Starve a cold

Published in Biomedical Research, General & Internal Medicine, and Immunology

Explore the Research

Just a moment...

secure.jbs.elsevierhealth.com needs to review the security of your connection before proceeding.

One thing you have probably noticed when you have an infection is a profound loss of appetite? In healthy adults, this could be seen as something of a blessing, it can have much more serious consequences, particularly at the extremes of age. In the elderly, the after effects of respiratory infections can accelerate frailty and the loss of independence. In the very young, not feeding can lead to dehydration and possibly contributes to more severe disease.

One thing you have probably noticed when you have an infection is a profound loss of appetite? In healthy adults, this could be seen as something of a blessing, it can have much more serious consequences, particularly at the extremes of age. In the elderly, the after effects of respiratory infections can accelerate frailty and the loss of independence. In the very young, not feeding can lead to dehydration and possibly contributes to more severe disease.

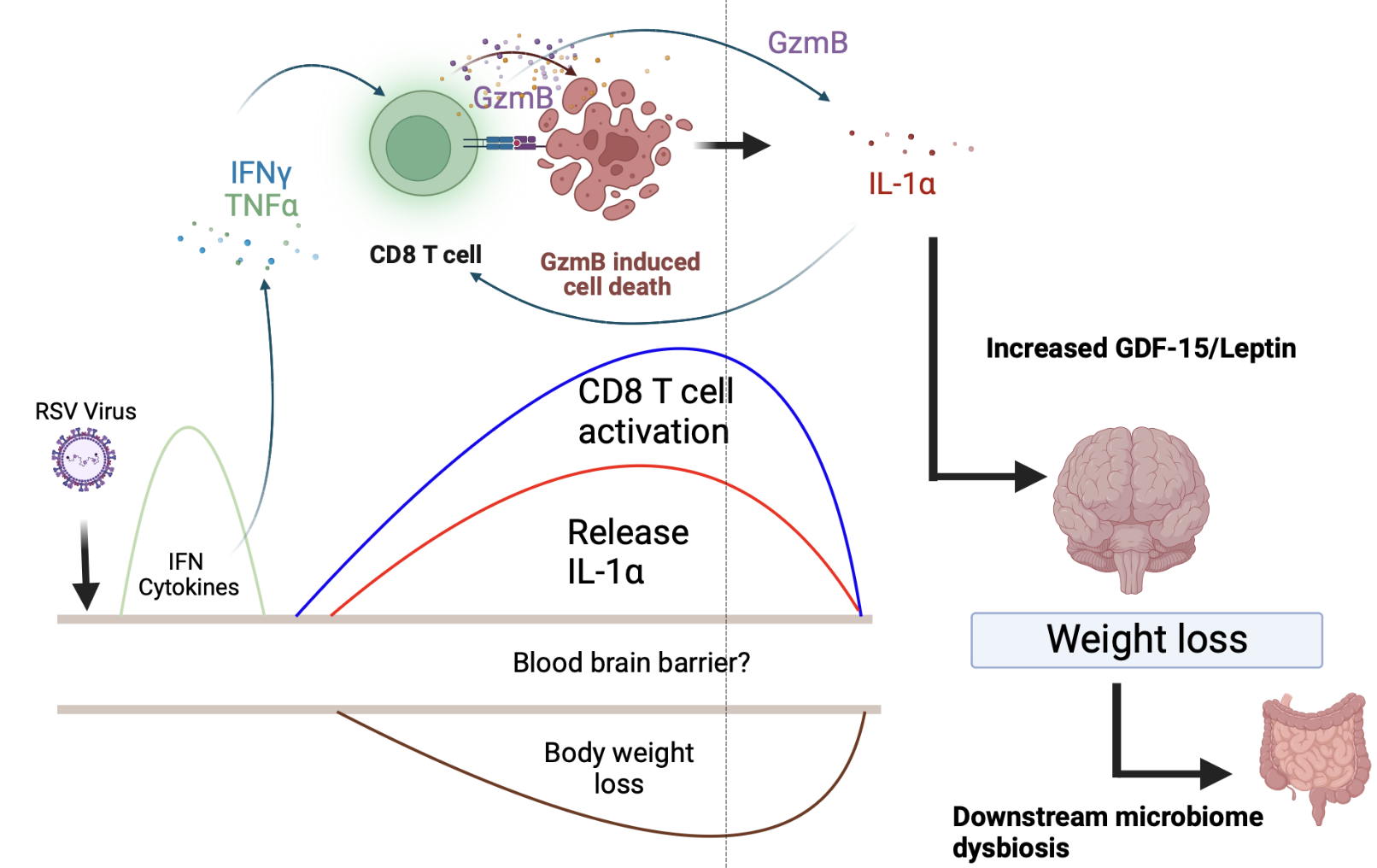

In previous studies, we observed that the loss of appetite was associated with the immune response to infection. We were interested as to what might drive the loss of appetite – with a view that understanding how it occurs might lead to approaches to reverse it. In particular we wanted to understand one component of the immune response – the cells that are recruited to the lungs to fight off infections and the way that they communicate with other cells.

In our recently published study we looked at one of the signals produced by immune cells, a molecule called Interleukin 1 alpha (IL-1α for short). Cells release IL-1α to warn the rest of the body that an infection is happening and as a way of recruiting reinforcements to help in the fight. We saw that the peak of IL-1α release into the lungs just precedes the weight loss, and therefore suspected it played a role. To test our hypothesis (IL-1α causes weight loss during infection) we took two approaches. Firstly, we blocked it during the course of infection; when blocked there was no weight loss. Secondly, we added IL-1α by itself; when we did this, we observed weight loss. Put together, these observations strongly suggest that IL-1α released by immune cells reduces the appetite, and leads to weight loss.

We then looked deeper into how this might happen. And we found a really striking result – IL-1α levels increase in the brain during infection. We think this is linked to an increase in permeability between the brain and the rest of the body, which allows molecules to enter the brain which would otherwise normally stay outside. The IL-1α in the brain then triggers a cascade of hormones, in particular one called leptin, which is linked to feelings of satiety (if leptin goes up, you feel full and stop eating). Famously mice lacking the leptin gene are enormously fat because they never stop eating.

One other curiosity in our results was that when the mice stop eating, the bacteria in their guts change. These changes increase certain families of bacteria – some of which are linked to recovery from infection. This suggests the intriguing possibility that there is a protective value in not eating when you have a cold, because it increases protective bacteria – we have yet to explore this fully.

Overall, we have dissected a pathway that links the immune response to infection to a loss of appetite and discovered a key appetite regulatory role for an immune molecule IL-1α. The next step is to explore how this can be approached therapeutically.

Follow the Topic

Ask the Editor - Immunology, Pathogenesis, Inflammation and Innate Immunity

Got a question for the editor about the complement system in health and disease? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in