Taking a deep dive into vaccine effects on the respiratory microbiome in Fiji

Published in Microbiology

Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) is a significant global pathogen that can also live harmlessly in the nose of healthy people. In 2011, about one third of the 1.3 million pneumonia deaths in young children were caused by pneumococcus.

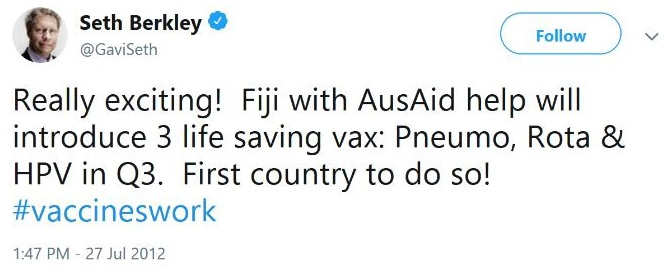

The story behind our paper began over a decade ago with the Fiji Pneumococcal Project, a randomised control trial in Fiji that examined various pneumococcal vaccine schedules. While the population in Fiji is small – around 850,000 people – diseases caused by pneumococci (such as pneumonia and meningitis) are a significant problem. In our vaccine trial, we proved that the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine was effective, ultimately leading to introduction of the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Fiji in 2012.

Our group, based at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, has continued to collaborate with the Fiji Ministry of Health & Medical Services on numerous projects to investigate the burden of invasive pneumococcal disease, pneumococcal carriage, and the impact of vaccine introduction.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines reduce pneumococcal disease as well as pneumococcal carriage. However, they only protect against a subset of the 90+ known pneumococcal serotypes. Following vaccine introduction, carriage of vaccine-serotypes decreases, whereas carriage of serotypes not included in PCVs increases in a phenomenon known as serotype replacement. Knowing that PCV can have ecological effects on pneumococcal colonisation has led us and others to wonder whether PCV possibly has more broad effects on the nasopharyngeal microbiota. We also knew from our previous studies in Fiji that the two main ethnic groups in Fiji – indigenous Fijians (iTaukei) and Fijians of Indian descent (FID) – experience different prevalence of pneumococcal carriage and disease. In a follow-up study, we found that the effects of the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine on bacterial carriage also differed by ethnicity. These observations raised some interesting questions:

- Does pneumococcal conjugate vaccination affect the nasopharyngeal microbiota?

- Do the effects of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination differ depending on ethnic group?

Sample collection in Fiji

We decided to investigate. Our first challenge was determining which samples to use. We conducted cross-sectional carriage surveys before and after PCV10 introduction, however we were concerned that temporal differences and secular trends in bacterial carriage may confound our attempts to investigate vaccine effects. Therefore, we returned to our samples from the original vaccine trial to answer these questions, as nasopharyngeal swabs from vaccinated children and unvaccinated controls had been collected contemporaneously. Fortunately, they had been kept frozen at -80°C with minimal freeze-thaw in the years since the trial finished.

The next challenge was for us to conduct microbiome analyses: despite being experienced microbiologists, we did not have microbiome analysis established in our laboratory. Fortunately, Laura Boelsen, a PhD student with a background in microbiology and a penchant for bioinformatics, was up to the task. Our collaborative team from Australia and Fiji enlisted fellow pneumococcologists and microbiome experts at the Institute for Infectious Diseases in Bern, Switzerland, and Laura visited them for 3 weeks to learn from their experience in microbiome studies of the respiratory tract. Laura returned to Melbourne, conducted the bench work to prepare the samples, liaised with our in-house genomics facility for sequencing, and performed the analysis.

Coat of arms of the City of Bern, Switzerland. Source Wikipedia.

So what did we find? Children who received PCV had a similar microbiota to unvaccinated controls, suggesting that PCV did not affect the nasopharyngeal microbiota overall. The two ethnic groups had distinct differences in microbiota – in both microbial composition and structure. Intriguingly, PCV was associated with different microbiota within each ethnic group – in iTaukei children PCV was associated with lower relative abundance of Streptococcus, and in FID children PCV was associated with higher relative abundance of Dolosigranulum which has been associated with healthy nasopharyngeal microbiota. Ultimately, our observations suggest that PCV has beneficial but differing effects for both ethnic groups, and underscores the public health importance of vaccination.

Follow the Topic

-

Microbiome

This journal hopes to integrate researchers with common scientific objectives across a broad cross-section of sub-disciplines within microbial ecology. It covers studies of microbiomes colonizing humans, animals, plants or the environment, both built and natural or manipulated, as in agriculture.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Harnessing plant microbiomes to improve performance and mechanistic understanding

This is a Cross-Journal Collection with Microbiome, Environmental Microbiome, npj Science of Plants, and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes. Please click here to see the collection page for npj Science of Plants and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes.

