What a billion words on China's Twitter reveal

Published in Social Sciences, Computational Sciences, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

What do our words say about our psychology? With researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, I had access to a giant database of over a billion words from 800,000 users on Weibo (China’s Twitter). We used those billion words in a study mapping regional differences across China.

Like Twitter, Weibo posts are short--often a sentence or two.

One thing we can do with all that data is get a fine-grained map of differences across China. We geo-located users to provinces and even prefectures (which are smaller, similar to US counties).

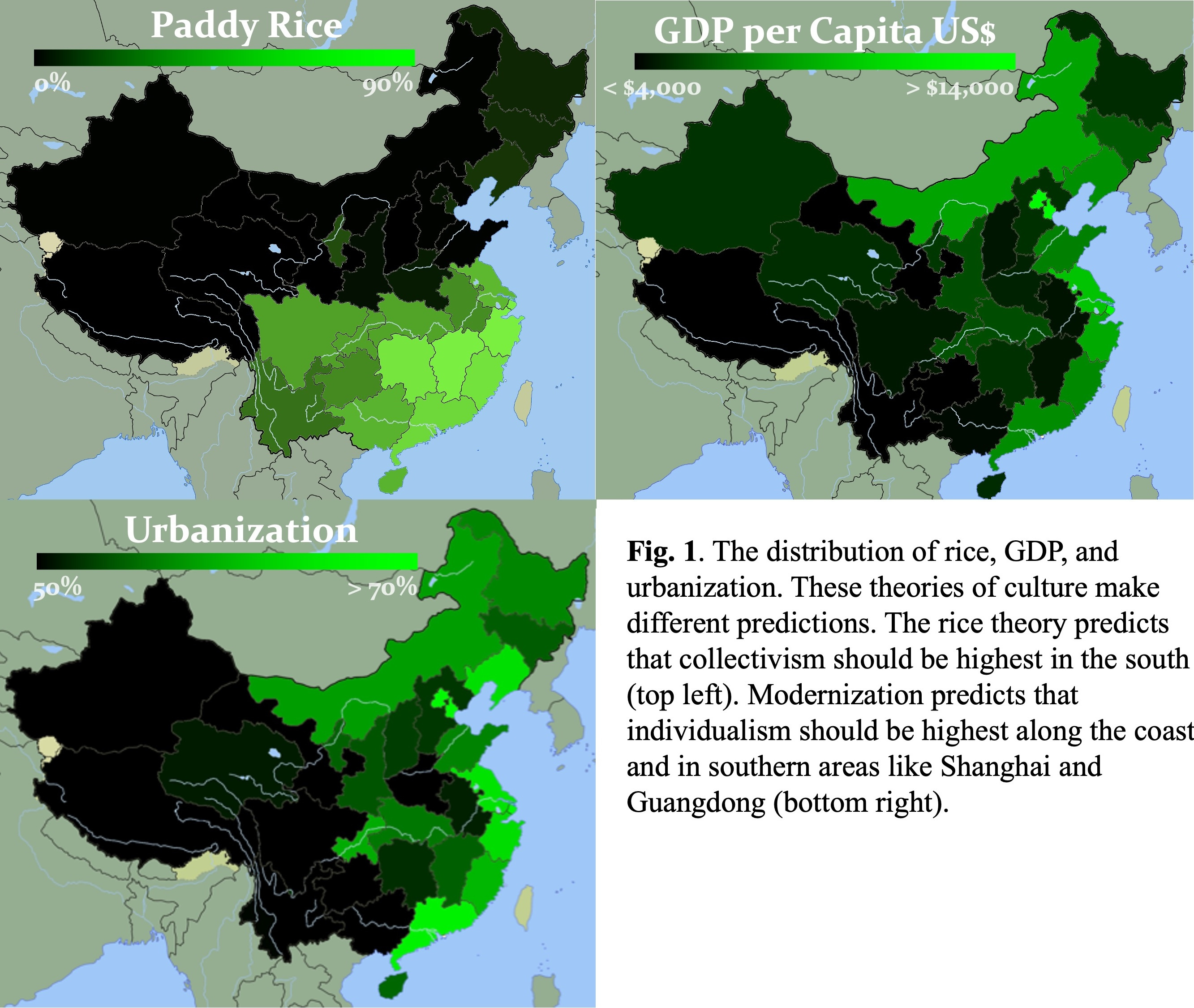

This fine-grained data can help us tease apart three theories about differences in China—two obvious and one less obvious. The first obvious one is urban-rural differences. I call this "obvious" because people talk a lot of about how huge urban-rural differences are in China. As just one example, this book calls them “two societies.”

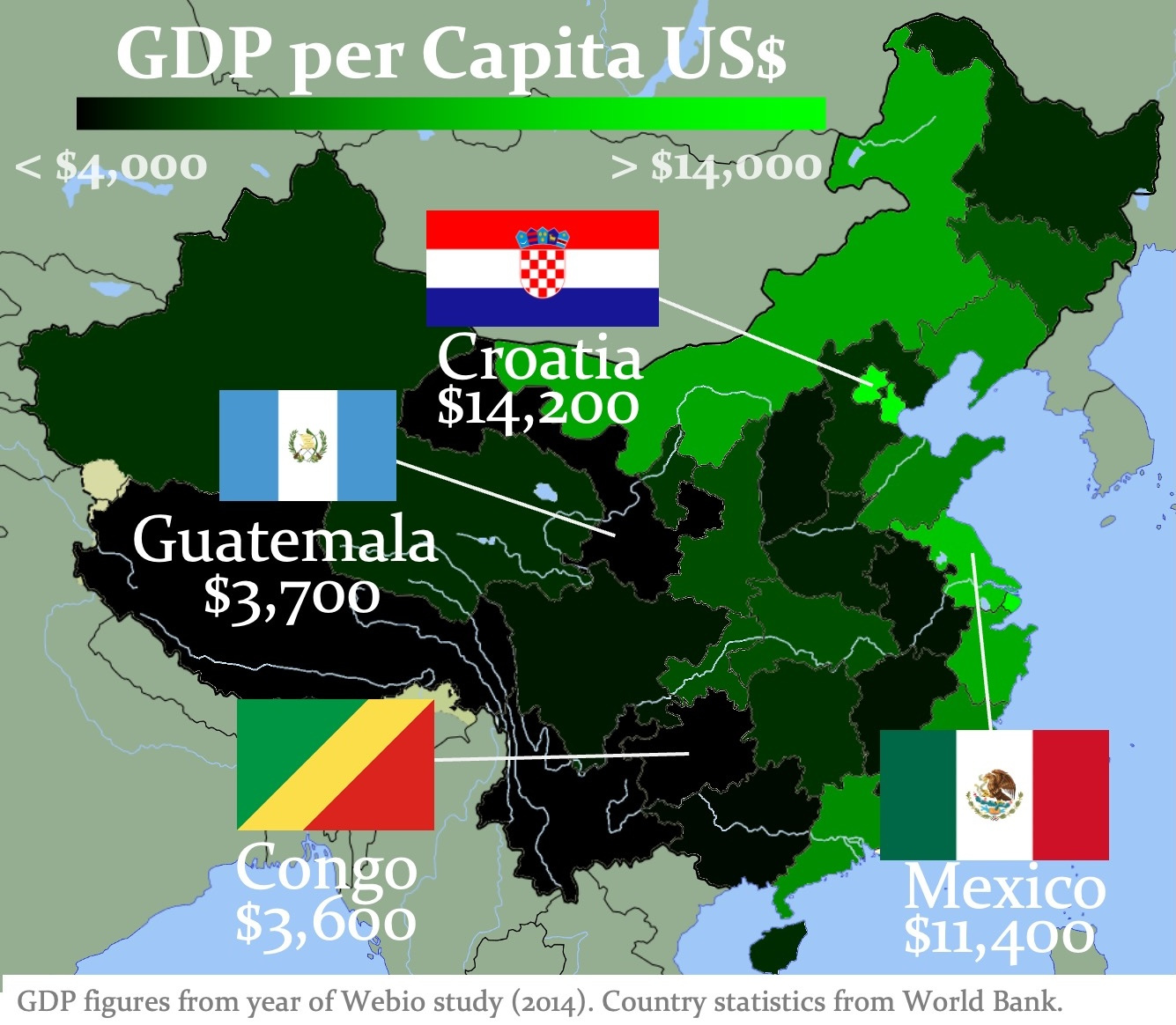

Another closely related idea is economic development. China developed rapidly in the last 25 years, but the economy still varies widely. In the year we collected our Weibo data, some provinces had GDP per capita on par with Congo, and others were on par with countries in Europe, like Croatia.

