What is the future of the world’s linguistic diversity?

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Languages are a hallmark of human cultural diversity, with over 7000 recognised languages worldwide. Yet the world’s linguistic diversity is currently facing an even greater crisis than its biodiversity, with around half of all spoken languages considered to be endangered. Each language has a unique history, and each may be subject to particular threats and challenges. In addition to language-specific threats, there may be general factors that impact the vitality of many different languages, but there have been few general analyses of the drivers of language endangerment. Can we adapt the analytical approaches that have been applied in conservation biology in order to characterise current threats to language diversity?

We brought together an international interdisciplinary team of researchers with expertise in linguistics, evolutionary biology, macroecology, mathematics and data analysis, and constructed a global database of over 90% of the world’s spoken languages. We gathered data on factors that influence language transmission (whether a language is learned by children), language shift (factors that cause people to adopt a different language) and language policy (including education and official recognition). For each language, we recorded the current level of endangerment, along with its demographic, environmental, socioeconomic and political conditions

%20copy.jpg)

Languages become endangered not only when populations of speakers are reduced in number, for example through genocide or displacement, but also when people shift from using their heritage language to a different language, for example through colonisation or migration. We characterise the “language ecology” of each language by recording the number of fluent speakers who learned the language as a child, the number of other languages in contact, the proportion of people in the area that use the language, whether the language is used in education and has official national recognition. Language documentation is an important facet of language maintenance and vitality, so we score each language according to whether it has resources such as dictionaries and grammars.

Environmental features have been implicated in language diversity and endangerment, so we include variables that describe whether the language is from a mountainous region or surrounded by rivers, and how much of the year it is possible to grow crops or gather food. We capture the human-modified landscape with the amount and rate of change in farmland, built environments and roads, along with population density and urbanisation. The degree to which the natural environment has been modified is also reflected in number and proportion of endangered species in the surrounding area. We also record indicators of socioeconomic development, such as life expectancy, and income inequality.

All-in-all we have 51 variables representing the current state of each language, aspects of its social, natural and human-modified environment, government policy and economic development. We used a model-fitting procedure to winnow these 51 variables, repeatedly testing the explanatory power of each variable against language endangerment patterns, retaining variables that increase the fit of the model to the data and removing variables that do not, until we are left with a set of significant factors, each of which can help to successfully predict the endangerment level of languages in our database. The result is a fascinating set of predictors that capture some of the current stressors on languages.

Languages decline when people shift to another language and dont use their own “mother tongue” with their children, so the greatest predictor of endangerment is the number of first-language speakers of each language. But we show that it is not contact with other local languages that poses the greatest threat: in fact, the more local languages are in contact with a language, the less likely it is to be endangered. So language diversity itself does not threaten language vitality and persistence. Similarly, landscape features that limit movement between neighbouring populations, such as mountains or rivers, don't influence language endangerment. But a language is more likely to be endangered if other languages in the same area are also endangered, suggesting there are regional factors that can threaten many languages in the same area. One such factor is the density of roads, which facilitate longer-range movement between rural areas and villages to larger towns and cities, potentially prompting the adoption of a regional lingua franca, or a shift to widespread languages of governance and commerce.

Education is implicated in the shift from smaller Indigenous languages to larger regional languages: the more years of schooling, as a national average, the greater the level of language endangerment. This global pattern mirrors results of finer-grained studies that reveal that more time spent in school, being taught in the dominant national language, can lead to loss of Indigenous language competency. This result does not imply that education is bad for speakers of minority languages, but it does ring alarm bells that mainstream education may contribute to language loss. We urgently need more research into the impact of schooling on Indigenous languages, to aid the development of educational programs that allow children to gain the benefits of education without the cost of reduced competency in heritage languages. Bilingual education programs that link community language speakers to children’s schooling may help students retain their own languages while improving engagement with school and success in education.

