Tiny fossil titans of the seafloor

Published in Earth & Environment and Ecology & Evolution

Setting the scene

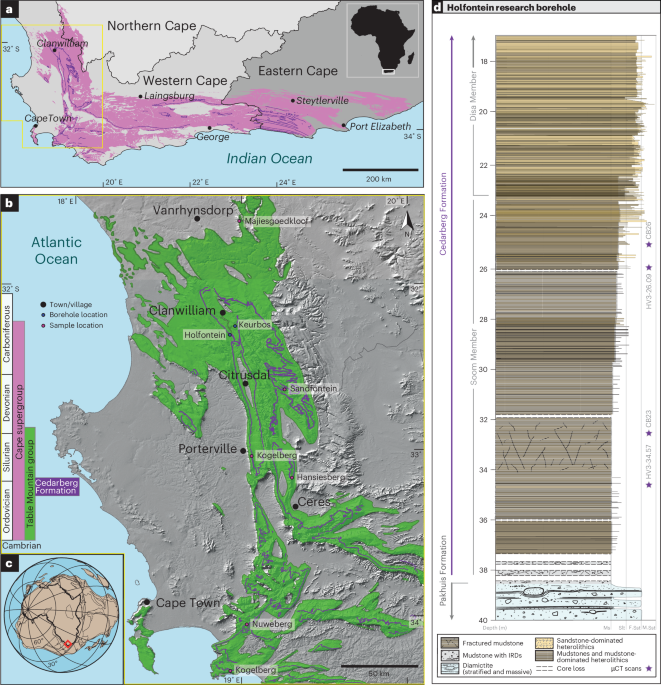

Some mountains just look ancient! This is true of the Cedarberg Mountains, a paradise for outdoor enthusiasts, about two hours’ drive north of Cape Town. The sculpted sandstone cliffs, jagged ridges, and windswept plateaus make one feel as if time runs differently here. Yet, inside these rocks is a story even older than the mountains themselves: the traces of tiny, resilient sea creatures that once helped to keep Earth’s oceans alive during one of the most difficult periods in our planet’s history.

To understand this, we must time-travel deep into Earth’s geological past, 444 million years ago, to a time when the Cedarberg rocks were forming layer-by-layer at the bottom of an ancient sea. Picture an icy, fragile world, slowly being released from the grip of a brutal ice age. An ice age so severe that it wiped out about 85% of life on Earth, far worse than the event that later doomed the dinosaurs!

Image credit: Simon Andrews

Unlikely heroes

Beneath the waves, in the shadowy depths of the seafloor, we meet the unlikely heroes of our story. The mud here was dark, suffocating, and almost entirely devoid of oxygen; a place so hostile that most creatures could not survive. Yet, in this bleak underworld, a tiny, resilient community manages to thrive. A community made up of minute nematode worms burrowing through the mud, and single-celled foraminifera feeding on the organic matter that drifted down from the waters above.

We know they existed, not because we find fossils of their bodies, but because they left behind thousands of tiny burrows and droppings in the mud that later hardened into mudrock layers in the Cederberg Mountains. Because nematode worms and foraminifera make the same kinds of burrows and droppings today, we can recognise their ancient traces preserved in the mudrock.

Amazingly, the same mudrock layers also preserve traces of their food: thin, carbon-rich bands of fossilised phytoplankton that once bloomed in the surface waters above and sank to the seafloor to become carpets of decaying marine snow.

Together, these two types of fossil give us a glimpse of an ancient ecosystem that was surprisingly impactful despite is modest size.

