The rise of preprints in biological sciences

Published in Chemistry

The way we do scientific research today is drastically different from the way we did it in 1997 when I started my undergraduate study. No more do we have to endure the wait for internet over the irritating dial-up sound. Few now go to libraries to make copies of journal articles using a coin-operated photocopier, or read articles using a microfilm machine. In fact, many libraries barely have a book in sight.

More importantly, the open-access movement is revolutionizing the way we do research. This drastically reduced the times when we try to access a seemingly exciting research article only to be put off by a subscription paywall, when we email (or mail, back in the day) the corresponding author to request a reprint, and/or when we ask our colleague at a different university (for which the library happens to subscribe to the journal of interest) to download the article for us. For authors, by paying for the article processing charges and making their research freely available, the exposure of their research is maximised, thus their work is more likely to get cited.

Given the increased accessibility to up-to-date literature driven by the open-access movement, one may imagine that we are in a much better position to do high-quality research, therefore the quality of research publications we come across would be higher too. Unfortunately, this has not always been the case.

The rise of predatory publishers is one of the inconvenient side-effects driven by the open-access movement. Many of us will have received invitations to contribute to open-access journals we have never heard of, and in many occasions, in areas that are not even remotely related to our areas of expertise. These journals, just like predatory conferences, make money by taking advantage of the user-pay system; some have titles and websites that resemble known, reputable journals in the discipline. If submissions to these journals are indeed peer-reviewed as they claim to be, I sometimes wonder why I have never received invitations to review any of their submissions.

The publication process can be tedious and slow. Some authors would hop from one journal to another after a rejection (and repeat if necessary). Some submissions may involve an excruciatingly long reviewing process that goes on for months or even years. In many cases, new ideas or data are simply sitting idle during this process, and become stale by the time they are published; this undoubtedly slows down research progress. For this reason, preprint servers, designed to make research manuscripts immediately and freely available before the peer-review process, have become an attractive option.

In an attempt to make our data immediately available for the research community, we deposited our earlier work on the genomes of coral reef symbionts on the bioRχiv preprint server. This work (after rounds of revisions) was eventually published about nine months later in the open-access journal of Communications Biology (see also here), at which point our data had already been used in other studies, and the preprint article had garnered two citations.

