What does it mean to belong? For students, it’s bound up in their gender and social class experiences

Published in Social Sciences

Feeling Like We Belong is Vital

To say that connecting with others and being part of groups and communities are fundamental aspects of people’s experiences is not a novel idea. For centuries, individuals from different disciplines, from writers to economists to epidemiologists have highlighted the importance of feeling part of a group. Overall, there seems to be consensus that belonging is a fundamental human need. Research has shown that a higher sense of belonging is associated with multiple positive outcomes, such as well-being, mental health, academic motivation, educational attainment and academic success. Therefore, there is tremendous interest among researchers to understand and promote a sense of belonging, especially for members of underrepresented groups, such as women in STEM, marginalized racial group member and individuals from low-income backgrounds. Indeed, a quick search on Google Scholar yields 4,410,000 results when looking for “belonging”.

Okay, Belonging is Important. But What Is It?

This rather quick overview shows two key aspects that our research team was interested in exploring. First, an emphasis in looking at levels of sense of belonging are associated with levels of different outcomes, and how individuals’ identities (e.g. gender, ethnicity, social class) are associated with different levels of sense of belonging, but with less recognition of if and how individuals perceive their identities as important when discussing their sense of belonging. And second, how the levels of sense of belonging are explored asking people to answer the extend of which they agree with the following statement “I belong at [school name]”, yet without recognising that -as such as critical experience- belonging can have different meanings for different people.

Considering these aspects, in our paper published in Social Psychology of Education “Recognizing the diversity in how students define belonging: evidence of differing conceptualizations, including as a function of students’ gender and socioeconomic background”, we aimed to address these aspects, and particularly to understand how HE students define what is to belong for them and if and how they see their identities -specifically gender, social class, and the intersection of both- associated with their definitions. To this end, we conducted online interviews with 36 students enrolled in UK universities.

Belonging: Multiple and divergent definitions.

Students shared different and multiple definitions of belonging, which can be grouped into two different perspectives: belonging as being authentic and belonging as sharing similar experiences with others. Conceptually, both definitions brought up by students fit with the idea of “belongingness” rather than “belonging”. In other words, students spontaneously associated belonging with a state of belongingness rather than a trait (Allen et al., 2021). Interestingly enough, students defined belonging using other concepts that theoretically have been associated with -yet distinguished from- belonging, such as authenticity or similarity.

Although students did not explicitly mention the role of their identities, social class played a role in how they framed and understood belonging. The idea of belonging as being authentic implicitly requires students to feel authentic without negative consequences, which previous literature has shown can be achieved when individuals perceive their identities will be accepted and fit with the organisational culture. For students who defined belonging as sharing similar experiences with others, sharing similarities was an active process for them, highlighting the importance of the group rather than focusing on “just being yourself”. Both perspectives provide insights to understand that the question about belonging, rather than primarily focusing on how certain groups lack belonging, needs to change to understand that identities are context dependent. For instance, being a woman is not directly associated with a lack of sense of belonging. Instead, understanding the experience of being a woman in a particular context (e.g., masculine dominant discipline) can shed light on the particularities of belonging for this group.

Anti-belonging: lack of belonging as a resistance strategy.

Although we aimed to focus on belonging definitions, students explained their conceptualisations highlighting their experiences at university. Hence, the boundaries between definitions and levels were not always clear. However, undoubtedly, experiences of belonging provided the framework from which students defined belonging- either as the basis of their definitions or examples to argue why they defined belonging in a particular manner. Therefore, belonging definitions were contextual and implicitly showed how individuals perceived the group or organisation -and their culture and norms- where they are expected to belong. Indeed, for a group of students at the intersection of gender and social class are women from working-class backgrounds; experiences of exclusion and hostility made them feel that they did not want to belong to the university. Hence, rather than defining belonging, they conceptualised the idea of a "sense of anti-belonging" as they did not want to be part of the institution's culture. This institutional culture was described as segregated, where financial resources were necessary to do well in university and participate in social activities, such as going for a coffee. Hence, belonging is not this unique and always well-received experience. In fact, in some contexts and when intersectional struggles were discussed, individuals did not want to belong. As a working-class female participant- declared:

I almost feel a sense of anti-belonging to university because I HATE [sic] what it has been made to stand for: bigotry almost (…) And as someone who fits outside the typical demographic I feel as though I don’t belong and I don’t even want to belong at this point because I have no desire to be associated with a system that doesn’t condemn well enough something that I so fully disagree with: discrimination.