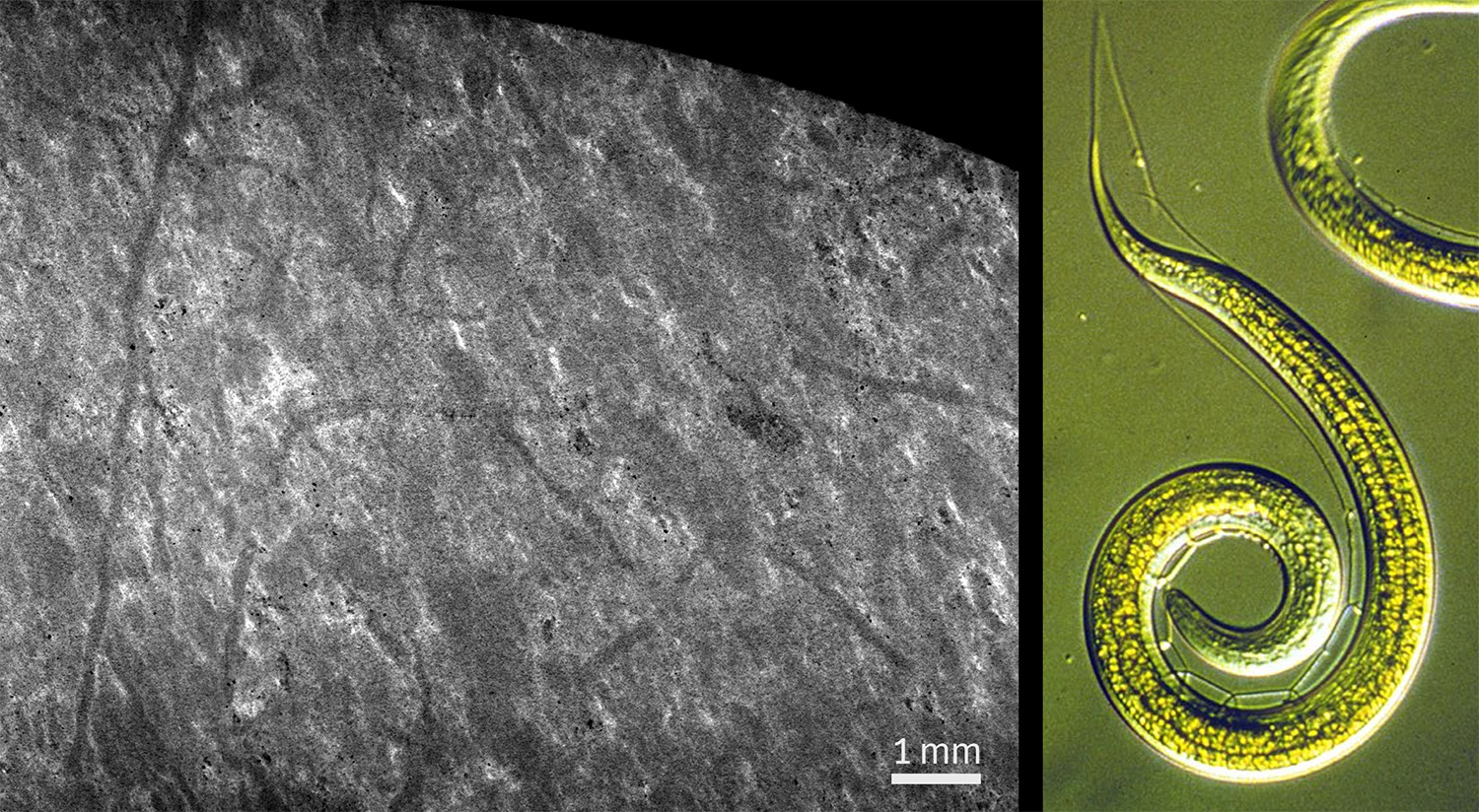

Minute horizontal fossil burrows criss-cross the mudrock layers. These burrows were made by ancient nematode worms, that probably looked very similar to the one in the picture on the right. (Right image: CSIRO Science Image, Left image: Claire Browning)

An unexpected discovery

The burrows that we discovered were not easy to find. Each one is only about the thickness of a human hair, and their colour and texture are almost identical to the surrounding mudrock. Under normal lighting, they vanish altogether; no amount of squinting will make them visible. That’s precisely why they went undetected for so long in the world-famous Soom Shale Lagerstätte.

We actually stumbled upon them by accident while searching for something entirely different.

Sometimes science is really boring and monotonous. On this particular day, I was frustrated by the black-and-white images I had been scrolling through for weeks.