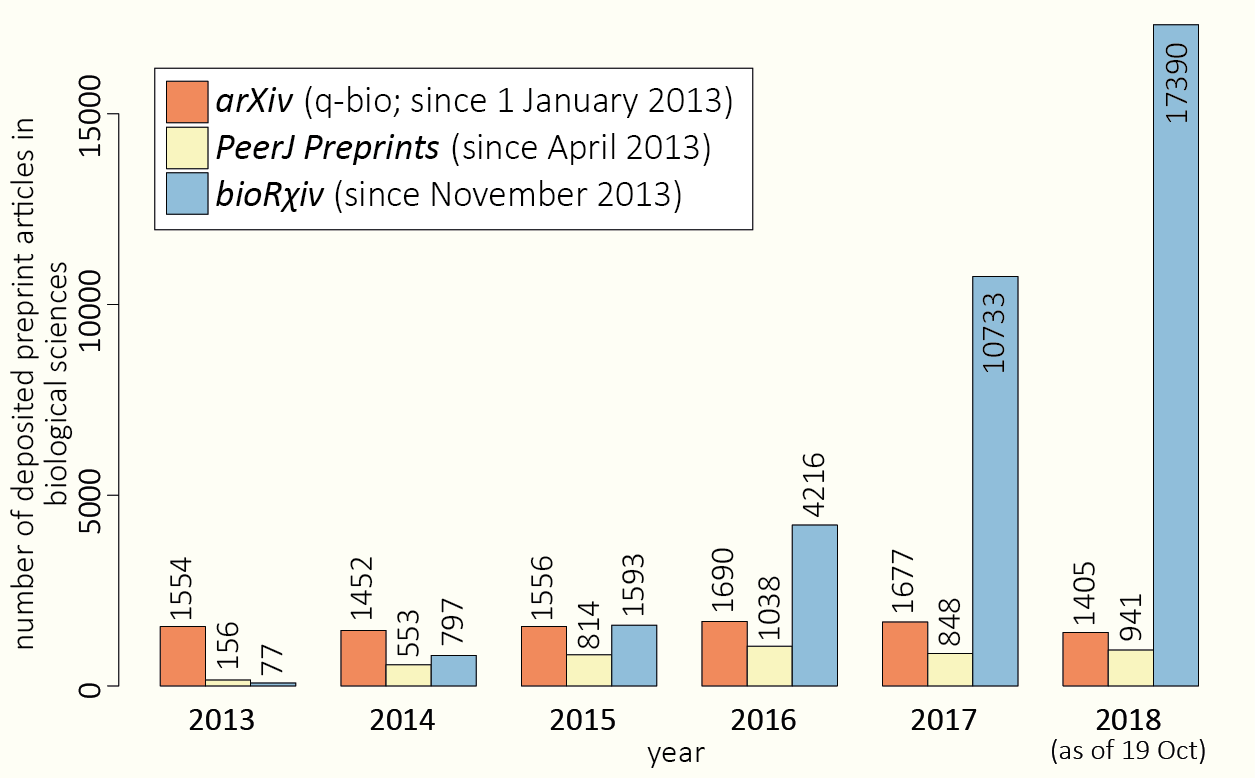

The practice of depositing manuscripts on preprint servers prior to submission to a journal is relatively new in the life sciences community, but it is by no means a new research practice. The arΧiv.org preprint server at Cornell University, initially set up as a physics archive, was launched back in 1991. They have a q-bio (quantitative biology) track, for which I deposited three research manuscripts from my earlier PhD work on microbial genomics (in 2007); all were subsequently published in journals. PeerJ Preprints and bioRχiv servers, both dedicated to biological sciences, were established later in 2013.

Based on the number of deposited preprints of biological sciences in each of these servers over the same period (2013-2018; below), it is clear that researchers in the life sciences community are increasingly adopting the practice of preprint deposition to set precedence of their work, and to make their work immediately available. The exponential growth of the number of bioRχiv preprints suggests that the bioRχiv is becoming the server of choice within the community.

So, biologists are more inclined to share their data and make their work open-access. This is encouraging against the backdrop of other non-conventional publication models, such as F1000Research that encourages publications of any solid research reporting, e.g. negative findings and case histories "that are currently shunned by many journals", and Biology Direct that publishes reviewers’ comments and authors’ rejoinders alongside the final, accepted paper.

On the other hand, Peer Community In … is a recent initiative set up by peers working in a specified discipline to evaluate and recommend preprint articles that have been deposited in any open repositories. For those leading to a recommendation, the reviews and the authors’ responses are published online. PCI Evolutionary Biology, launched in January 2017, brings together some of the most eminent researchers in the field. A recommended preprint article may still be submitted to a journal for publication. This peer-reviewed preprint, however, would have been improved from the original article, and thus stands a better chance of getting accepted for publication in a journal. I hope that the PCI initiative will expand from the current three communities (Evolutionary Biology, Ecology and Paleontology) to include other disciplines soon.

Certainly, to find a good home for our research work, open-access or not, preprint first or not, we would still consider the reputation and readership of a journal, and the quality of the expert reviews and editorial process (including speed). Ideally, we want to receive high-quality, constructive reviews that would help us in improving our work prior to publication. Funding agencies and universities should put less emphasis on journal impact factor and more on individual article metrics and research quality in the assessment of a researcher’s track record. While some funding agencies require outputs of the research they fund to be made open-access, they should consider a special allocation for article processing charges. If you are a well-funded and prolific author, you can easily spend over USD 60000 a year to pay for the 30 open-access articles you publish but have no allocation in your grant to pay for it due to expenditure limitations; this amount is not exactly small.

Last week, I received another rejection email on one of our manuscripts. This week, I learned from my collaborators that some of the sequencing data we generated may be utterly rubbish. "Life goes on", I say to my students. While our research interest is to understand the resilience of coral reefs in the light of global climate change, we too, need to learn to be resilient to adversities. At least for the latter, we won’t need to study our genomes to know what to do – we persevere and never give up.

This post was first published on the Nature Research Ecology & Evolution Community.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in