Thinking about electricity systems for the future

Published in Social Sciences

Renewable generation is essential to staying within the world’s carbon budget. Many renewable generation technologies are commercially viable and in extensive use today, yet concerns remain about maintaining a stable flow of electricity from intermittent renewable resources. Demand-side response is one of many potential tools to address this problem - by using price signals, electricity users can be nudged into shifting their electricity demands to times when supply is readily available, reducing problems with grid stability.

However, price signals won’t have an equivalent impact on everyone. Energy poverty, whereby people face challenges meeting both energy and other necessary costs such as food and medicine, is already prevalent in today’s world, and price-based demand-side response measures risk worsening these challenges. While staying within the carbon budget is necessary, so too is ensuring that the most vulnerable members of our society do not suffer disproportionately in doing so. As we push for a complete overhaul of the electricity system to end its dependence on carbon-based fuels, we have an opportunity to push for the new system constructed in its place to reduce, rather than worsen, current energy injustices including energy poverty.

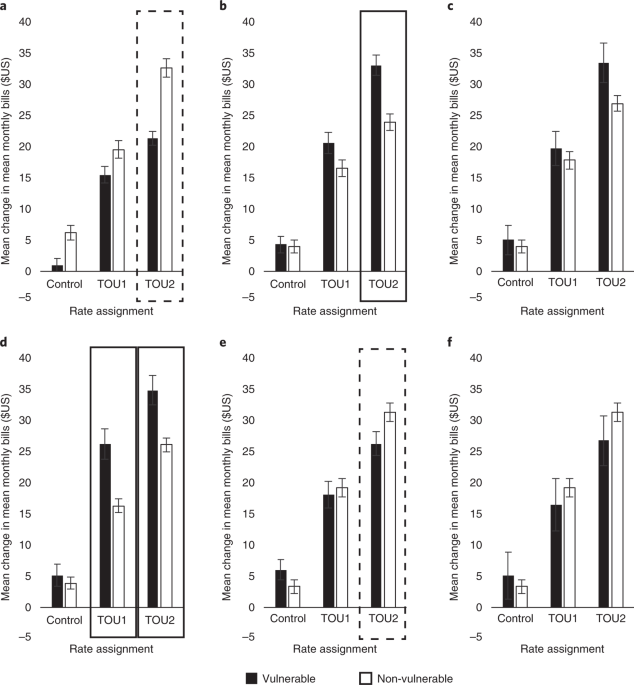

This is the motivation behind the current study, which examines static time-of-use rates, a relatively simple demand-side response mechanism. The time-of-use rates we examined charged more for electricity used during the evening, and the design of rates used in this southwestern utility pilot led to across the board bill increases in summer. The elderly and people with disabilities struggled to adjust to these higher evening rates and faced disproportionately high cost increases compared to their non-vulnerable counterparts. We also find indications that attempts to control electricity bills when placed on time-of-use rates may be detrimental to health, particularly for ethnic minorities and those with disabilities.

It is not surprising that these groups faced worse outcomes – the groups selected for our study were expected to face energy poverty due to systems that simply are not designed for them, as discussed in energy justice and energy poverty literature. However, our findings that the time-of-use rate considered in the study worsened hardships faced by these groups that are already struggling should be a call for an expansion of research in this area. Design of cost differentials and lengths of times when electricity costs more appears to be critical in predicting how badly vulnerable groups are affected, and which ones face greater hardship. With careful rate design, it is possible that some vulnerable groups may benefit from demand-side response measures compared to existing rate designs. In our study, low-income and ethnic minority households actually saw smaller bill increases than their non-vulnerable counterparts. There may thus be a possibility of designing demand-side response rates that reduce rather than increase existing injustices and energy poverty struggles, though the rate design we examined did not yet achieve this.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Energy

Publishing monthly, this journal is dedicated to exploring all aspects of this on-going discussion, from the generation and storage of energy, to its distribution and management, the needs and demands of the different actors, and the impacts that energy technologies and policies have on societies.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Microgrids and Distributed Energy Systems

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in