These images, produced by CT-scanning the mudrocks, were supposed to reveal the shapes of ancient sand grains, helping us reconstruct how these rocks were once laid down on the seafloor. But they were giving me nothing! Just a soupy, featureless mass. That’s how research often goes; sometimes nature doesn’t give up its secrets easily.

But then, as I zoomed in, something caught my eye: delicate, almost imperceptible patterns crisscrossed through the mudrock layers. That’s when it struck me—I wasn’t just looking at grains of sand and mud. I was looking at the faint signatures of life, traces of a hidden ecosystem sealed inside the Cedarberg rocks for 444 million years.

Finding fossil worm burrows was incredible, but we had a hunch that there was an even bigger story hidden in the mudrocks.

Ancient behaviours that still power oceans today

Although any fossil this old and tiny is incredible in its own right, finding the burrows themselves wasn’t exactly groundbreaking; palaeontologists have been finding similar traces elsewhere for decades.

Still, we had a hunch that there was an even bigger story hidden in the mudrocks. If only we could get a clearer, three-dimensional picture. That’s when we decided to ask trace fossil experts Gabriela Mangano and Luis Buatois (University of Saskatchewan, Canada). They had grappled with similarly tricky traces in the past, and together with CT-scanning specialists Abderrazak El Albani and Arnaud Mazurier, were finally able to resolve the burrows in unprecedented detail.

Suddenly, the faint, hair-thin burrows were no longer just isolated markings. Observing thousands of them, we began to see changes in their concentration and orientation, revealing patterns linked to mudrock layers rich in fossilised phytoplankton. The patterns told a story: a dynamic system of seafloor life responding to pulses of food arriving from the surface waters above.

These tiny creatures weren’t just surviving; they were actively participating in a rhythm of nutrient and carbon cycling that mirrors processes still happening today off the coastlines of Chile, Peru and Japan.