How would economic development change cultures? One very logical prediction people make is that more modernization is making China more individualistic.

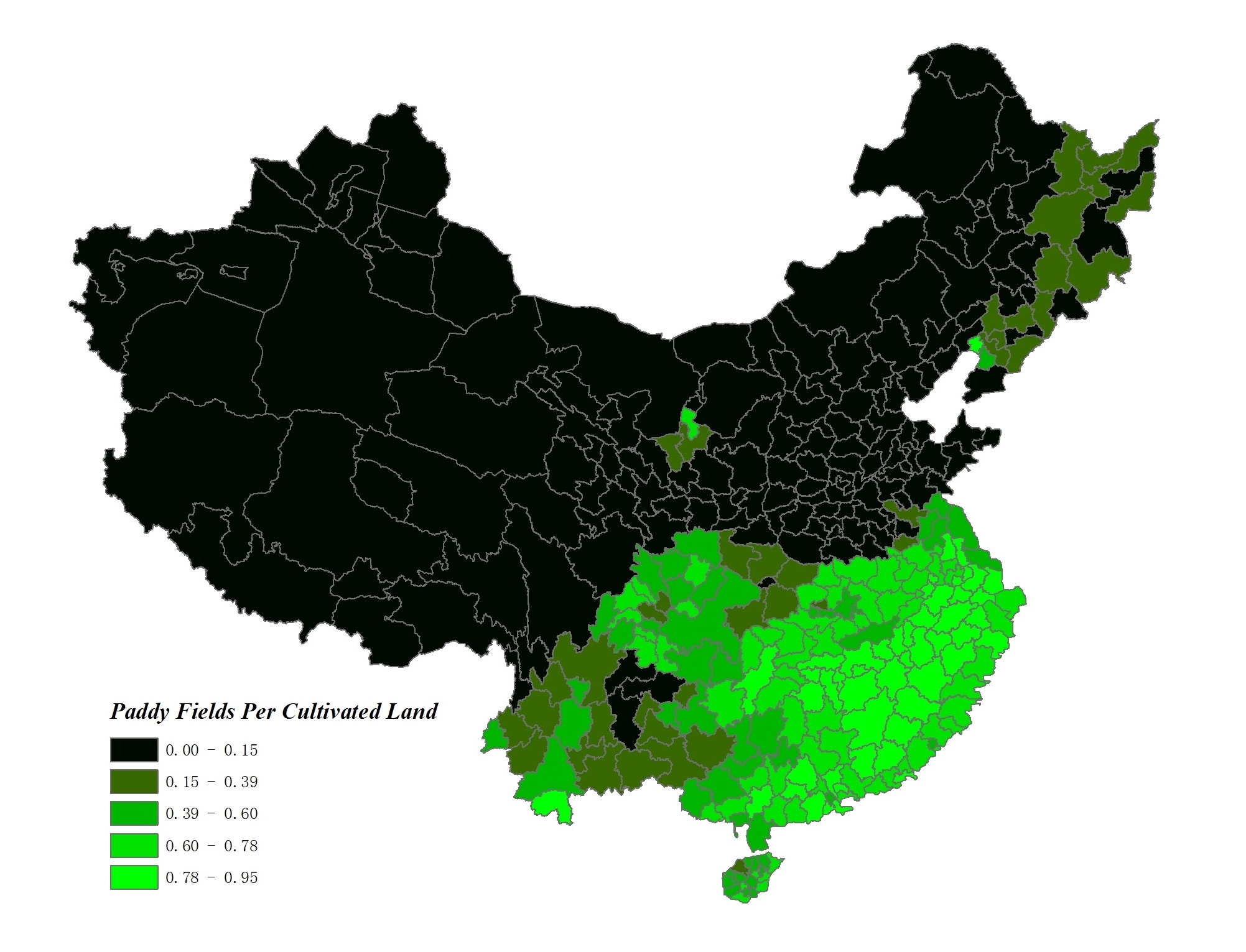

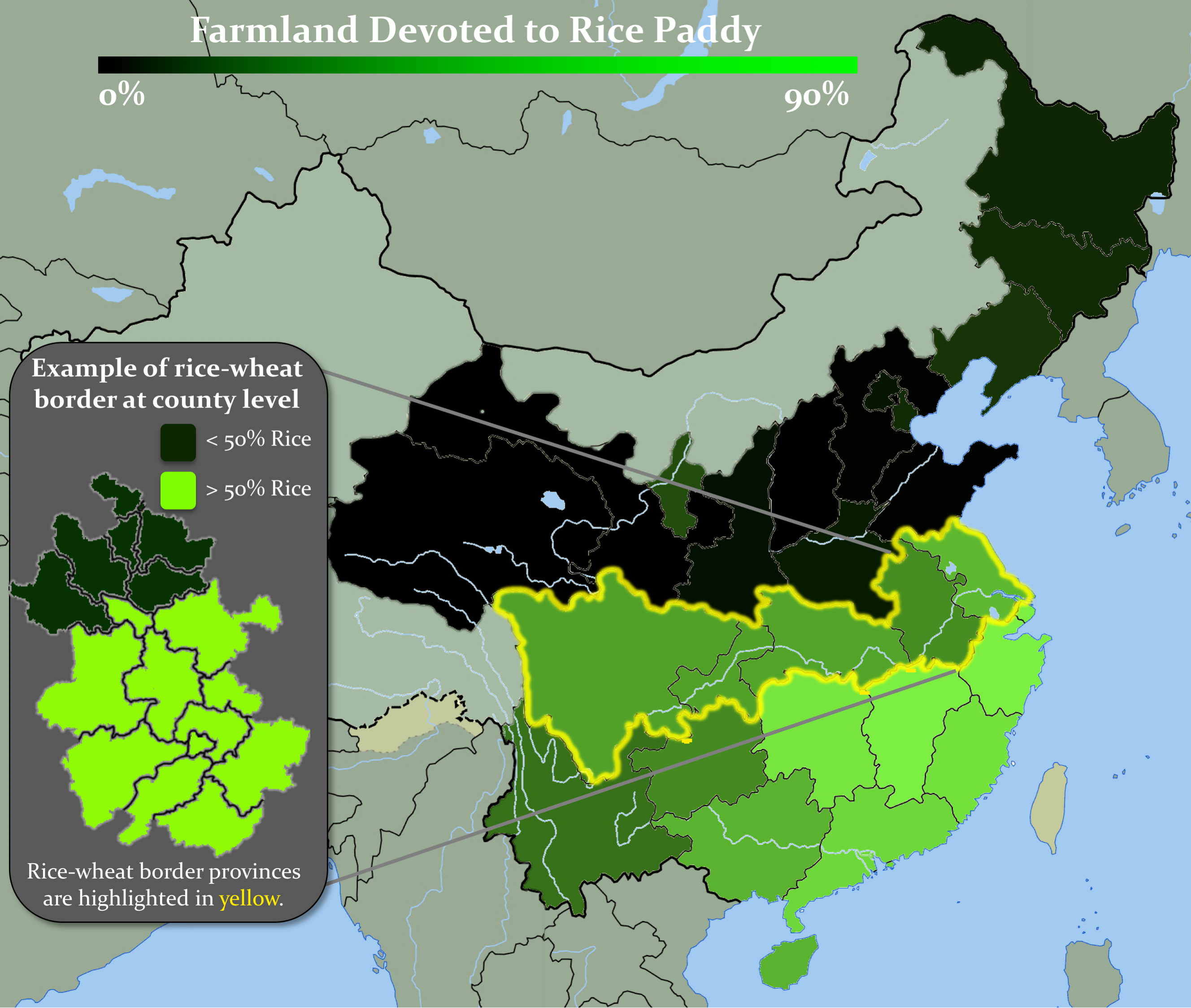

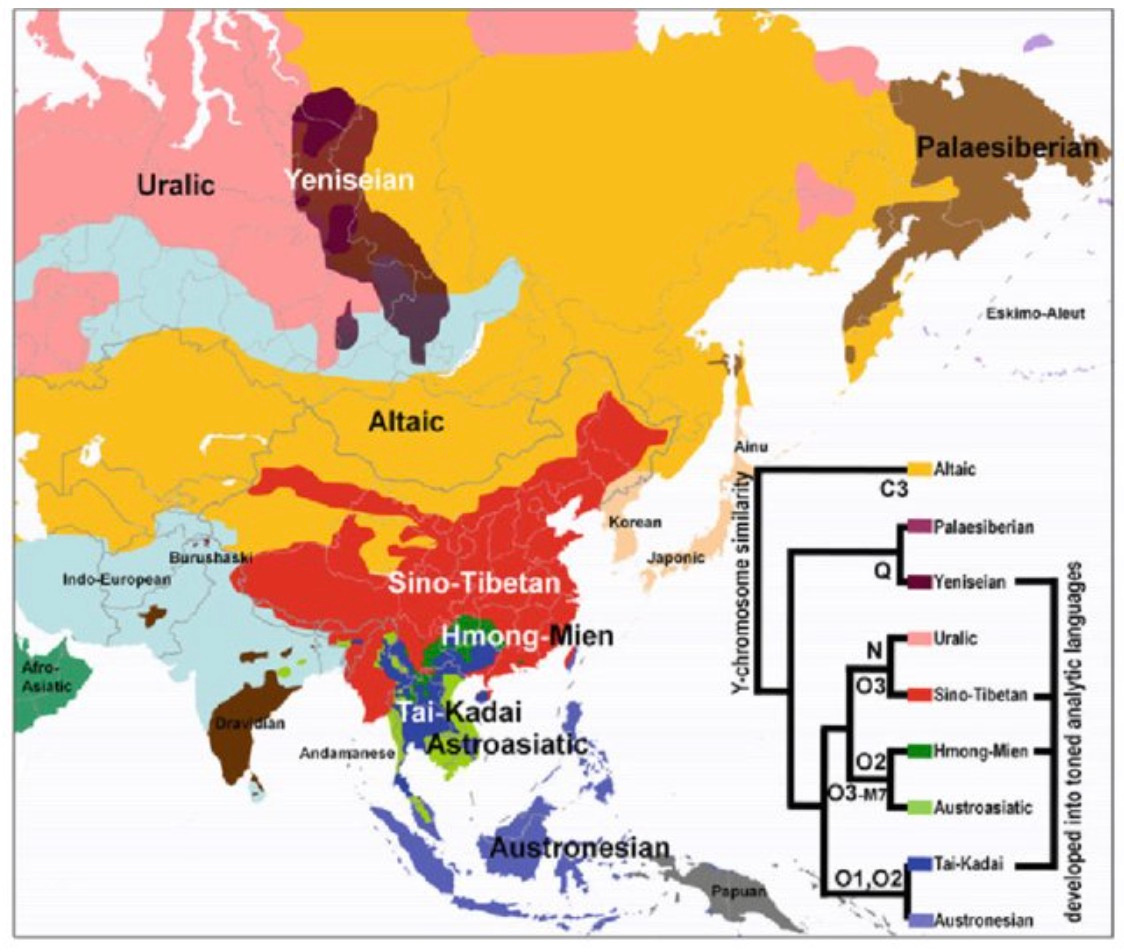

Here’s the less obvious theory: rice farming. Paddy rice was built on shared irrigation networks and required more labor than crops like wheat and corn. This theory can explain why studies have found that people in rice-farming areas tend to be more collectivistic than people wheat-farming areas.

