Tentacular team up: Deep partnerships between sea anemones and bacteria

Published in Ecology & Evolution

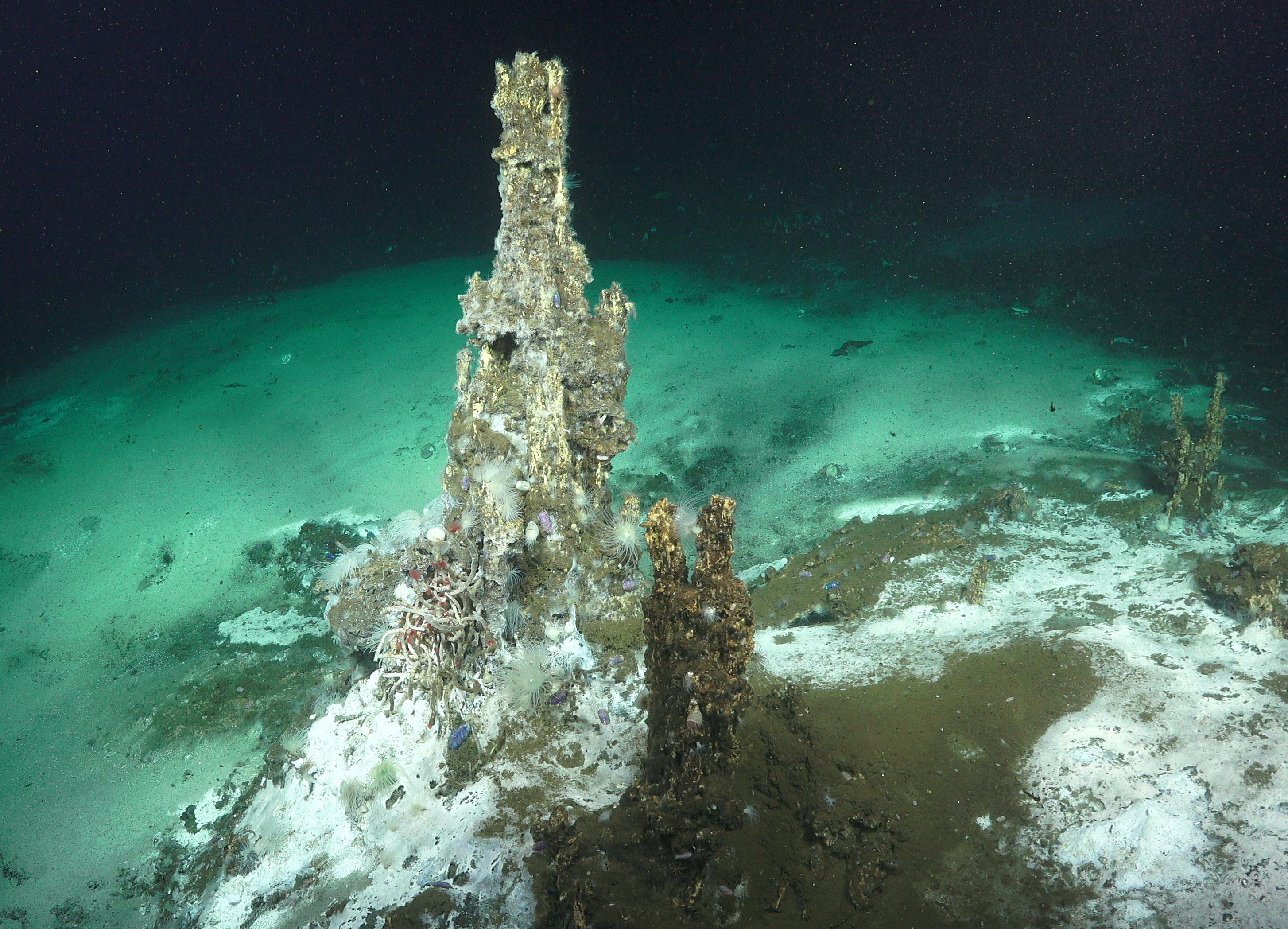

The vast blue surface of the ocean… as far as the eye can see. Far away from the frenetic pace of humans. We have come to a place 80 miles off the coast of La Paz, Mexico to explore what lies beneath this thin ocean skin. In 2018, in collaboration with the Schmidt Ocean Institute (SOI), an interdisciplinary team of geologists, chemists, microbiologists and biologists embarked on a 21-day expedition aboard the R/V Falkor. The biologists on board hoped to witness a fascinating animal community in what is the largest habitat on Earth – the deep sea. Multibeam echosounders, magnetic instruments, and an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) equipped with sonars and seismic sensors were first deployed to gather broad information about the seafloor and form a big picture. Following, a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) named SuBastian, owned by SOI, conducted centimeter-scale resolution mapping using a low altitude survey system, employed for the first time at such deep depths, providing an unprecedented view of the geological and geochemical controls on animal communities at underwater volcanoes, known as hydrothermal vents.

The biologists on our expedition aimed to investigate the density, distribution, diversity, and metabolism of organisms thriving at hydrothermal vents deep in the Pescadero Basin (3700 meters, or ~2.3 miles below). One of these vent fields was discovered in 2012 by scientists using drones that detected thermal anomalies and bottom features consistent with hydrothermal venting. These Pescadero Basin vents in the southernmost Gulf of California differ dramatically from nearby vent fields, most strikingly in their unusual animal communities, with many new species and numerous others found that were not expected to live in the area. Included in this group of unusual fauna was a very abundant white sea anemone that unexpectedly appeared to thrive very near to vigorously venting fluids.