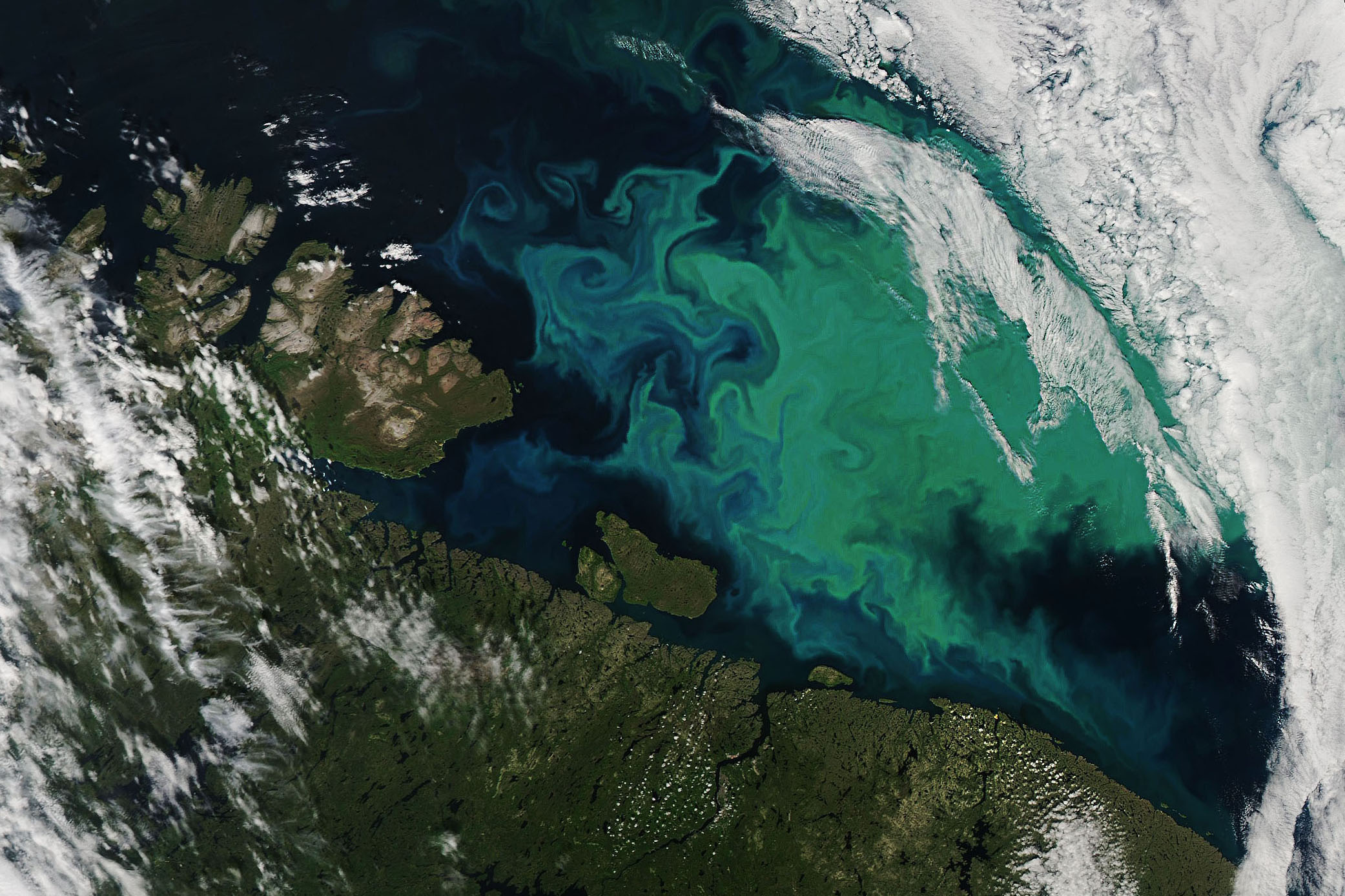

In these modern oceans, the surface waters periodically flush lime green with seasonal phytoplankton blooms. These blooms are made up of small, free-floating, sunlight-powered organisms that draw carbon from the atmosphere and convert it into organic matter. This is why they are often compared to rainforests, which also take up significant amounts of carbon and help regulate the planet’s climate.

But these blooms rise and fall quickly. When the phytoplankton die, billions of their bodies drift to the seafloor in massive pulses. Left to rot, they can strip oxygen from the bottom waters and release toxic chemicals, creating conditions where most animals cannot survive.

Most animals… but not all.

Worms and foraminifera thrive here. They are specialists in hardship, adapted to feast on this steady rain of dead phytoplankton and tolerate the low oxygen. And in doing so, they help to keep the system running: breaking down organic matter, recycling nutrients, and burying carbon in the sediment, where it can remain locked away for millennia. Locking away carbon like this helps to prevent carbon dioxide from building up in the atmosphere. This is one of the ways to prevents runaway greenhouse conditions.

Resilience written across deep time

The more we examined these trace fossils, the clearer it became: the tiny organisms that produced them were part of an enduring ecological engine, that had persisted for over 444 million years.

Set against the backdrop of one of Earth’s greatest mass extinctions, this community of tiny bottom feeders may have played an outsized role in the recovery of the oceans. While larger, more conspicuous creatures struggled to survive in the post-extinction world, the microscopic denizens of the muddy seafloor were keeping carbon and nutrients cycling, sustaining life from the bottom up.

Mountains are impermanent; worms are not

In an elegant extension of this story, the mud and sand that once settled on an ancient seafloor, and later hardened into the Cedarberg rocks, will eventually be eroded and carried back to the seafloor on South Africa’s west coast, starting the cycle anew.

Looking up at the imposing Cedarberg Mountains, it is difficult to grasp their impermanence, but in fact, mountains like these are far less enduring than worms. With their simple bodies, persistent behaviours, and ecological strategies, worms and other modest life forms have existed on Earth for millennia, outlasting mountains, glaciers, and mass extinctions.

Through it all, the intricate web of processes linking Earth and its inhabitants endures. Tiny or monumental, seen or unseen, resilience continues—holding the world together, just as it always has.

Blog written by Dr Claire Browning and Professor Sarah Gabbott, based on collaborative research with Professor Gabriela Mangano, Professor Luis Buatois, Professor Abderrazak El Albani, and Dr Arnaud Mazurier.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in