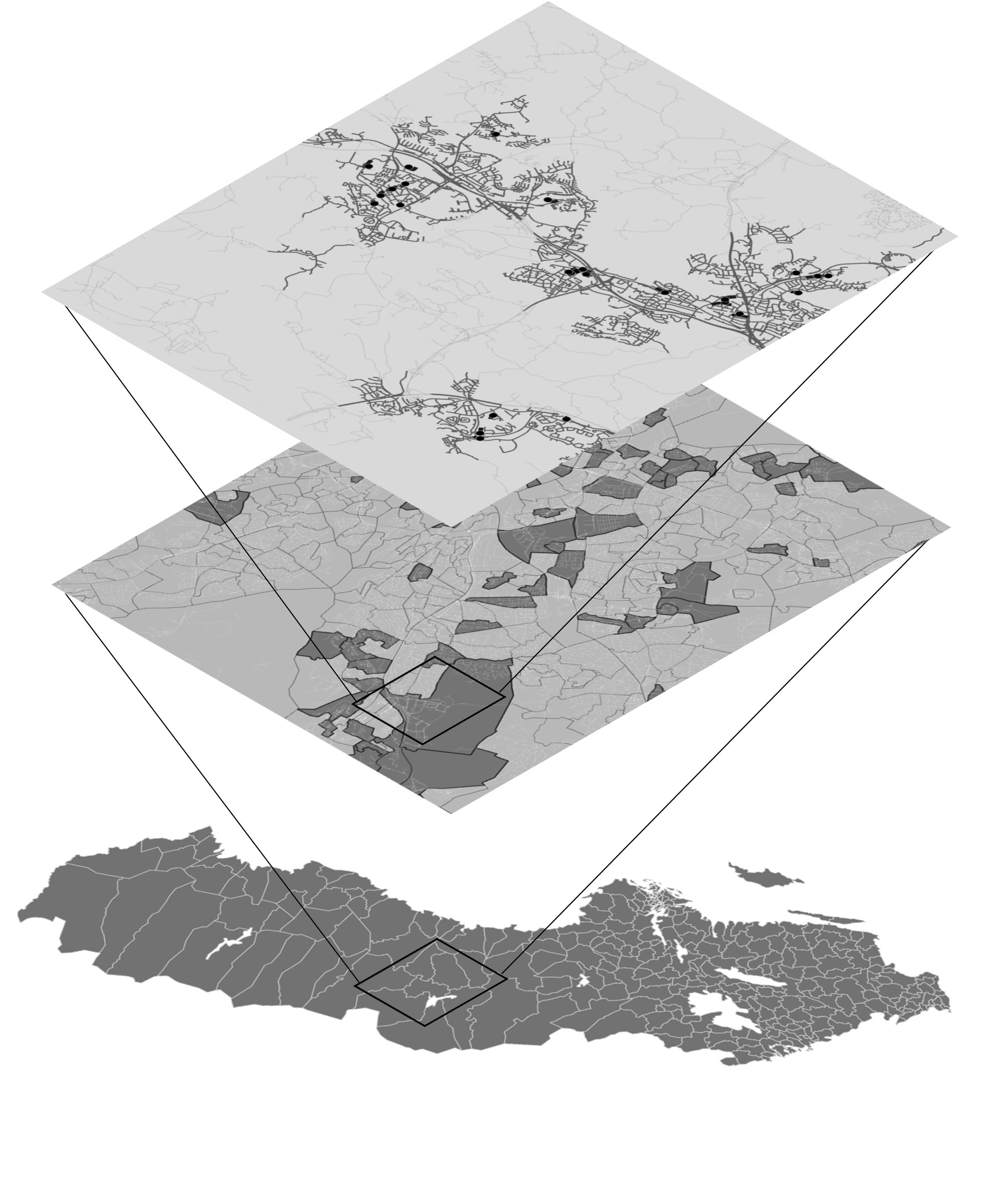

Shootings across the rural–urban continuum

Published in Social Sciences and Statistics

Firearm violence is uncommon, but when it occurs, it can lead to death and cause enduring physical and psychological trauma for victims, their families, and friends, affecting the entire community. Historically, shootings have been more prevalent in metropolitan areas than in rural communities (Evans & Taylor, 1995; Hemenway et al., 2020; Sturup et al., 2018). Utilizing principles from environmental criminology, this article examines the daily, weekly, and seasonal patterns of firearm violence across the rural–urban spectrum in Sweden.

Sweden constitutes an interesting case study. First, although the rate of lethal violence has been largely stable in the last ten years, the country has experienced an increase of more than 250% in gun violence (BRÅ, 2022). Half of this has occurred in smaller and medium-sized municipalities compared with one-third of these incidents occurring a couple of years ago, with a significant increase in violent encounters involving young males.

Using two different modelling strategies, we show that although the large majority of cases are concentrated in major cities, rural areas and smaller towns also experience gun-related incidents and that the prevalence and patterns may differ, which impose different prevention

strategies and research challenges. Firstly, demographic diversity and socio-economic variability within the rural-urban continuum can differ vastly, even over short distances,

making generalizations about shootings difficult even within municipality types. Secondly, the availability and quality of data on incidents of violence can be inconsistent, as reporting mechanisms and police capabilities may vary between more urbanised and more remote

rural areas within the continuum. Additionally, cultural factors, including attitudes toward gun ownership and law enforcement, can significantly influence both the occurrence of shootings and the community’s responses to them. This complexity requires a nuanced approach to

research that accounts for the heterogeneity of the rural–urban continuum, demanding new ways to address the multifaceted nature of shootings in these areas.

Although in Sweden, common shooting locations for young people include areas near playgrounds, parks, places with poor supervision, and areas facilitating escape, such as industrial zones and public transit points and restaurants, changing these environments will most certainly not affect the mechanisms that lead to these shootings, or if they do, only marginally. It would be necessary to have an in-depth knowledge of the mechanisms

linking offenders and victims in the particular places and situational conditions where shootings occur. This could contribute to a better understanding of the meaning of these settings for those involved in these conflicts.

The key to effective prevention is recognising that a one-size-fits-all approach may not work when dealing with firearm violence in diverse settings. In rural areas, in particular, police and community organisations can work together to engage with residents, especially young

people. Reducing firearm violence demands a combination of strategies, including knowing the main motivations for these shootings, understanding links with drugs and organised crime and improving community policing practices.

Law enforcement agencies can revise the allocation of resources by focusing on patrolling and monitoring these high-risk neighbourhoods and interstitial areas at particular times. Investing in programmes that target youth at risk, offer alternatives to gang involvement, and provide mentorship can help reduce the number of young individuals drawn into gun-related crimes.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in