Here’s a crucial point: rice and modernization make different predictions. Rice is concentrated in the south. But the south is also wealthier on average (so is the coast). This creates a showdown between competing hypotheses.

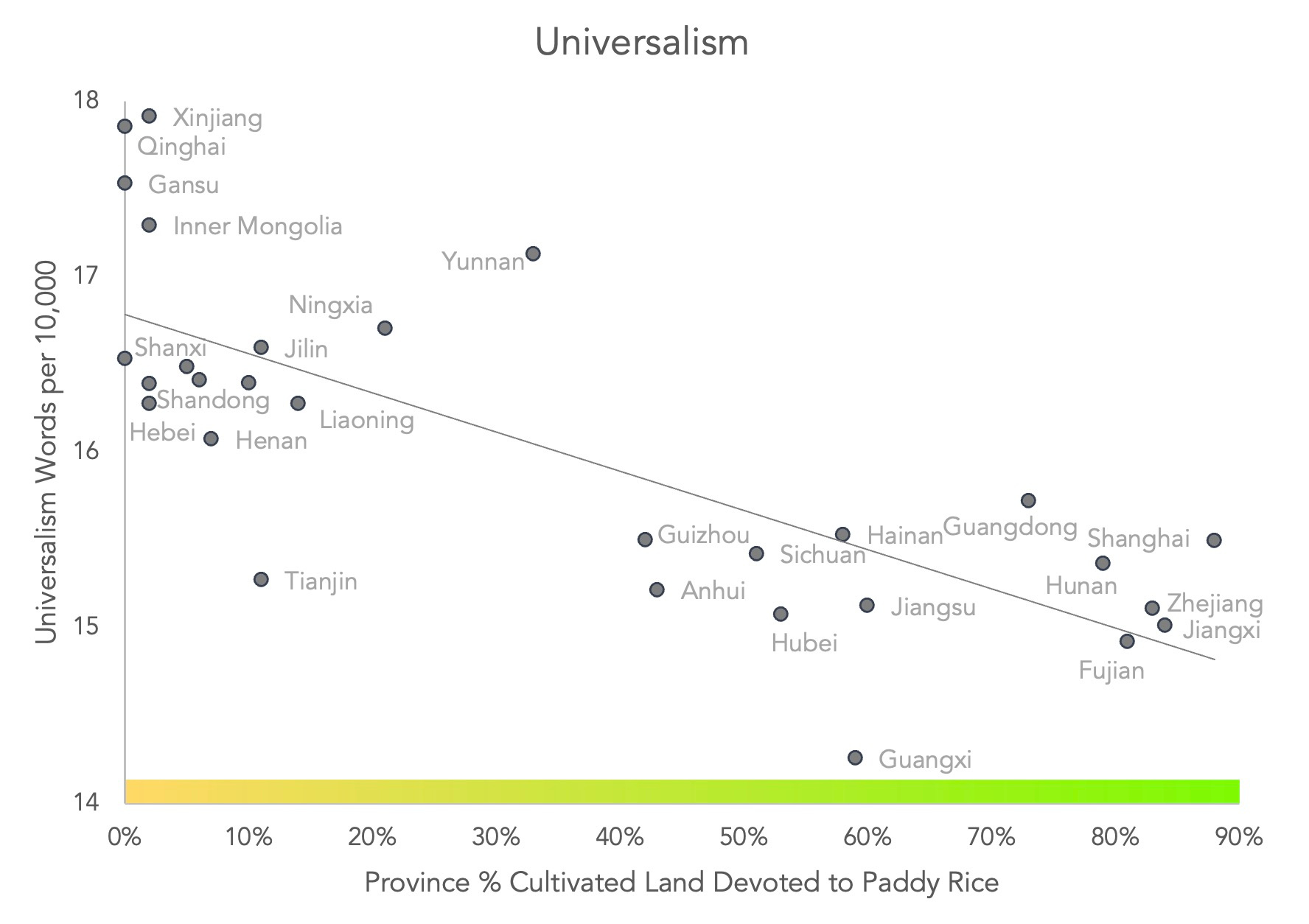

How do we measure culture in people’s words? One way we tried was to look at universalism words. It may sound paradoxical, but people in individualistic cultures emphasize broad, general social relationships (like “humanity” and “the people”). In contrast, people in collectivistic cultures emphasize close, specific relationships.

