Watching Ruapehu Crater Lake: What does this tell us about an active volcano?

Published in Earth & Environment

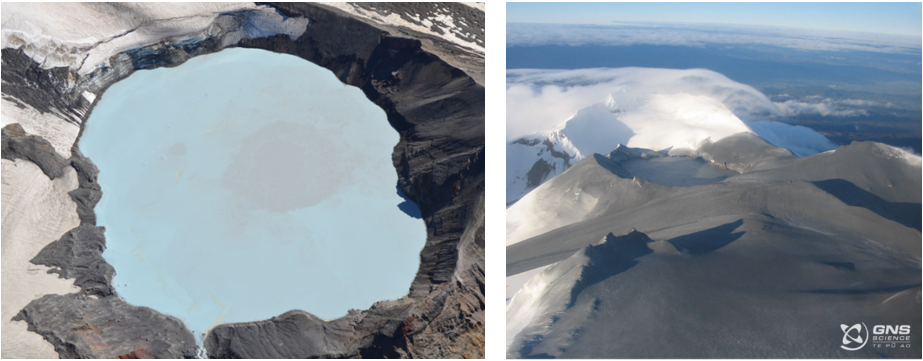

Ruapehu is a large stratovolcano located in the North Island of New Zealand, known mainly for the snow sports enjoyed on its mountain slopes during winter. Ruapehu has a large lake near the volcano's peak, known as Crater Lake, or to local tribes as Te Wai ā-moe. All historical eruptions at Ruapehu have occurred from volcanic vents found beneath the Crater Lake, with the most recent significant eruption in 2007 severely injuring a hiker camping near the lake. Ruapehu Crater Lake varies in temperature, colour, and steam conditions over time, which provide an insight into how the volcano works. Studying how the lake has visibly changed before past volcanic eruptions can also improve understanding of when and how Ruapehu may erupt in the future.

I began this study by looking at thousands of images of the Crater Lake that had previously been obtained by GNS Science, local iwi Ngāti Rangi, and various other sources. For every image I documented the lake colour, discolourations on the lake surface, and if steam was visible. Yes, this is as painful as it sounds. I looked at ways to automate this process, however due to differing camera angles and cloud conditions, and lack of consistent reference points, this proved difficult. Thankfully, some analysis had already been completed by GNS Science, so I built on this previous work. By chance, while I was on Ruapehu for a university field trip, my professor and I decided that I should climb to the Crater Lake and observe it. We found that the Crater Lake surface had numerous yellow and grey discolourations that changed location in a matter of minutes, something previously unknown to us. This was important as these discolourations were thought to indicate material being carried from the vents at the floor of the lake to the surface by volcanic processes, and could indicate where the volcano may erupt from in the future. We decided that systematic fieldwork with an array of cameras was necessary to better understand the location and timing of these volcanic processes.

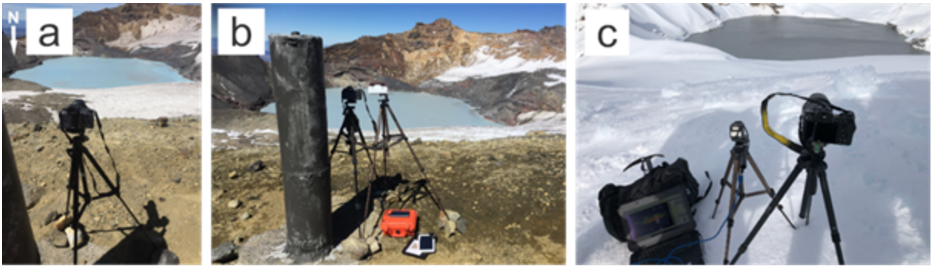

We recruited the help of scientists from GNS Science, the Department of Conservation, various universities, and local iwi, to help with data collection and analysis. Fieldwork involved carrying camera equipment, food, and hiking gear from the bottom of Whakapapa ski field to a vantage point overlooking Crater Lake, named Dome, a total of 20 times. This was a three hour walk with a heavy pack, including carrying a laptop to power an infrared camera, so I was always exhausted by the time I made it to Dome. I set up an array of ‘normal’ visible light, multispectral, and infrared cameras to capture images at 10 second intervals, left the cameras for a few hours, and then descended back down the mountain. I later collated the images together to create timelapse videos showing how the Crater Lake surface changed over time.