Next steps: A model to map out belonging definitions, context and identity processes.

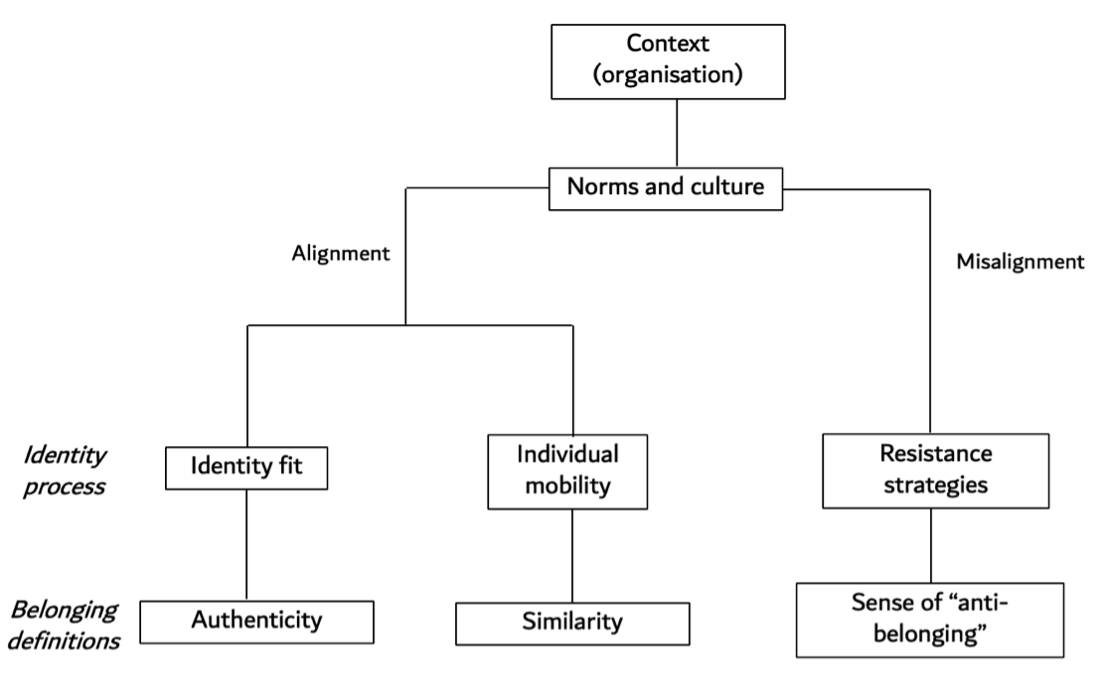

These findings provide important insights about the complexities and nuances of a sense of belonging, and the importance of considering belonging as interrelated with different concepts that could be understood as synonymous but operate as dimensions of belonging. The qualitative approach of this paper allows us to, rather than set final answers, to keep exploring how belonging is a social construct that is context-dependent. Based on the study findings, this preliminary model discusses the idea that belonging is an outcome of the context, particularly organisational norms and culture, the perceived fit with this context, and identity processes put in action to navigate the context. Hence, we propose that to align with the organisation's culture and associated norms promote three different paths: (a) in line with Aday & Schmader (2019) ideas, a perceived identity fit to one social identity can be perceived as a signal to that one's true self will be accepted and valued; (b) to pursue being part of the groups that are perceived as aligned with organisation's norms and culture, emphasising similar experiences with other individuals and group membership, moving to perceived higher status groups, and leading to a positive identity- similar to individual mobility strategies; and (c) to reject organisation's norms and culture, leading to an active rejection to belong to the organisation as a resistance strategy. Each path can be associated with different conceptualisations of belonging.

Fig.1. Belonging definitions, context and identity processes

Fig.1. Belonging definitions, context and identity processes

Understandably, the proposed model is just an initial step to think about belonging as a nuanced and complex concept. We still need to understand (a) whether individuals -not only students- have other conceptualisations of belonging, (b) other identity processes that might explain why individuals define and see belonging from a particular perspective, and (c) if and how the model proposed might represent causal relationships across concepts. Nevertheless, our paper findings contribute to discuss how the definition of belonging as a human motivation might conceal the role of social structures and power relations, reinforcing an individualistic approach to belonging. In other words, a sense of belonging can have individual benefits but collective costs.

References

, . Seeking authenticity in diverse contexts: How identities and environments constrain “free” choice. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2019; 13:e12450. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12450

Photo by Jonas Jacobsson on Unsplash

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in