People in rice areas used fewer universalism words. GDP and urbanization were not significantly related to the frequency of universalistic words.

Another category we looked at was “assent.” People in rice areas used more words like “that’s right” and “yeah.”

The use of these assent words could be a sign of conflict avoidance. I felt like I experienced that conflict avoidance when I lived in southern China, which makes sense with rice farming's pressure to coordinate labor and water use with neighbors and extended family.

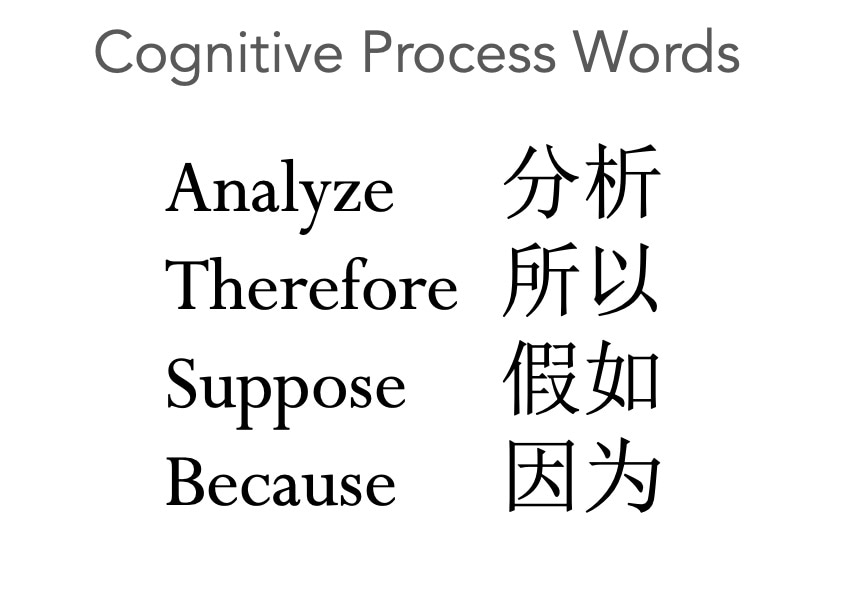

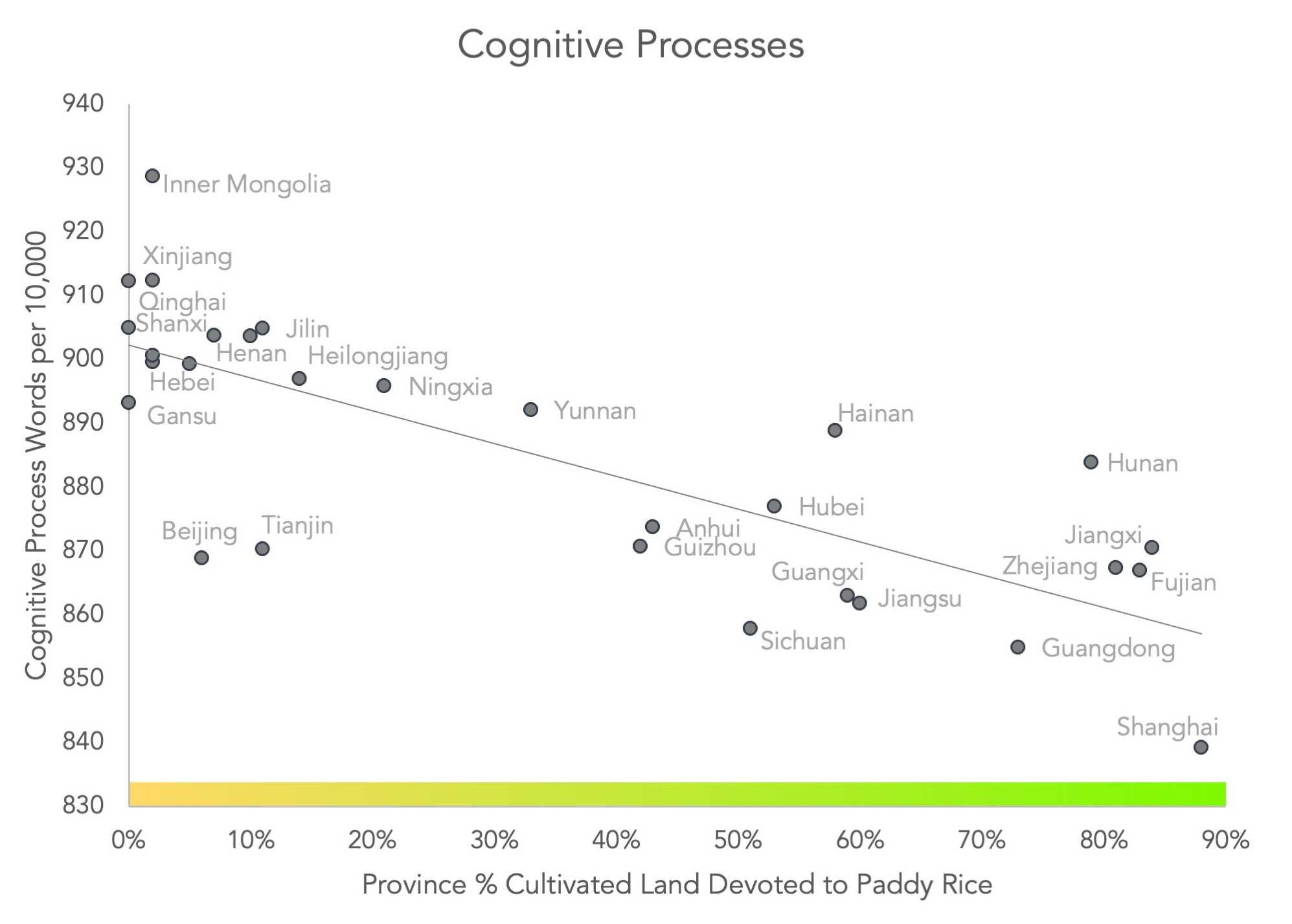

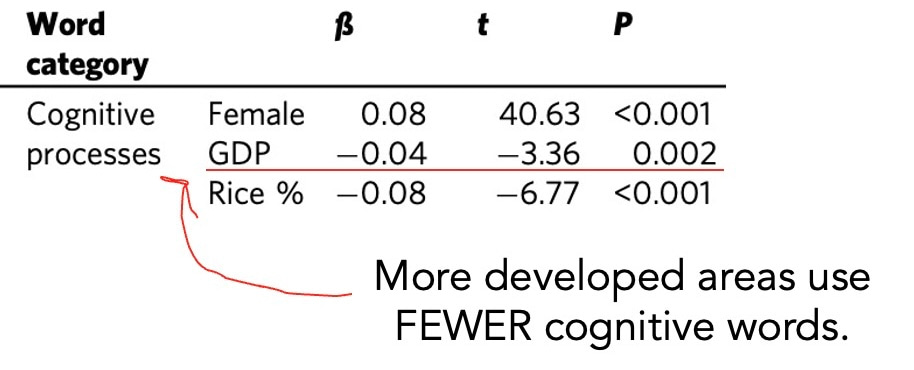

Next, we looked at "cognitive process" words, like “suppose” (假如), “therefore” (所以), and “analyze” (分析). We looked at these words because many previous studies have found that people in individualistic cultures tend to think more analytically. Analytic thought focuses on individual objects separated from the context, individual properties of those objects, and rules of abstract logic like non-contradiction. In contrast, people in collectivistic cultures tend to think more holistically, paying more attention to the context, emphasizing the relationships between objects, and prioritizing pragmatics and believability rather than rules of abstract logic.

