The hidden volcanoes of the northern Reykjanes Ridge

Published in Earth & Environment

When people think of Icelandic volcanism, they often picture glowing lava fountains, fissure eruptions, and lava flows like those seen during the recent eruptions on the Reykjanes Peninsula. Since 2021, this region has experienced a sequence of eruptions that have been broadcast worldwide, marking the likely onset of a new eruptive episode that may continue for decades. The last time Iceland experienced a comparable period of sustained activity on the Reykjanes Peninsula, it was known as the Reykjanes Fires, recorded by early settlers more than eight centuries ago.

The recent eruptions are largely effusive, producing lava flows that advance relatively slowly but nonetheless pose a serious challenge to infrastructure and nearby communities. At the same time, they have provided a rare opportunity for scientists. Over the past few years, these eruptions have been studied in exceptional detail, leading to major advances in our understanding of how magma is supplied, stored, and transported within the Reykjanes magmatic system.

But volcanism does not stop at the coastline.

If you stand at the southwestern tip of the Reykjanes Peninsula and look toward the open ocean, the volcanically active Reykjanes Ridge continues for several hundred kilometers beneath the sea surface. There, it forms part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the vast plate boundary that separates the North and South American plates from the Eurasian and African plates. Unlike eruptions on land, volcanic activity along these submerged ridges is extremely difficult to observe directly, and much of it remains out of sight and out of reach. As a result, comparatively little research has been conducted offshore, and eruptions along this section of the ridge have long been assumed to be mostly effusive, resembling the typical mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) volcanism observed elsewhere on the global ridge system.

Figure 1: At the southwestern tip of the Reykjanes Peninsula, the Reykjanes Ridge approaches land before continuing offshore beneath the North Atlantic. This onshore–offshore transition provides a unique natural laboratory for studying how eruptive styles vary with water depth along an active mid-ocean ridge. Photo: Jonas Preine.

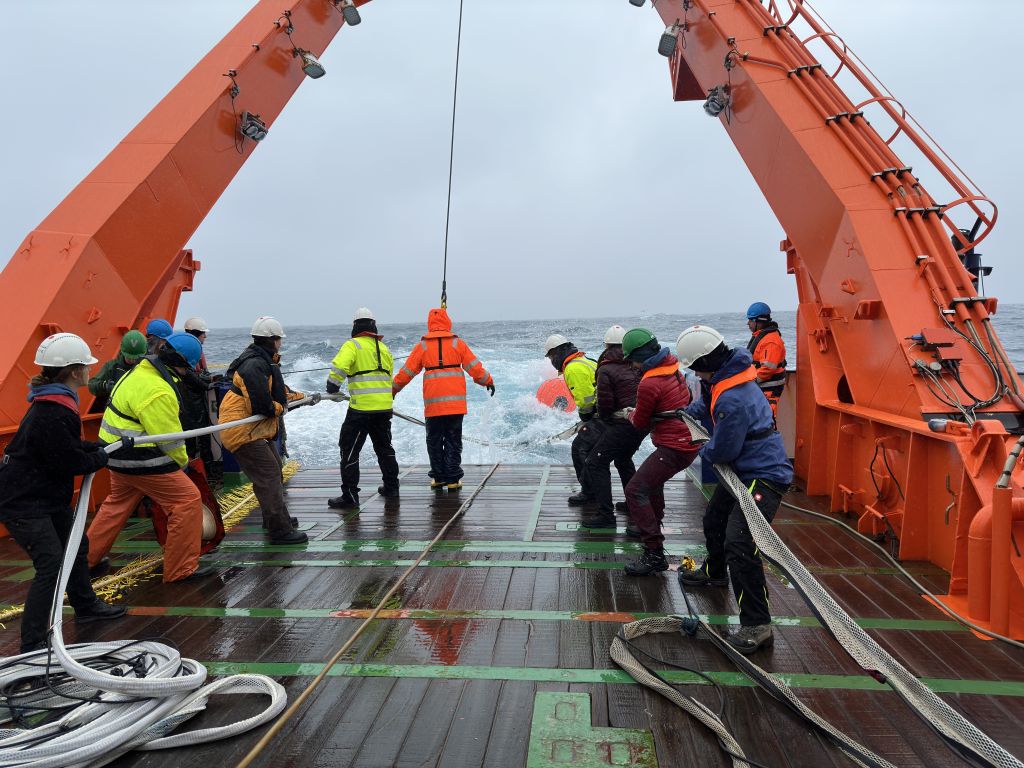

In the summer of 2024, an international team of researchers from the University of Hamburg, GEOMAR, the University of Gdańsk, King Abdullah University for Science and Technology, Oregon State University and the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute in Hafnarfjörður set out aboard the research vessel RV Meteor to investigate offshore volcanic systems west of Iceland. The primary goal of the expedition was to study the Vesturdjúp Basin, far offshore, using seismic reflection profiling, seafloor sampling and seafloor imaging.

To calibrate our seismic system and test the survey setup, we collected two seismic profiles across the Reykjanes Ridge. These profiles crossed the ridge axis at different latitudes and water depths — and revealed a striking contrast.

