Wastewater monitoring as a post-vaccine public health surveillance tool

Published in Earth & Environment, Genetics & Genomics, and Public Health

In the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic the University of Louisville Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute urgently brought together stakeholders from public health, the healthcare system and CEO’s of Louisville’s healthcare industry. Through initial meetings with the Mayor and with the Louisville Metro Department of Public Health and Wellness, we proposed the Co-Immunity Project with aims to assess and track the prevalence of COVID-19 in our county. With “seed” funding from local philanthropy including the James Graham Brown Foundation, the Owsley Brown II Family Foundation and the Welch Family we started the Co-Immunity project in May of 2020. We mailed tens of thousands of invitations to households chosen through stratified random sampling to be representative of the population. These residents were invited to mobile testing sites for nasal swab PCR testing and blood tests for seroprevalence. When we started the project, we did not initially know how long it would need to run. Ultimately, the Co-Immunity project obtained data for SARS-CoV-2 in Louisville-Jefferson County, Kentucky, from 7,296 adults by invitation and additional 7,919 who were not turned away when they sought testing at the sites as a public service. This continued for eight waves from June 2020 through August 2021. We also compared results with administratively reported rates of COVID-19.

At the time we started the Co-Immunity project, we knew that we wanted to not only enroll patients but also incorporate recently communicated findings of SARS-CoV-2 in municipal wastewater (Ahmed et al., 2020). We had been running for several years a community-based clinical study which included wastewater sampling (Kumar et al., 2022) in partnership with the Louisville-Jefferson County Metropolitan Sewer District and enhanced our collaboration to add wastewater surveillance to the Co-Immunity Project. A small field portable robot with a tube into the sewer pulled sewer water of several thousand to hundreds of thousands of residents every 15-minutes into our sample container over 24-hours, we then repeated this process at 17 sample sites twice a week. This wastewater work was ultimately supported by a contract from the CDC and its nascent National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) division (Smith et al., 2022). The summary of the prevalence findings was reported in Keith et al. (2023).

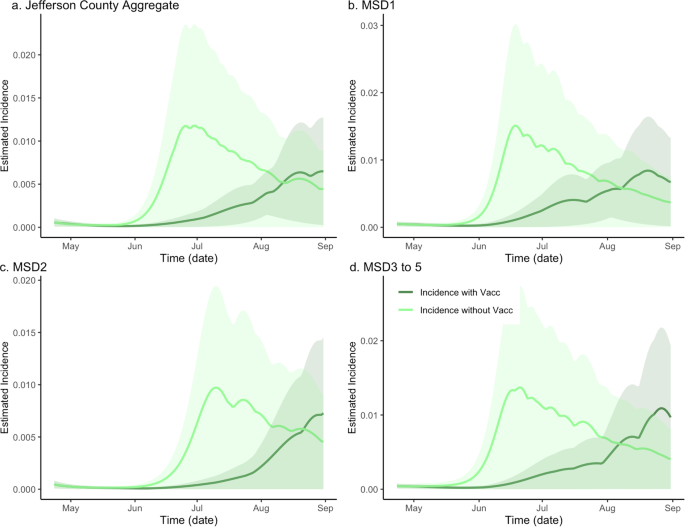

In our recent study (Holm et al., 2024), we explored whether wastewater data continued to be useful to estimate disease burden even after the COVID-19 vaccine rollout out in the United States. The model was built around three data sets: the amount of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, seroprevalence, and the number of cases admitted to hospitals between April 2021 through August 2021 in Louisville-Jefferson County. Using our model, we were able to estimate the 64% county vaccination rate translated into about a 61% decrease in SARS-CoV-2 incidence. We found that the hospitalization burden was closely reflected by the viral count found in the wastewater. Notably, we were looking to include the importance of continuing environmental surveillance post-vaccine, and our study provided a strong proof-of-concept.

More recently, the University of Louisville has transitioned from looking at the amount of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater to a custom panpathogen panel which measures 247 targets across common human respiratory viruses, viruses and bacterial resistance genes of interest. To date we have collected more than 3,000 wastewater samples for health monitoring. Wastewater monitoring as a public health surveillance tool has a potential for environmental epidemiological monitoring of infectious diseases for a wide range of local outbreak situations such as measles and also as a passive continuous mechanism for pandemic preparedness, where both future national and local policies could be informed.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Medicine

A selective open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary across all clinical, translational, and public health research fields.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Healthy Aging

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in