Rice areas used fewer cognitive words, which fits with previous findings of more holistic thought in rice-farming areas. They also used fewer words about causation, like "due to" (由于) and "cause-effect" (因果).

I was surprised to see the results for modernization. It's logical to think that economic development would increase analytic thought because of increasing education (and if modernization is boosting individualism). However, economic development actually predicted less cognitive word use.

Although it's counter-intuitive, this result could fit with previous findings. Several studies have found that wealthier people tend to think more analytically. Yet my colleagues and I found that this link between social class and analytic thought does not hold in China (at least not in rice areas).

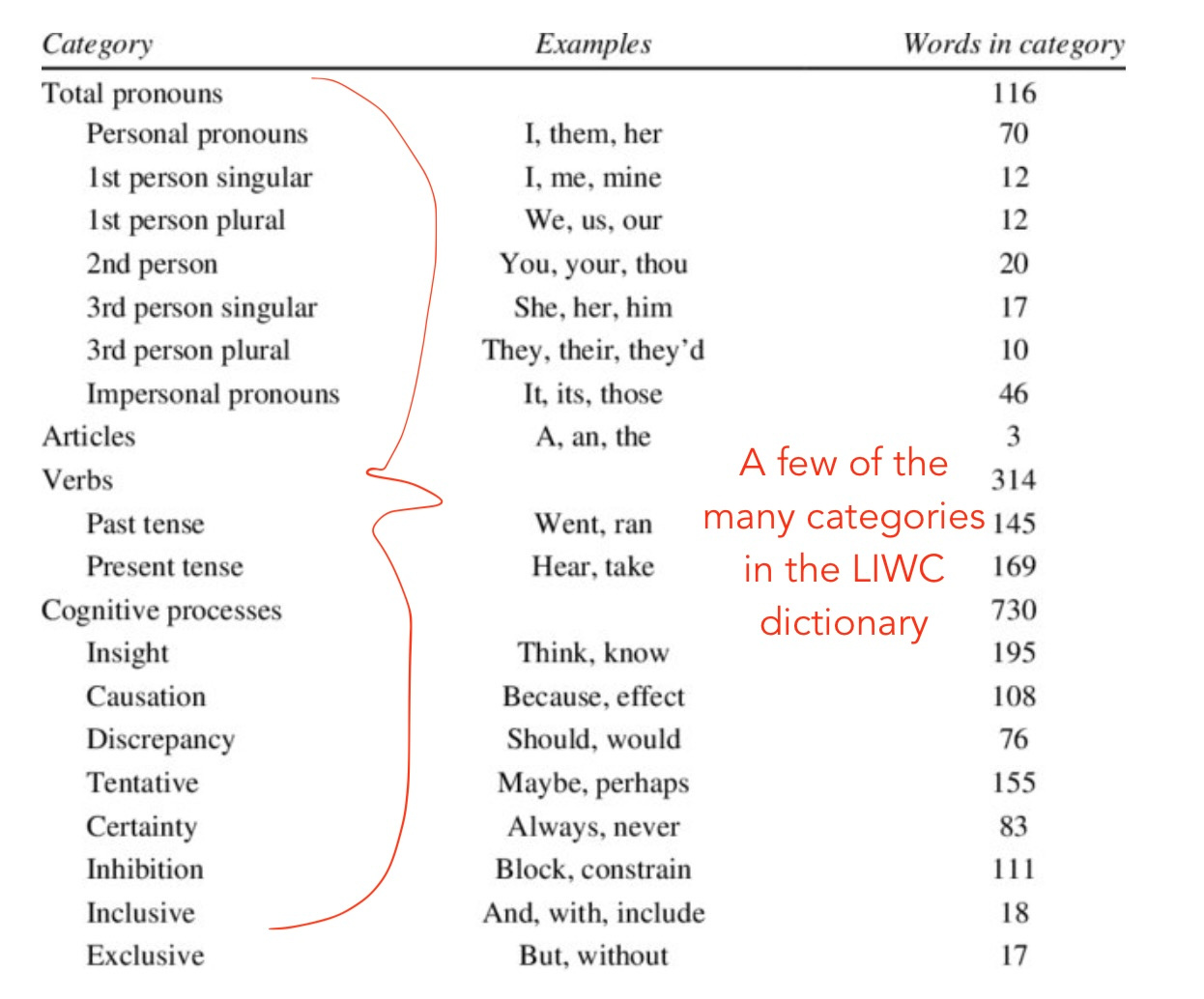

Up to this point, we were looking at “top-down” word categories. These are categories based on theory and from the established word categories of a popular database called “LIWC” (pronounced like “Luke”).

We also tried a bottom-up approach. In the bottom-up approach, we didn’t start with pre-conceived notions in our heads. Instead, we asked machine learning to analyze the words and tell us what types of words people tend to use together.

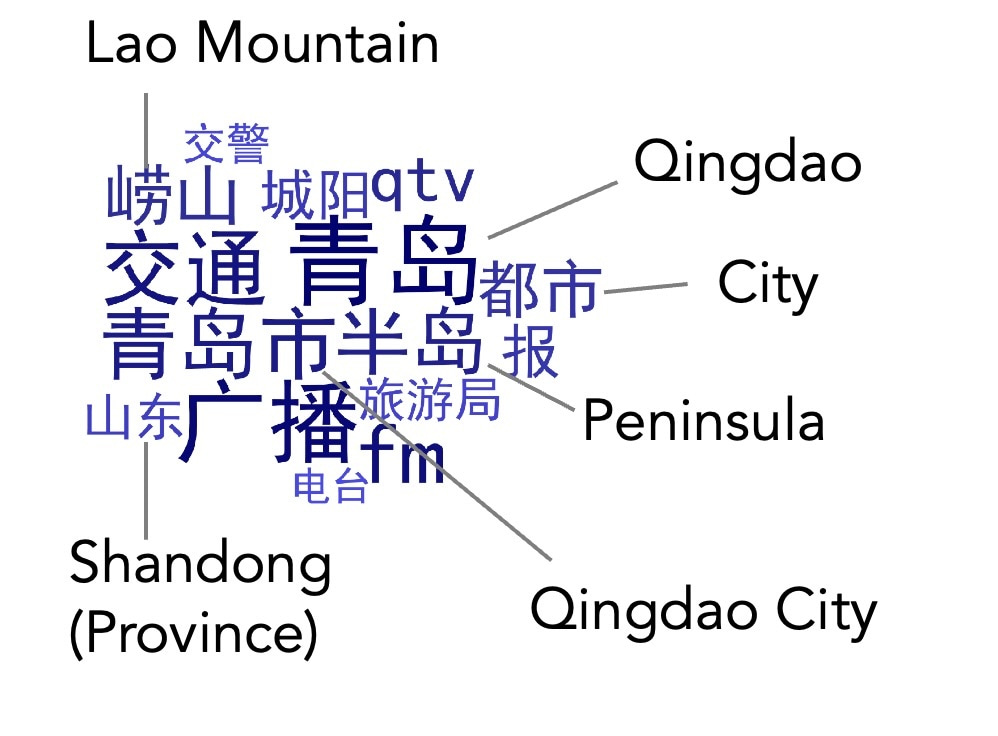

Some of the categories the machine learning found were boring. For example, people tended to use place names together, like around the city Qingdao (same as the beer Tsingtao).