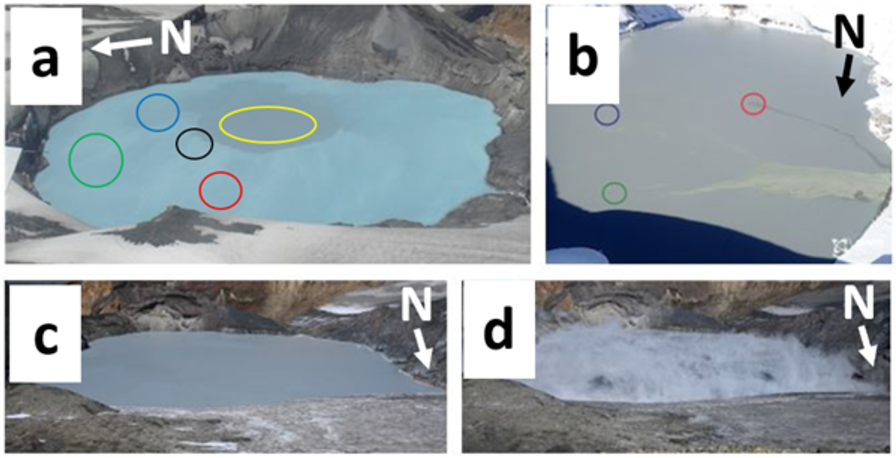

From the visible light images of the Crater Lake, we identified entire changes in lake colour from blue to grey, localised circular grey discolourations that we referred to as upwellings, localised elongate yellow discolourations identified as sulphur and referred to as sulphur slicks, and varying amounts of steam above the lake surface. The infrared imagery showed no useful information due to steam and the low angle view from Dome obscuring the lake temperature.