Modern agriculture needs to sustainably increase crop productivity while preserving ecosystem health. As soil degradation, climate variability, and diminishing input efficiency continue to threaten agricultural outputs, there is a pressing need to enhance plant performance through ecologically-sound strategies. In this context, plant-associated microbiomes represent a powerful, yet underexploited, resource to improve plant vigor, nutrient acquisition, stress resilience, and overall productivity.

The plant microbiome—comprising bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms inhabiting the rhizosphere, endosphere, and phyllosphere—plays a fundamental role in shaping plant physiology and development. Increasing evidence demonstrates that beneficial microbes mediate key processes such as nutrient solubilization and uptake, hormonal regulation, photosynthetic efficiency, and systemic resistance to (a)biotic stresses. However, to fully harness these capabilities, a mechanistic understanding of the molecular dialogues and functional traits underpinning plant-microbe interactions is essential.

Recent advances in multi-omics technologies, synthetic biology, and high-throughput functional screening have accelerated our ability to dissect these interactions at molecular, cellular, and system levels. Yet, significant challenges remain in translating these mechanistic insights into robust microbiome-based applications for agriculture. Core knowledge gaps include identifying microbial functions that are conserved across environments and hosts, understanding the signaling networks and metabolic exchanges between partners, and predicting microbiome assembly and stability under field conditions.

This Research Topic welcomes Original Research, Reviews, Perspectives, and Meta-analyses that delve into the functional and mechanistic basis of plant-microbiome interactions. We are particularly interested in contributions that integrate molecular microbiology, systems biology, plant physiology, and computational modeling to unravel the mechanisms by which microbial communities enhance plant performance and/or mechanisms employed by plant hosts to assemble beneficial microbiomes. Studies ranging from controlled experimental systems to applied field trials are encouraged, especially those aiming to bridge the gap between fundamental understanding and translational outcomes such as microbial consortia, engineered strains, or microbiome-informed management practices.

Ultimately, this collection aims to advance our ability to rationally design and apply microbiome-based strategies by deepening our mechanistic insight into how plants select beneficial microbiomes and in turn how microbes shape plant health and productivity.

This collection is open for submissions from all authors on the condition that the manuscript falls within both the scope of the collection and the journal it is submitted to.

All submissions in this collection undergo the relevant journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief of the relevant journal. As an open access publication, participating journals levy an article processing fee (Microbiome, Environmental Microbiome). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief of the journal where the article is being submitted.

Collection policies for Microbiome and Environmental Microbiome:

Please refer to this page. Please only submit to one journal, but note authors have the option to transfer to another participating journal following the editors’ recommendation.

Collection policies for npj Science of Plants and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes:

Please refer to npj's Collection policies page for full details.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Microbiome and Reproductive Health

Microbiome is calling for submissions to our Collection on Microbiome and Reproductive Health.

Our understanding of the intricate relationship between the microbiome and reproductive health holds profound translational implications for fertility, pregnancy, and reproductive disorders. To truly advance this field, it is essential to move beyond descriptive and associative studies and focus on mechanistic research that uncovers the functional underpinnings of the host–microbiome interface. Such studies can reveal how microbial communities influence reproductive physiology, including hormonal regulation, immune responses, and overall reproductive health.

Recent advances have highlighted the role of specific bacterial populations in both male and female fertility, as well as their impact on pregnancy outcomes. For example, the vaginal microbiome has been linked to preterm birth, while emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota may modulate reproductive hormone levels. These insights underscore the need for research that explores how and why these microbial influences occur.

Looking ahead, the potential for breakthroughs is immense. Mechanistic studies have the power to drive the development of microbiome-based therapies that address infertility, improve pregnancy outcomes, and reduce the risk of reproductive diseases. Incorporating microbiome analysis into reproductive health assessments could transform clinical practice and, by deepening our understanding of host–microbiome mechanisms, lay the groundwork for personalized medicine in gynecology and obstetrics.

We invite researchers to contribute to this Special Collection on Microbiome and Reproductive Health. Submissions should emphasize functional and mechanistic insights into the host–microbiome relationship. Topics of interest include, but are not limited to:

- Microbiome and infertility

- Vaginal microbiome and pregnancy outcomes

- Gut microbiota and reproductive hormones

- Microbial influences on menstrual health

- Live biotherapeutics and reproductive health interventions

- Microbiome alterations as drivers of reproductive disorders

- Environmental factors shaping the microbiome

- Intergenerational microbiome transmission

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 16, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in