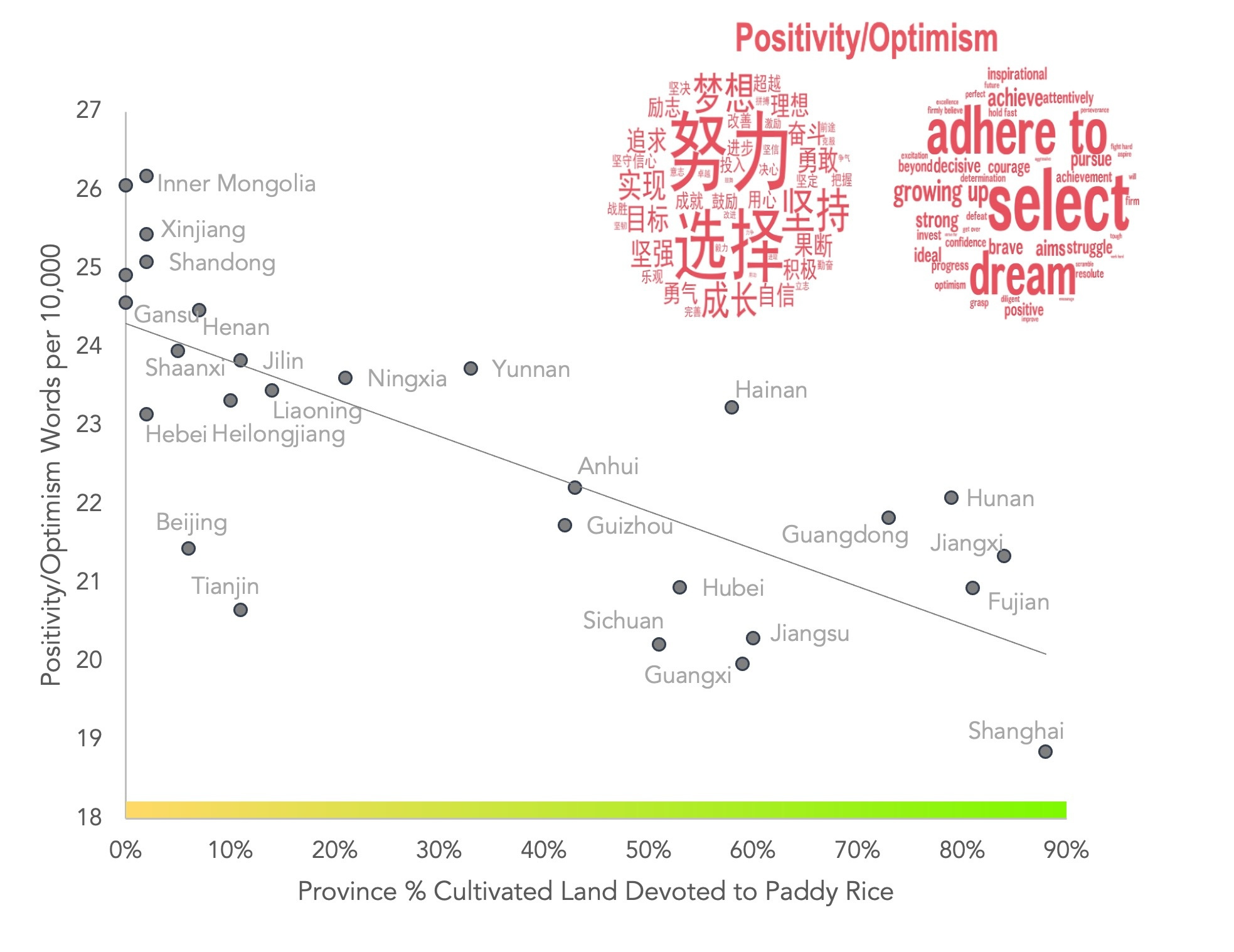

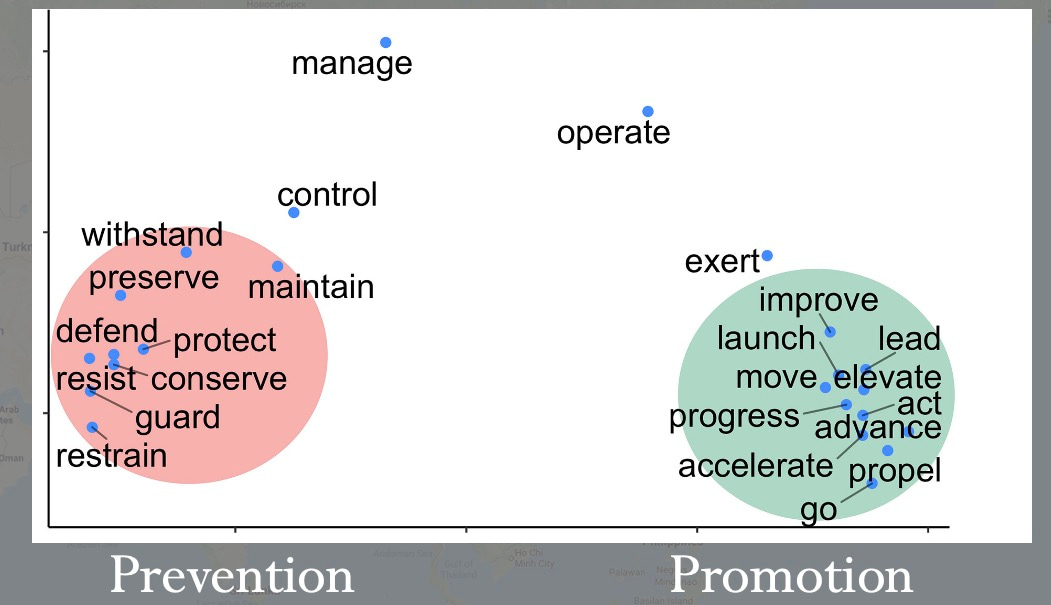

But others were psychologically interesting. For example, people in wheat areas tended to use words in a category of words like “dream,” “ideal,” “pursue,” and “decisive.” We called this grouping “positivity/optimism.”

This raises the intriguing possibility that wheat areas are more promotion oriented. People in a promotion-oriented mindset focus on gains and acquisitions, while often ignoring risk. Our results suggest people in rice areas are more prevention oriented—cautious, focused on preventing losses and avoiding failure.

Differences from China's Rice-Wheat Border

One difficulty with studying cultural differences is determining causality. It's one thing to establish that northern and southern China are different, but how do we know these differences come from rice and wheat?

One simple method is to measure other potential causes like economic development, education, and urbanization and put those in the model too. Of course, we do that in the study.

However, there are limits to that method. For one, it requires us to know what the potential confounds are and measure them precisely. But our measurements are imprecise. And there might be lots of other potential confounds we are overlooking, like experiences of political movements, historical events, and ecological differences like temperature.