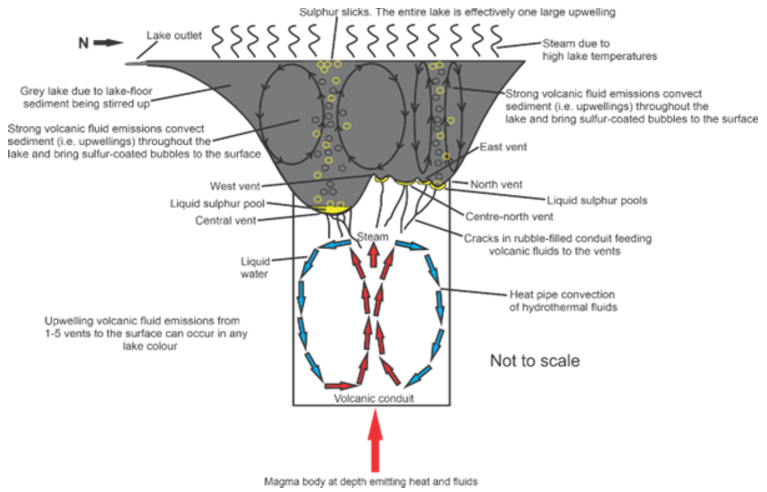

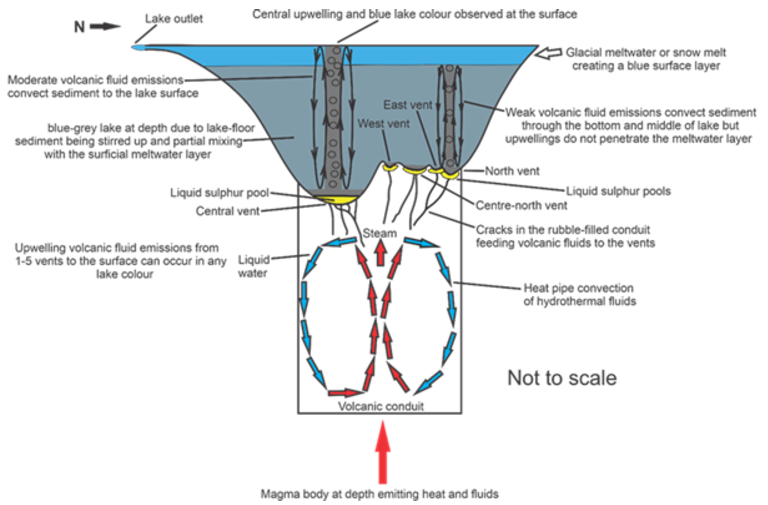

Circular grey upwellings are interpreted to be lake-floor sediment carried to the lake surface by volcanic fluids. These upwellings varied from metres to hundreds of metres in diameter, and either appeared and disappeared in less than 10 minutes, or remained present for hours. The locations of upwellings were used to identify five vent locations beneath the Crater Lake, three more than were previously known. Upwellings from the central vent were much larger than the other 4 upwelling locations, suggesting that a grey lake only resulted from central vent activity. Yellow or black elongate sulphur slicks are composites of thousands of small bubbles coated in sulphur, and are produced by volcanic fluids rising through a layer of liquid sulphur at the bottom of the lake and then being carried to the surface. Steam above the lake surface was only seen when the lake temperature was over 30 °C, with it being more abundant on cloudy days. The shape of the steam was circular during low wind conditions, and in high winds it formed sheets of steam blown across the lake.

We analysed the Crater Lake colour before historical volcanic eruptions at Ruapehu, finding that the lake colour was grey in the month before 97% of eruptions. This suggests that grey lakes may appear prior to eruptions in the future. Entire lake colour changes to grey are caused by volcanic fluids stirring sediment throughout the whole lake, as illustrated in Regime 1 below. Colour changes to blue are caused by ice or snow meltwater entering the lake and travelling across the surface, which was often observed in Summer and Autumn, and is shown in Regime 2 below. A blue-grey lake is the most commonly observed lake colour, and results from a balance between volcanic and meltwater processes. Based on the correlation between lake colour and past eruptions, we recommend that a visible light camera be deployed to monitor Ruapehu Crater Lake.

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Applied Volcanology

This is an international journal with a focus on applied research relating to volcanism and particularly its societal impacts. Characterising volcanic impacts and associated risk relies on not only quantifying physical threat but also understanding social and physical vulnerability and resilience.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Data Visualization and Effective Communication in Volcanology: Cross-disciplinary Lessons from Research and Practice

Journal of Applied Volcanology is calling for submissions to our Collection on Data Visualization and Effective Communication in Volcanology: Cross-disciplinary Lessons from Research and Practice.

This collection will highlight effective approaches for visualising and communicating volcanic information: from monitoring data to hazard model outputs, through to risk, impact, vulnerability information, and more.

Effective communication of technical information is critical to enhance the understanding of a volcano’s history, status, or forecast, and is vital for effective risk management. However, it is important not just to consider the aesthetic qualities of visual displays, we must consider how our visualisation and communication choices impact people’s responses to information, including how it may affect their decision performance. The effective display of critical information also impacts trust in the information, and the source of the information, particularly when uncertainty is present. Lessons for effective communication and visualisation can be drawn from numerous fields, including design science, UX, psychology, communication studies, informatics, GIS, data science, etc. Factors that can influence interpretation and use of visualisations include aspects such as volume, colour, graphics, symbology, uncertainty, and integration of local and cultural knowledge. Additionally, with the growth of big data, both AI and deep learning present opportunities and risks in the visualisation and use of complex volcanic information.

In this special collection, we welcome submissions on a range of topics exploring effective information visualisation, considering the full spectrum of approaches to displaying complex science: ranging from effective maps and displays of spatial and three- or four-dimensional information, through to the use of symbology and information products for non-technical users, and beyond. We are interested in papers presenting research studies, case studies, and literature reviews, including evidence for best practice, techniques to identify and evaluate user needs and preferences, evaluation methods, software for visualisation and management of big data, and other topics that support effective communication.

Prior abstract submissions are not necessary, however the Guest Editors welcome authors to discuss ideas they may have for manuscripts prior to submission. Springer Nature offers several options for open access fee support, these include institutional open access agreements, reduced fees via waivers for corresponding authors based in lower income countries (as defined by the World Bank), and case-by-case waivers or discounts based on financial need. The Journal of Applied Volcanology also has a limited number of partial and full fee waivers that can be assessed on a case-by-case basis based on need. If you are interested in applying, please indicate your interest at the point of manuscript submission and outline your case in your submission letter. More information can be found here.

We also invite applications to join the guest editor team for this special collection. If interested, please contact the Editor-in-Chief, Emma Hudson-Doyle.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 11: Sustainable Cities & Communities and SDG 13: Climate Action.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Ongoing

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in