This anemone species, named Ostiactis pearseae, was very abundant, living tucked in between 3-foot tall tubeworms and sulfide-oxidizing clams. Anemones normally capture either large prey using stinging harpoons or small particles suspended in seawater using sticky tentacles. Neither of these strategies appeared to be the primary mode of dining by O. pearseae. Further, we knew from past studies that animals in the areas of highest volcanic activity usually take advantage of chemical energy for their sustenance, rather than energy from the overlying sunlit ocean far above. Incredibly, as we detail in our recent paper published Jan 18, 2021 in BMC Biology, this anemone receives nutrition from bacteria living inside of their skin cells, that use the chemical compound hydrogen sulfide to fuel organic carbon production. This trick is all the more strange given that other related reef-building corals and anemones house symbionts in their digestive system, on the outside of their cells. Our understanding of this phenomenon was made possible by a collaboration among an international science team involving undergraduates and science faculty from both a small liberal arts college and several research universities, as well as scientists at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. We are very excited to revisit this site in October 2021 to explore unanswered questions about this extreme alliance between marine invertebrates and beneficial bacteria.

- Shana Goffredi (Occidental College) and Allison Miller (Schmidt Ocean Institute)

Photos copyright SOI. Contact sgoffredi at oxy.edu with questions or further inquiries about this work.

Goffredi, S.K., Motooka, C., Fike, D.A. et al. Mixotrophic chemosynthesis in a deep-sea anemone from hydrothermal vents in the Pescadero Basin, Gulf of California. BMC Biol 19, 8 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-020-00921-1

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Biology

This is an open access journal publishing outstanding research in all areas of biology, with a publication policy that combines selection for broad interest and importance with a commitment to serving authors well.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Small RNA structure and regulation

BMC Biology is calling for submissions for the Collection on small RNA structure and regulation. Small RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), piwi interacting small RNAs and tRNA-derived small RNAs are crucial regulators of gene expression in a variety of biological processes. These short, non-coding RNAs play a significant role in transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation, influencing pathways that govern development, differentiation, and cellular responses to environmental stimuli. As they are involved in the modulation of gene silencing and regulatory networks, understanding their structure and function is essential for elucidating their contributions to cellular homeostasis, host-microbe interactions, and disease.

Research in small RNA biology has made significant strides in recent years, unraveling the complexities of small RNA pathways, their biogenesis and their regulatory functions across different species. Advances in multiple cutting-edge technologies, including high-throughput sequencing, massively parallel enzymatic assays, Cryo-EM, and computational tools such as artificial intelligence, have facilitated the identification and characterization of novel small RNAs across diverse organisms. These technologies have also enabled the exploration of detailed and exciting mechanisms of small RNA pathways at cellular, molecular, and atomic levels on a large scale. Furthermore, studies on miRNA functions in various cellular and organismal contexts have deepened our understanding of their roles in health and disease. These developments underscore the importance of continued research into small RNA mechanisms to unlock their therapeutic potential.

As research in this field progresses, we anticipate breakthroughs that could revolutionize our understanding of regulation of gene expression involving small RNAs. Future studies may uncover novel small RNA species, elucidate their roles in complex regulatory networks, and inform innovative therapeutic strategies for diseases linked to dysregulated small RNA pathways.

Potential topics for submission include, but are not limited to:

Mechanisms of small RNAs biogenesis

Structural insights into small RNAs

Epigenetic modifications regulating small RNAs

Functional genomics of small RNAs

Roles of RNA-binding proteins in shaping small RNA function

Mechanisms of miRNA and siRNA regulation

Cross-talk between different small RNA pathways

Gene expression regulatory networks involving small RNAs

Advanced methods for small RNA sequencing, analysis and gene target prediction

Extracellular small RNAs: secretion mechanisms and potential functions

Therapeutic potential and applications of small RNA

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 04, 2026

Human microbiome in health and disease

BMC Biology is calling for submissions on our Collection on Human microbiome in health and disease. The human microbiome plays a crucial role in maintaining health. Comprising trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea, the microbiome influences various physiological processes, such as metabolism, immune function, and even mental health through pathways like the gut-brain axis. Recent advances in sequencing technologies and bioinformatics have enabled researchers to explore the intricate relationships between the microbiome and human health, revealing its potential as a target for therapeutic interventions.

Continuing to advance our understanding of the human microbiome is essential for developing novel strategies to prevent and treat diseases. Significant progress has been made in identifying specific microbial signatures associated with conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and cancer, as well as understanding the impact of antibiotics on microbial diversity. These insights have opened new avenues for personalized medicine, where microbiome profiling could guide treatment decisions and improve patient outcomes.

As research in this field progresses, we can anticipate exciting developments, including the potential for microbiome-based therapies, such as probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation, to become mainstream treatments. Furthermore, ongoing studies may uncover the role of the microbiome in modulating responses to immunotherapy in cancer patients, leading to more effective and tailored treatment approaches.

Potential topics for submission include, but are not limited to:

The role of the gut, oral, skin, and vaginal microbiome in health and disease

Microbial ecosystems and their impact on the immune system

The gut-brain axis: implications for mental health

The connection between the microbiome and neurodegenerative diseases

Evolution of the human microbiome across different populations

Effects of antibiotics on microbiome diversity

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being.

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in