The Hidden Guests: Rethinking the Tumor as a Microbial Landscape

Published in Cancer

The story of cancer has long been a solitary one.

A single cell, gone rogue. A mutation, silent and then irrepressible. An empire of copies, spreading by division, unchecked by the laws that once governed it. From microscope to molecular map, we have trained our gaze inward, toward the human nucleus, the human gene, the human signature of malignancy.

But every story has its margins. And for more than a century, something has stirred at the edges of the cancer narrative—a whisper that perhaps the tumor is not a fortress of human failure alone. Perhaps, within its folds, there are others.

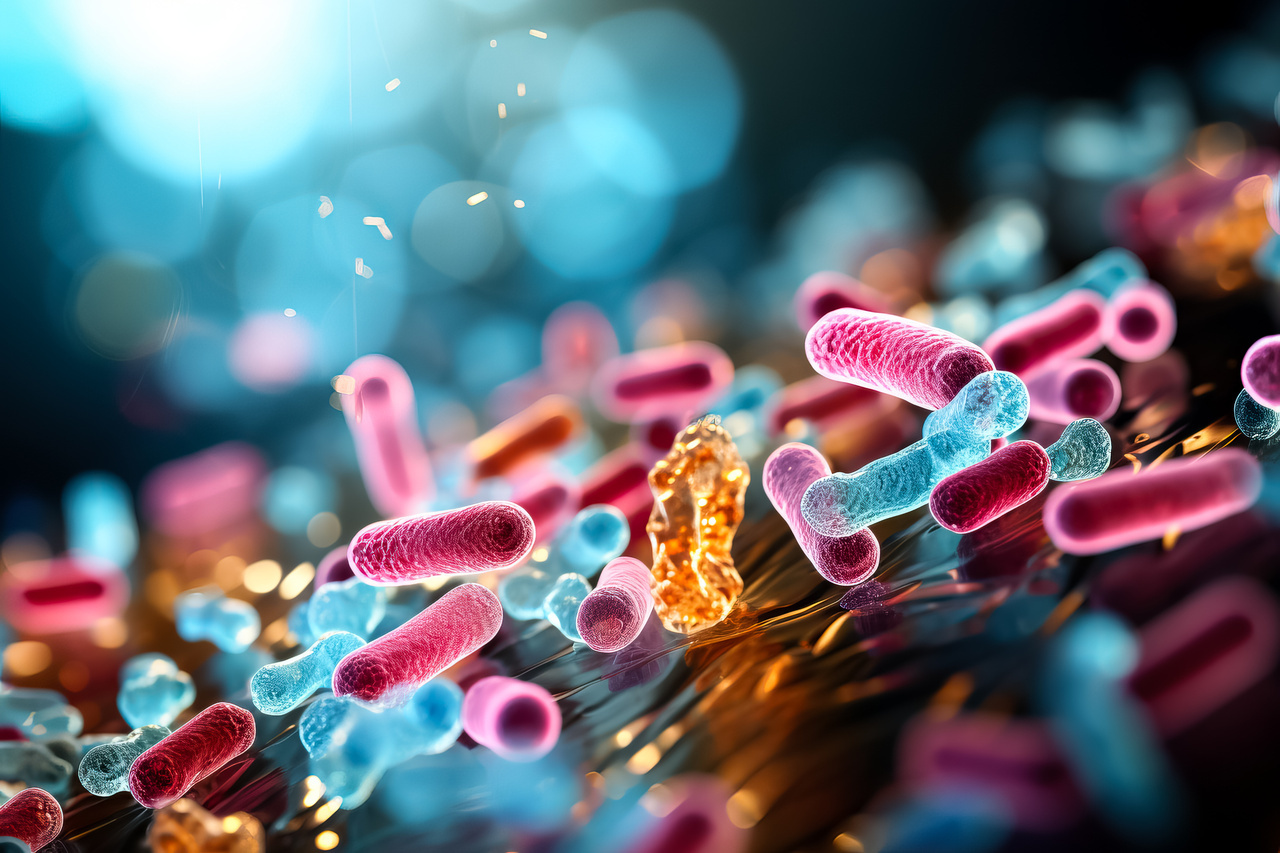

In 2020, a team led by Ravid Straussman published a finding in Science that startled even those attuned to the unexpected: bacteria, nestled not around tumors, but within them. From breast to lung to pancreatic cancers, bacterial DNA, and in some cases live microbes, were identified deep in the tumor microenvironment. Not surface contamination. Not circulating debris. Residents.

The idea wasn’t entirely new. As early as the 19th century, William Coley had noticed that patients whose tumors became infected sometimes improved. He began injecting sarcomas with live bacteria in the hope of igniting immune rejection. The technique was crude. The results inconsistent. But in retrospect, his intuition was almost clairvoyant: that microbes could shape the immune system’s response to cancer.

For most of the 20th century, such thoughts faded into the background. Cancer was internal, human, a problem of genes and the cells that carried them. The body’s microbial inhabitants were either benign bystanders or dangerous intruders, but never central to the malignant process. We studied cancer as if it were sterile.

But the human body is not sterile. It is a densely populated terrain of microbial life—on the skin, in the gut, and now, we are learning, in tumors. Not all cancers carry the same microbes. Breast tumors appear to host different bacterial communities than pancreatic or colorectal cancers. Some bacteria seem to protect, others to disarm chemotherapy, still others to awaken immunity. Their effects are not fixed. They depend on context—on the type of cancer, the architecture of the tissue, the state of the immune system, and the drugs being used.

In one study, certain pancreatic tumors harbored bacteria capable of degrading gemcitabine, rendering the drug ineffective. In another, specific microbial signatures predicted better response to immunotherapy. The tumor microbiome, like its intestinal cousin, is neither hero nor villain. It is a participant.

Researchers like Susan Bullman, Jennifer Wargo, and Ami Bhatt are now trying to map this invisible world with molecular precision. Using spatial transcriptomics and advanced imaging, they are asking not just what microbes are present in a tumor, but where they are—and what they touch. A bacterium adjacent to a cancer cell might influence proliferation. One nestled beside a dendritic cell might shape antigen presentation. Proximity becomes influence.

This vision of the tumor—as a densely layered ecosystem—invites a radical reframing. Cancer, we now understand, is not simply a rebellion of our own cells, but a transformation of the local environment. That environment includes oxygen levels, blood flow, immune traffic, and now, microbial guests.

The implications are profound. Could microbial profiles help us diagnose cancers earlier? Might we tailor treatments not just to a tumor’s genetics, but to its microbial landscape? Could manipulating the tumor microbiome make stubborn cancers more responsive to immunotherapy?

The tumor has never been truly alone. And perhaps that is the deeper lesson. That in our effort to decode cancer’s cellular language, we may have missed a dialect spoken not by us, but by our microbial companions. Bacteria, long cast as intruders, may be co-authors in the script of malignancy.

In this evolving story, the margins are becoming the center. And the tumor, once imagined as a fortress of solitude, is beginning to resemble a crowded, conflicted city—its fate shaped not by the cell alone, but by all who dwell within.

Follow the Topic

Ask the Editor – Inflammation, Metastasis, Cancer Microenvironment and Tumour Immunology

Got a question for the editor about inflammation, metastasis, or tumour immunology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in