Editor’s note: the January 2015 issue of Nature Chemistry features a Thesis article ($) from Michelle Francl that looks at chemists’ fascination with benzene. It is illustrated with a range of different representations of benzene and benzene-containing compounds drawn by Michelle’s own fair hand. Here is a short accompanying blog post by Michelle, including a quiz!

I’m teaching the first year course in chemistry this fall, and in addition to making certain my students have a firm grasp on Hess’ law, VSEPR theory, and gases, I’ve been insisting they learn to draw. To think like chemists, I tell them, and to keep from drowning in later organic chemistry lectures, they need to be able to quickly draw chemical structures that other chemists can ‘read’ and to see in their own heads the reality these particular embeddings represent. So we learn the chemical alphabet, wedges and dashes, chairs and boats — and the iconic hexagon.

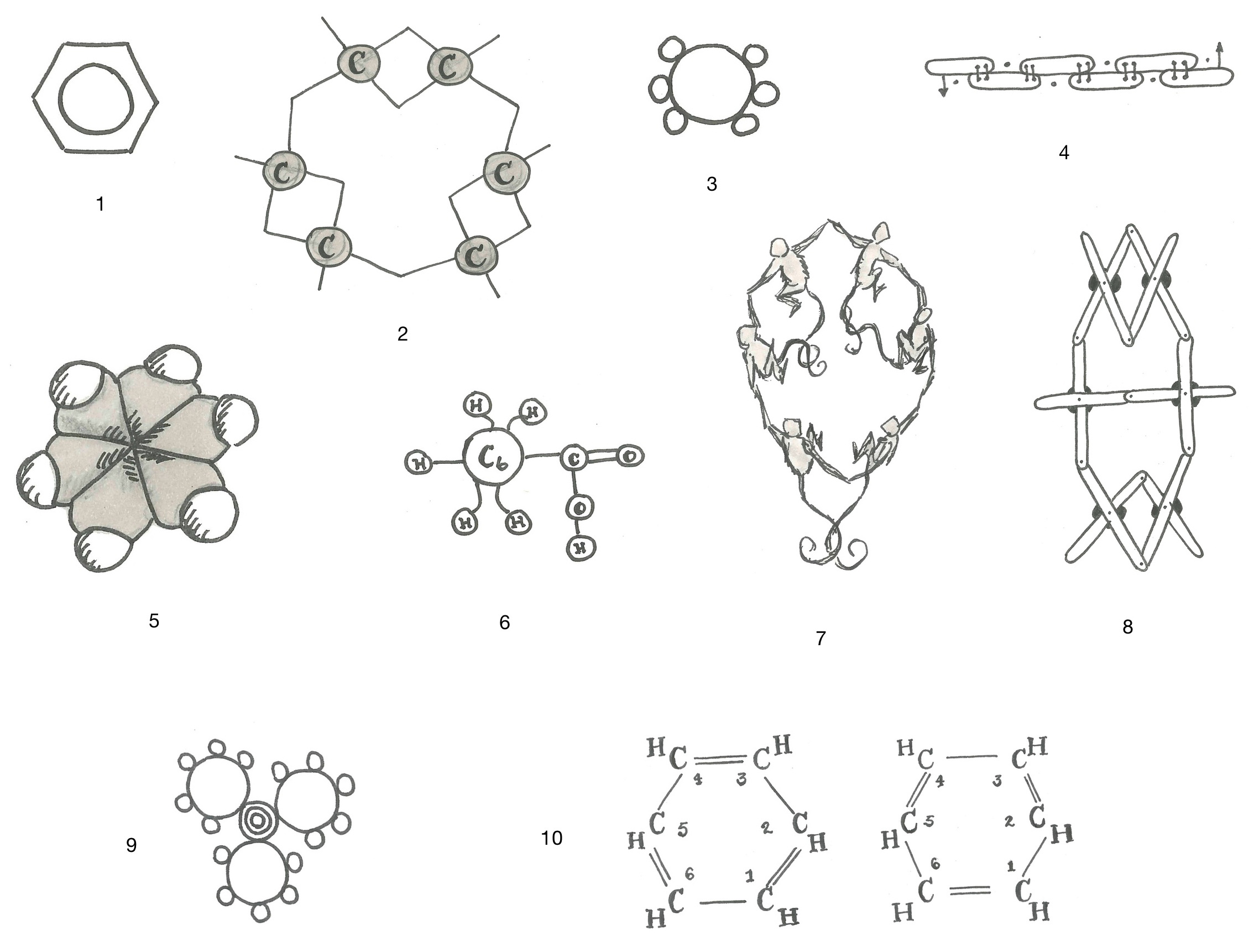

It took chemists more than 100 years after Michael Faraday isolated and characterized benzene to settle on the hexagon with a circle in the center as a convenient way to represent the hexavalent kernel of organic chemistry. I found more than a dozen different representations of benzene in the chemical literature, Kekulé alone used three types, and like the Buddhist wisdom tale of the elephant and the blind men, each attempt brought out a different facet of the structure and bonding. Can you match each of the structures (1-10) with its description (A-J)?

A. Alexander Crum-Brown’s 1866 representation of benzoic acid.

B. From a Liebigs Ann. Chem. paper published by August Kekulé in 1872.

C. Appeared in 1886 in Berichte der Dürstigen Chemischen Gesellschaft (Reports of the Thirsty Chemical Society) a spoof edition of Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft.

D. From Kekulé’s first paper suggesting that benzene was a circle (published in 1865).

E. From an 1861 pamphlet published by Johann Loschmidt.

F. James Dewar’s contraption for representing molecular structure, illustrating an isomer of benzene, the inspiration for ‘Dewar benzene’. Despite legends to the contrary, Dewar does not suggest the structure in his 1867 paper as an alternate bonding scheme for benzene, the paper is about building the brass pieces to use to make molecular models.

G. From a paper published by Robert Robinson and James Armit in 1925. Armit etched it into the window of his family’s bakery in St. Andrews, Scotland.

H. In August Kekulé’s 1867 Lehrbuch der organischen Chemie (Textbook of Organic Chemistry).

I. A representation of benzene following the style used in a paper published by Cox, Cruickshank and Smith in 1958.

J. Triphenylamine in Loschmidt’s notation (from the same 1861 pamphlet as E).

Editor’s note: post your answers as a comment here, or on Twitter (mentioning @NatureChemistry), in the form 1A, 2B, 3C, 4D, etc… no prizes, apart from kudos and some retweets.

Editor’s note Jan 9th, 2015 – the correct answers are: 1G, 2H, 3E, 4D, 5I, 6A, 7C, 8F, 9J, 10B. The first person to get them all right was Stephen Davey (his second guess in the comments). Steve does, admittedly, work at Nature Chemistry, but before you all groan and roll your eyes, he had no way of finding the answers (that was all between Michelle and myself). You’ll see that Cristiano Zonta also got all the answers right and it is worth noting that his and Steve’s blog comments were both moderated (by me) at the same time, so even though Steve’s comment was first, Cristiano could not have seen these answers before posting his own identical ones (because both blog comments were published at the same time). With 8/10, @fxcoudert and @samofthedamned also get honourable mentions – and thanks to everyone else who played along on Twitter. Apologies if I’ve missed any other high-scoring guesses.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in