The Problem of Personal Responsibility Narratives

Published in Social Sciences and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

When I was growing up, the available ways of understanding the world around me were mostly about personal responsibility. That is, if I wanted to make anything of my life I would need to work hard, and make it happen. And though it’s not untrue, effort matters in a lot of things, it is incomplete: There are plenty of people whose excellent work goes unrewarded, or who never have a chance to show what they are capable of, or by contrast, who glide through life without working much at all. The existence of those people is inconsistent with a personal responsibility narrative, and so, without some self-reflection or mental effort, you can sweep those exceptions out of your mind easily. Some of the classic work in social psychology (and my own early work) is about these dynamics.

I return to personal responsibility logics again and again in my scholarship because of how pervasive they are. Now, it is perhaps most important to combat these narratives, as state repression rises and our institutions work to punish people for writing opeds, or being brown, or for protesting. Personal responsibility narratives in this context can act as a cover for fascism: If only they would have not said those things, obeyed harder, paid more money, or bowed lower.

In the study of psychology, there is an awful lot of evidence of personal responsibility narratives in findings and insights from research. If you want to be happy, you spend money on experiences. If you want to accomplish your goals, form these habits. If you want to experience lower levels of stress, be more mindful. If you want to have more committed relationships, sacrifice more. All of these insights come from psychological studies conducted over the past decades. Implied in all of them is that people’s behavior controls their happiness, goal achievement, stress, and relationship satisfaction. In this fashion, psychology as a field is often involved in propping up these kinds of personal responsibility logics about society. Bad outcomes are the result of bad decisions or behaviors.

In academic fields, we also do business in ways that apply these personal responsibility logics. Awards and other desired outcomes are often influenced by citation counts, journal prestige, and institutional affiliations. Grants are judged based on whether a scholar has the equipment and support from their institution that would be necessary to carry out the scholarship. Tenure and promotion decisions sometimes ask for comparisons with other scholars at peer institutions but do not explicitly draw attention to how two scholars might differentially experience teaching, parenting, or scholarship based on their identities, available support, and the like. Zooming out to society, we see similar logics. According to our legal system, people are responsible for their own crimes—not the conditions that disproportionately target them. It is personal responsibility all the way down.

In this context we can see how easy it is to go along with personal responsibility narratives, and conversely, how effortful it can be to reject these logics. It feels hard to do so personally, because it can be threatening to admit that I am here not on account of my own effort, or that whole educational institutions, museums, and entire cities are under attack from our government. It can also be hard to do it as a part of your scholarship because much of our research methodology and training in psychology theorizes about and models personal responsibility. We are incentivized to write about the implications of our work, and sometimes that writing makes the case for individuals as personally responsible for their life outcomes in absence of other factors.

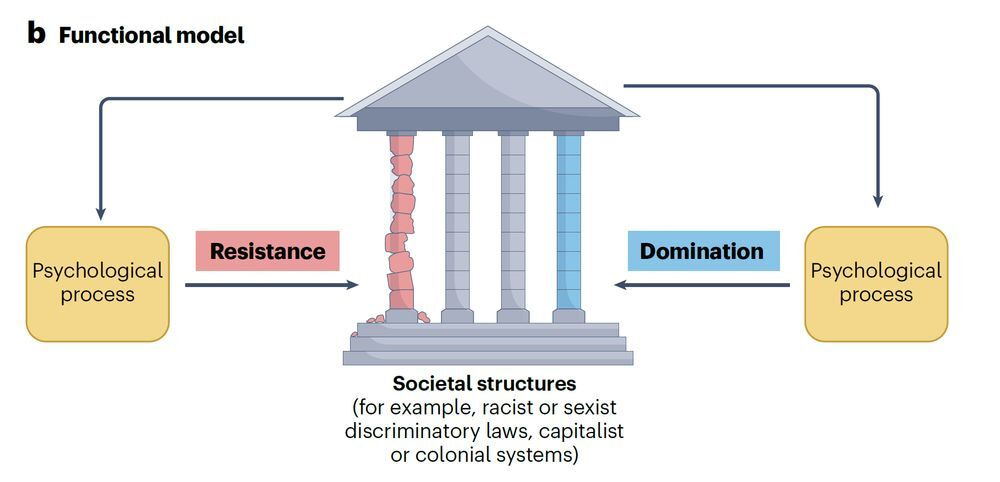

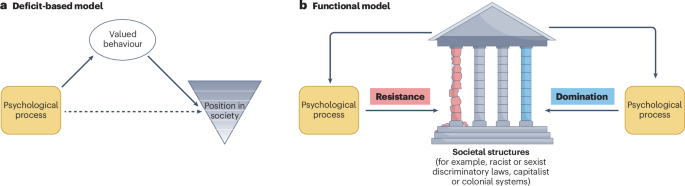

So, our lab wrote this paper to articulate how researchers might more fully reject personal responsibility explanations for inequality (we call them deficit models in the paper) in research within psychology. We center our analysis on the fundamental truth of societal structures of domination. That is structures (like racism, capitalism, ableism, sexism) designed, erected, and maintained to keep things unequal. We argue that studying these structures (e.g., how they are created, maintained, and dismantled) is how psychologists could more fully move beyond personal responsibility explanations for inequality. Fundamentally, focusing on how structures dominate people asks us to start in an entirely unique analytic space to most psychology research: Instead of studying how and why individuals end up sorted into societal positions, we ask why structures keep them where they are and how our psychology works for or against that process.

The amazing news is that there is already research that approaches inequality in this fashion—examining structures of domination and psychology’s role within it. And throughout the paper we draw from those insights, mostly to give credit where it’s due, but also to point out that studying structures of inequality is possible, necessary, and already happening within our discipline. This paper on how police stops might make people more likely to commit crimes is one great example. This paper on how factory workers participate in an experiment where they make decisions for themselves and that leads them to become more broadly politically active is another!

It might strike you as hard to name, study, and work to dismantle structures of domination in scholarship moving forward. And there are good reasons to be concerned: At best incentives to do this kind of work are below what they have been (and those incentives weren’t all that high to begin with). Nevertheless, work that challenges personal responsibility narratives is always crucial, because bad things happen to good people all the time.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Reviews Psychology

An online-only journal publishing authoritative, accessible and topical Review, Perspective and Comment articles across the entire spectrum of psychological science, its applications and its wider societal implications.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in