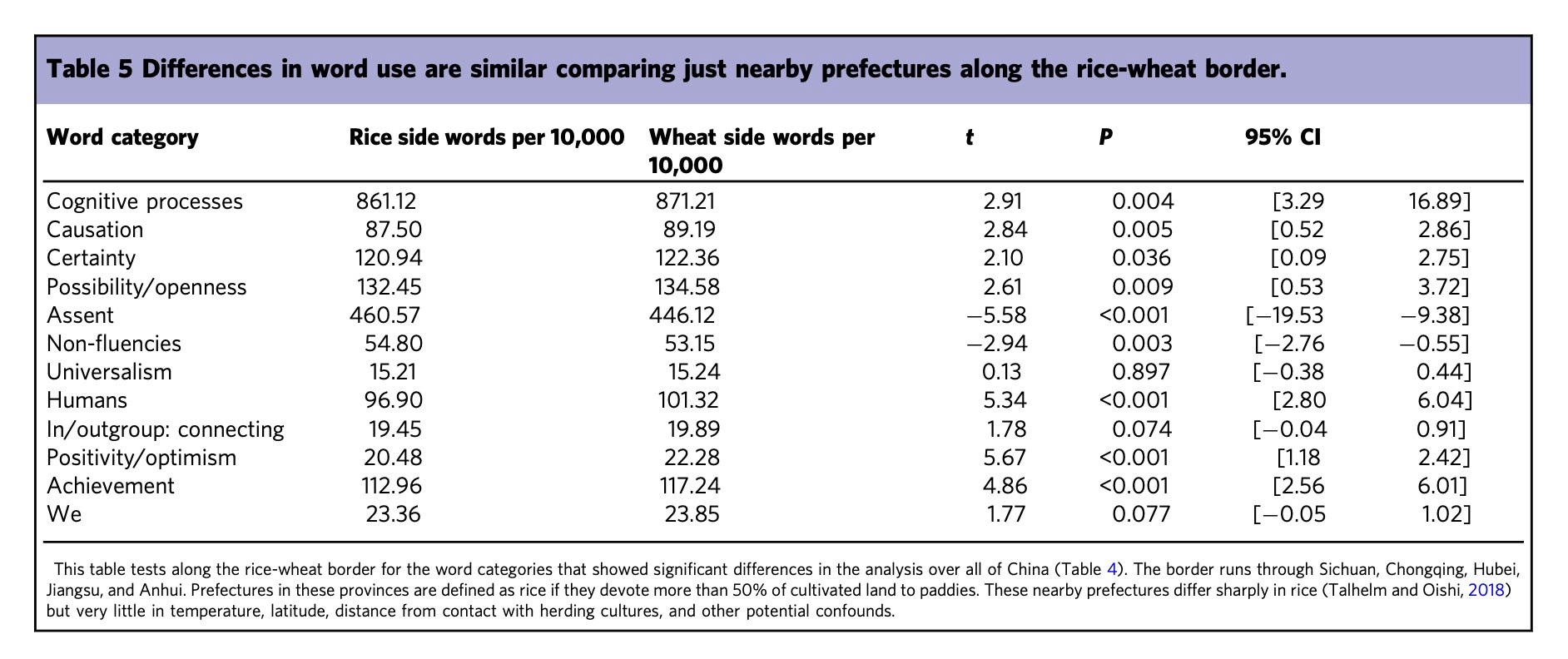

One way to get around those problems is to look at the rice-wheat border. Prefectures along the rice-wheat border differ a lot in rice and wheat but little on potential confounds like temperature and historical events.

So we re-ran the analyses just with prefectures along the rice-wheat border. Despite the smaller sample size, most of the rice-wheat differences held.

