Suicide during the COVID-19 in Japan

Published in Social Sciences

Mental health consequence —and suicide as a more expressing scenario— of the COVID-19 pandemic seemed to matter a great deal. The prolonged uncertainty, fear, and anxiety about infections, precautionary social isolation, and economic disruption all can deteriorate psychological health. At the early stage of the disease outbreak, without effective viral treatment and vaccinations, society had expected this pandemic could last for a long period, raising grave concern on people's mental well-being. Using the historical unemployment-suicide relationship, a study found that the COVID-19 and the economic disruptions can significantly increase suicide deaths by even 20-30%.

However, an early report from Japan documented the opposite, showing much lower suicide deaths than the past few years (March and April 2020). This unexpected and striking report raised me a strand of questions.

How many was the number of suicide changed during the pandemic if assessing rigorously? What are the driving mechanisms? Would the trend continue or discontinue?

Looking backward, none of the existing studies around the world was able to answer these questions. These require updated and reliable suicide data that can represent a whole population in a region or country. However, such data are often published with delays of several months or a few years. Fortunately, Japan provided exceptionally harmonized data, which cover all suicide records in a nation, are stratified by gender, age, and occupations, collected from more than 1,800 cities, and always published within a month or so. I consulted with Dr. Okamoto, and it did not take even a moment for us to agree to launch the project. Indeed, we were very excited.

After extensive efforts, we soon published the first working paper and received revision requested by the Nature Human Behaviour. It was fortunate that we had opportunities to include the most updated data during the revision. Eventually, our paper used data up to October 2020 and was published in January 2021, which allow researchers and policymakers to digest our findings in a timely manner. While the early report found the reduction in suicide, the trend was found to break within a few months since then. Here we summarize three main takeaways from our paper.

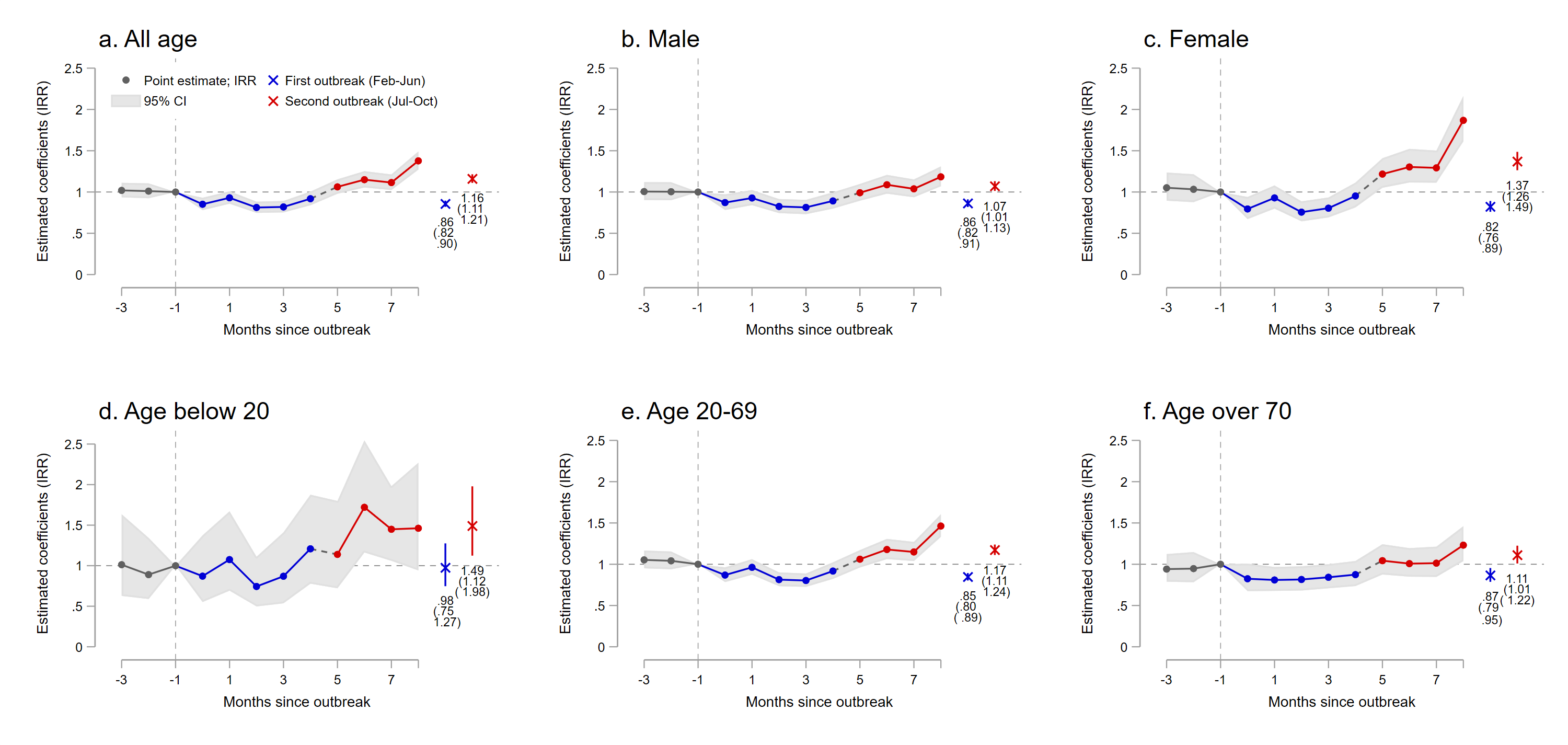

First, we find a notable reduction in suicide rates during the first outbreak (February to June 2020, blue line in figure) consistent with the report. It declined by 14% relative to our control scenario, in which we used Difference-in-Difference to construct the plausible counterfactual without the COVID-19. The finding may have been unexpected, yet a recent study, which used data from 21 countries, also found suicide did not increase in most countries at an early stage of pandemic. We might think this could be because of people's psychological response (People may avoid dying when everyone is afraid of dying with infections), and governments' generous subsidy to households (every citizen received about $940USD) and firms (the number of bankruptcy substantially declined in Japan during this period).

In contrast, we found that suicide deaths increased by 16% from July to October 2020 (red line in the figure). This finding may not be surprising because the COVID-19 pandemic has affected every aspect of life. In Japan, the unemployment rate has increased for nine consecutive months, social interactions and mobility also have been substantially restricted; fear and anxiety regarding infection are persistent. While the effect appeared with delays of several months, there are a number of factors that could explain our observations.

Lastly, we find that the effects of the pandemic are not evenly distributed across populations. From July to October 2020, the increase in the suicide rate among females (37%) and children and adolescents (49%) were much greater than males (7%). This may be because the pandemic excessively affects female-dominant industries and younger workers, who tend to be low-skilled and non-regular workers. An increase in women’s burdens on childbearing and domestic violence and the stress from unordinary school circumstances could be other factors driving the results.

The reason behind suicide is extremely complex. While our study investigated the effects of the COVID-19 on suicide rate by comparing the observed suicide rate and the plausible counterfactual without COVID-19, we were not able to assess its causes. In fact, it is empirically challenging to evaluate the driving factors in a reliable way. We hope our paper plays an important role in understanding the suicidal effects of pandemic accurately. Also, we hope further research comes out so that we can understand the causes and better design effective preventive strategies.

All the data used in this study is published on our website. Also, the peer-review process is published on our journal’s website. Dr. Okamoto and I appreciate the opportunity to share our findings and the flexible, smooth, and transparent review procedure.

Thank you very much for reading this blog!

Tanaka, T., Okamoto, S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat Hum Behav 5, 229–238 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01042-z

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in