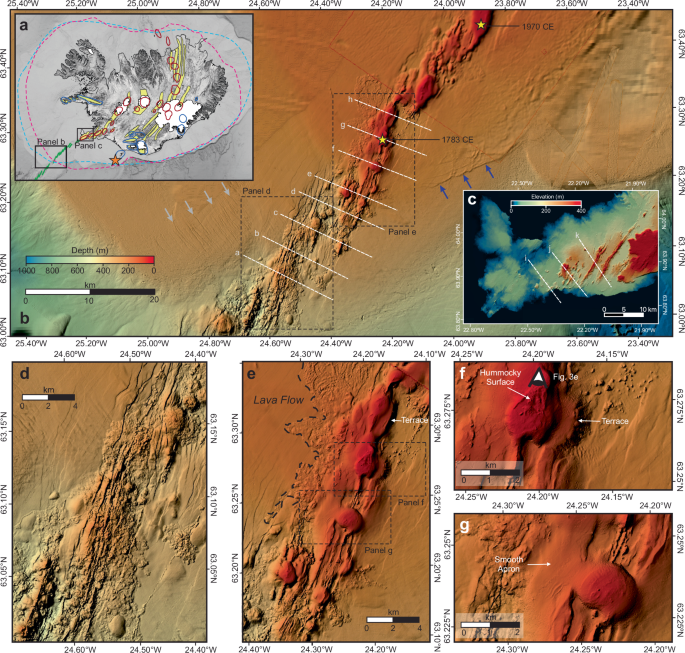

The northern profile, crossing the ridge north of ~63°N at water depths of roughly 300 m, imaged volcanic edifices with layered, outward-dipping flanks surrounding acoustically chaotic to transparent cores. This internal architecture is difficult to reconcile with construction by coherent lava flows alone. Instead, it closely resembles the seismic signature of volcaniclastic-dominated volcanoes, built largely from fragmented volcanic material produced by explosive eruptions. Similar architectures were known to us from other volcanic settings where explosive activity has been independently confirmed by drilling and seafloor observations.

In contrast, the southern profile, crossing the ridge farther south at greater water depths, imaged volcanic edifices characterized by chaotic, highly attenuating seismic facies consistent with dense, lava-dominated construction typical of MORB volcanism along mid-ocean ridges. Here, eruptive activity appears largely effusive, in line with long-standing expectations.

Together, these observations pointed to a fundamental change in eruptive style along the Reykjanes Ridge axis.

Figure 2: The science team of Expedition M201 on deck of RV Meteor deploying seismic reflection equipment to image the internal structure of volcanic edifices along the Reykjanes Ridge. Photo: Oliver Eisermann.

Motivated by this discovery, we conducted additional seismic profiling and seafloor imaging along the northern Reykjanes Ridge. These follow-up data confirmed that the volcaniclastic-dominated structures were not isolated features, but part of a broader volcanic style restricted to the shallowest segments of the ridge.

By combining seismic imaging with seafloor observations, our study shows that explosive shallow submarine volcanism is far more common along the Reykjanes Ridge than previously recognized. Importantly, we identify a clear transition in eruptive style around ~63.2°N, coinciding with water depths of approximately 300 m. South of this boundary, volcanism is dominated by effusive MORB-style eruptions. North of it, explosive volcanism becomes increasingly important, producing volcaniclastic edifices that remain entirely submarine but are built in a manner strikingly similar to shallow-water explosive systems.

Figure 3: Overview of Expedition M201 aboard RV Meteor. Upper left: RV Meteor approaching Reykjavík. Upper right: Deployment of seismic reflection equipment. Lower left: Deployment of the Ocean Floor Observation System (OFOS) for seafloor imaging. Lower right: Onboard processing and first interpretation of seismic data. Photos: Vanessa Ehlies, Oliver Eisermann, Benedikt Haimerl, Jonas Preine.

At this point, a natural comparison emerges: Surtsey.

Surtsey formed during a 1963 eruption in the marine part of the Eastern Volcanic Zone of Iceland, when magma rising from the seafloor reached very shallow water and suddenly came into contact with the ocean. Each interaction between hot magma and cold seawater triggered violent explosions, fragmenting the magma into ash and rapidly building a new volcanic island that grew visibly from day to day. At the time, Surtsey was seen as a remarkable but unusual event, largely because it occurred off-axis and outside the main mid-ocean ridge system. Our findings suggest that the processes observed at Surtsey also operate along the Reykjanes Ridge, where similar magma–water interactions can occur beneath the ocean surface.

Figure 4: Surtseyan eruption at Surtsey, Iceland, on 30 November 1963, shortly after the onset of volcanic activity. The interaction between rising magma and shallow seawater led to intense explosive fragmentation and the rapid construction of a volcanic island. Surtsey formed in the Eastern Volcanic Zone of Iceland and has long been considered a special case of explosive submarine volcanism. Our findings suggest that similar explosive eruptions may have occurred repeatedly along the Reykjanes Ridge. Photo: Howell Williams / NOAA (public domain).

Historical observations support this idea. Written records and anecdotal reports describe the temporary emergence of volcanic islands along the Reykjanes Ridge, such as Nýey, which appeared briefly in the late 18th century before being eroded below sea level. Such rapid disappearance is consistent with edifices constructed largely from volcaniclastic material, which is mechanically weaker and far more susceptible to wave erosion and marine reworking than coherent lava flows. In contrast, islands built predominantly by effusive eruptions tend to be more resistant to erosion and are therefore more likely to persist.

The implications extend beyond Iceland. If explosive volcanism can occur systematically along shallow sections of mid-ocean ridges, then volcaniclastic deposits may be far more widespread on the seafloor than currently mapped. Such deposits are difficult to recognize without seismic imaging and are easily misinterpreted. This affects how we interpret marine sedimentary records, how we estimate volcanic material and volatile fluxes into the ocean, and how we assess volcanic hazards in regions where submarine eruptions could rapidly shoal or even breach the sea surface.

More broadly, our findings challenge the long-standing paradigm that mid-ocean ridge volcanism is almost exclusively effusive. Instead, they suggest that explosive eruptions represent an important component of oceanic volcanism - given the right water depth.

Dr. Jonas Preine

Postdoctoral Scholar at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Climate extremes and water-food systems

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in