TOI-270: A Disneyland for exoplanet science

Published in Astronomy

By Maximilian N. Günther and Natalia Guerrero

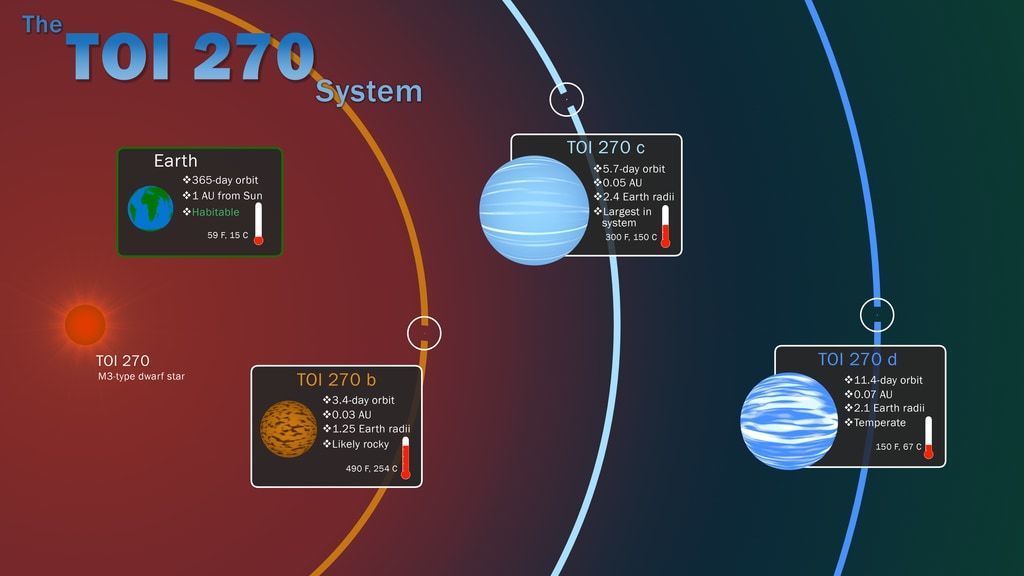

The star TOI-270, only 40% the size and mass of our Sun, has three planets in orbit: one slightly bigger than Earth and likely rocky, and two double the size of Earth and probably of a similar composition as Neptune - rocky cores covered by a thick gas atmosphere. Being one of the nearest and brightest such systems, TOI-270 is a true Disneyland for exoplanet science. It is relatively easy to observe and offers something for every research area, from formation and dynamics to atmosphere and habitability studies.

The story of TOI-270 started in our TESS Science Office at MIT. Twice a week our team comes together to vet and discuss the latest exoplanet candidates that our machine learning algorithms flag. If we agree a target has a high potential of being a real exoplanet, we post it publicly online as a “TESS Object of Interest”. This way, astronomers and citizen scientists worldwide can look at the data and follow the target up with their telescopes. This global team effort is organized as the TESS Follow-Up Working Group (TFOP). Whoever in the world gathers interesting data on the planet candidate uploads it to a shared platform, leading to collaborative results only possible by pooling individual resources. One of these TOIs alerted to the community was TOI-270. The system was extremely exciting, as a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation suggested the outermost planet might fall into a temperate zone around the star. While we later determined that the thick atmosphere on this planet makes life as we know it impossible, the more we dug into the data, the more interesting the system got for other reasons.

We are hopeful that TOI-270 will soon allow us to study the "missing link" between rocky Earth-like planets and gas-dominated mini-Neptunes. The Kepler mission found a "radius gap", meaning there are very few planets that are between 1.5 and 2 times the size of Earth. In the case of TOI-270, planets formed on either side of this gap in the same system, so we can trace back their formation history. For example, did the smallest planet once look like its large, gas-dominated siblings, and lose its atmosphere as it came too close to the star? This is referred to as the photo-evaporation theory, and could soon be tested on TOI-270. Hubble, James Webb, and the Extremely Large Telescope can make precise measurements of planets' atmospheres. The star’s steady nature will let any exoplanet atmosphere signals shine through, making the system an excellent laboratory to test these theories of planet formation and evolution.

The snapshot from the first observations of TOI-270 gave us the ability to dream up these bigger questions the system could answer. Astronomers and citizen scientists around the world pointed their telescopes at this thrilling system, gathering all the additional information needed to validate the system. The steps after that went very fast: we wrapped up all the measurements of planet size and temperature and analysis and asked our theorist colleagues to run dynamical models of the orbits of the three planets in the system. It was a giant team effort that in the end included 60 authors, not counting the hundreds of people behind the instrument’s design, engineering, and daily operation. The unique, open spirit of the TESS community made this discovery possible, and various follow-up efforts are already in progress. So stay tuned for more exciting TOI-270 news in the future. Go TESS!

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Astronomy

This journal welcomes research across astronomy, astrophysics and planetary science, with the aim of fostering closer interaction between the researchers in each of these areas.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in