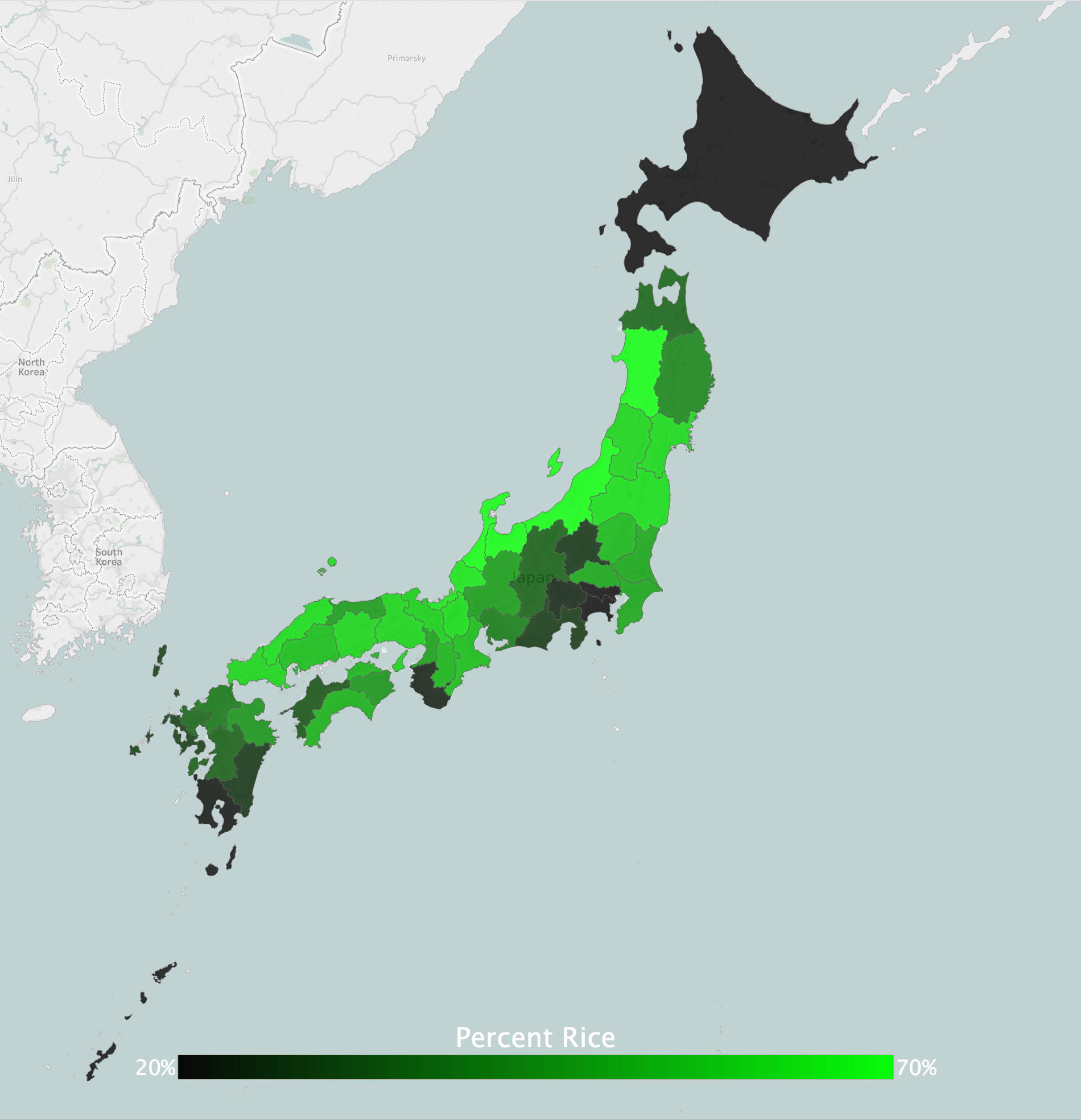

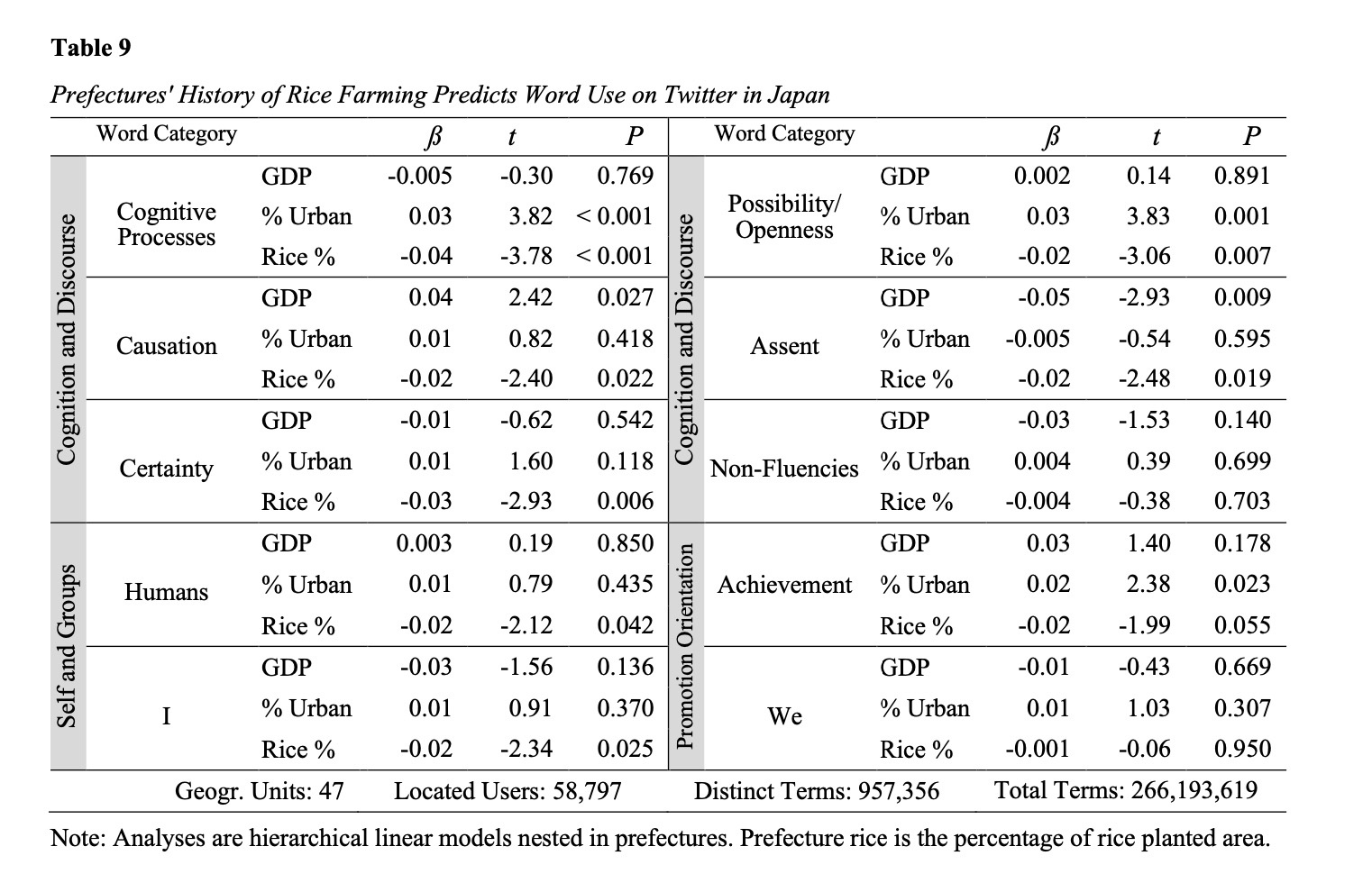

Japan as a Test Case for the Rice Theory

Finally, we tested our results in Japan. Most farming in Japan is rice, but there is some variation across regions.

Japan also uses a different platform (Twitter), and Japanese comes from an entirely different language family from Chinese. That lets us test whether the findings from China hold in a different context.

Several of the patterns held. Rice areas used fewer cognitive words and words about broad human relationships. But Japan did not show the same finding about agreement words as China.

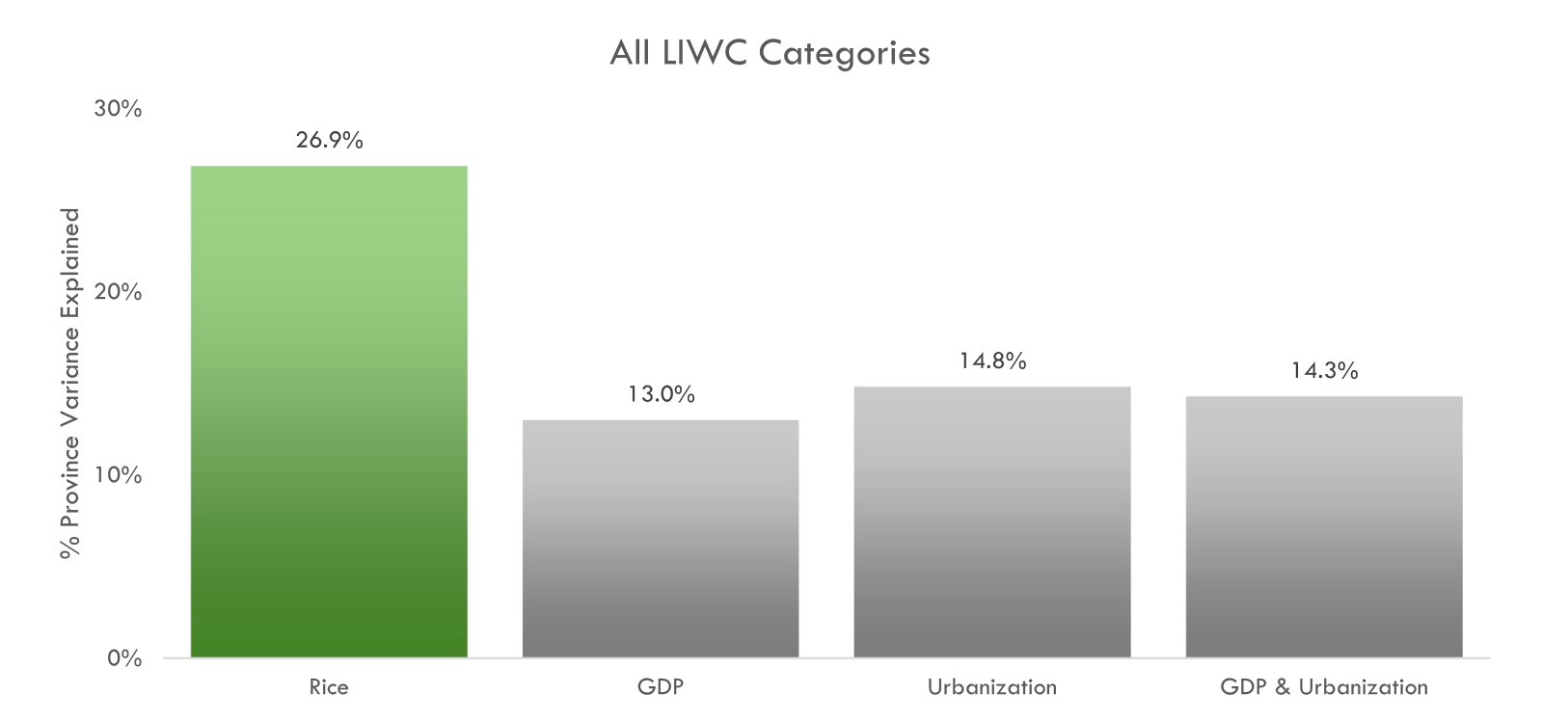

Horse Racing Rice and Modernization

So far, regions' history of rice farming seemed to be a better explanation of differences in China than modernization. But those results are only for a few word categories. We can test this more broadly in a "horse race" analysis.

To do that, we ran an analysis for each of the LIWC word categories and added up how much variation each theory can explain. Why use all of the categories? It removes any potential for me to cherry-pick word categories that I thought all along would work with rice. Even with this unguided approach, rice predicted about twice the variance across provinces as GDP or urbanization.

These results from a billion words on Weibo give us a window into cultural differences in China (and where those differences come from). Modernization is easy to see in China. It's in China's new office buildings, high-speed trains, and mega cities.

But the key to understanding China's cultural differences was in its past. The words people use in modern China were more connected to the less-observable history of rice farming than its present.

Follow the Topic

-

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications

A fully open-access, online journal publishing peer-reviewed research from across—and between—all areas of the humanities, behavioral and social sciences.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Interdisciplinarity in theory and practice

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Addressing the impacts and risks of environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices towards sustainable development

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 27, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Thanks to my hard-working co-authors, many working on NLP at U Penn: Sharath Guntuku, Garrick Sherman, Angel Fan, Salvatore Giorgi, Liuqing Wei, and Lyle H. Ungar. The paper is also available on SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5070871