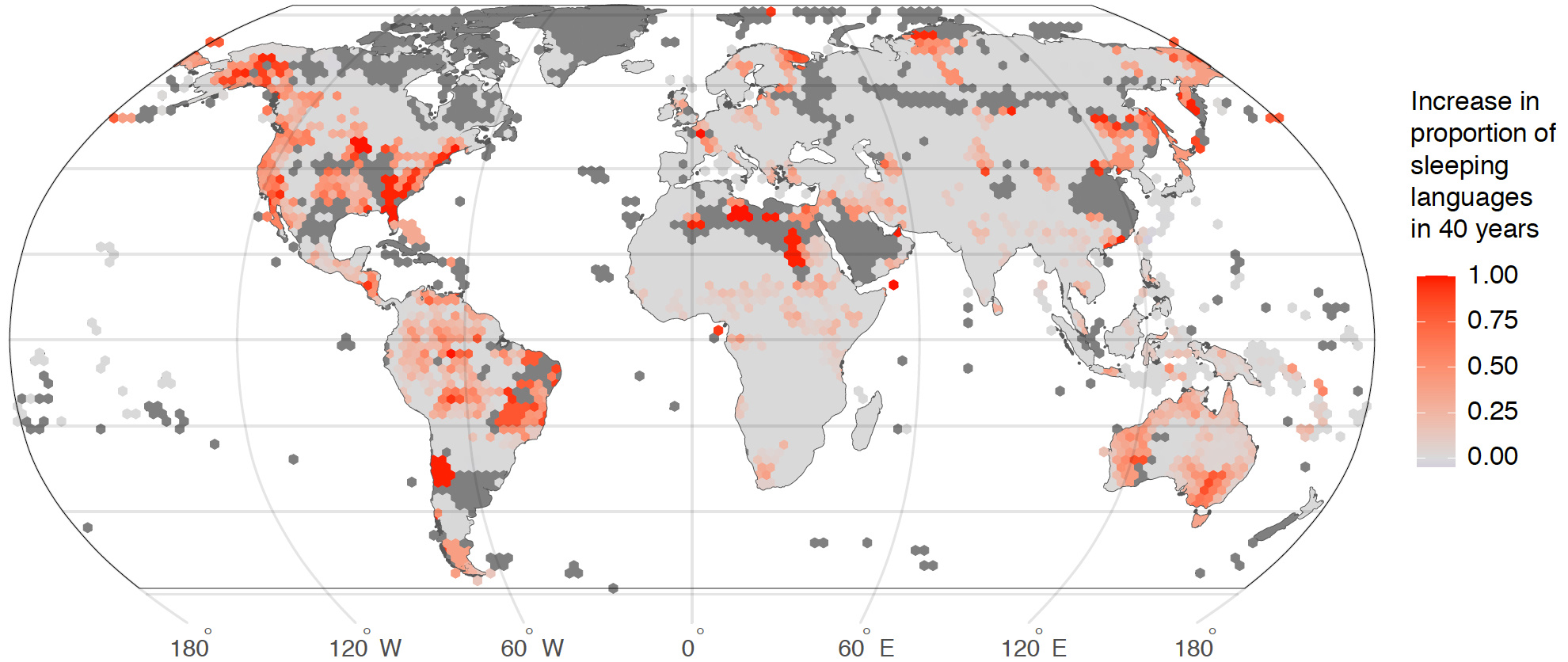

Many of the factors we have identified have predictable patterns of change which we can use to project levels of language endangerment into the future. For example, we can use demographic information to predict future decline in speaker numbers, and use rates of increase in road density in each area to predict how much extra pressure will be put on languages in the future. The results are startling: without intervention, we predict that language loss could triple in the next forty years. By the end of this century, 1500 languages could cease to be spoken.

Model predictions for proportion of languages predicted to be no longer spoken (Sleeping, EGIDS ≥ 9) in the next 40 years. Each hexagon represents approximately 415,000km2. Language distribution data from WLMS 16 worldgeodatasets.com. Figure from: Bromham L, Dinnage R, Skirgård H, Ritchie AM, Cardillo M, Meakins F, Greenhill SJ, Hua X (2021) Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity Nature Ecology & Evolution https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-021-01604-y

Why should we care about language loss? Losing a language represents the loss of a unique history and a treasure trove of cultural knowledge. Each language is a tribute to the creativity and inventiveness of human minds, a beautiful and fascinating solution to complex communication challenges. Languages carry irreplaceable information about human history and diversification, which can trace patterns of migration and cultural exchange even where other historical evidence is lacking. Most importantly, for many people, language symbolises cultural identity and belonging. Many groups mourn the decline of unique languages and yearn for competency in languages no longer spoken. Around the world, people are working to revitalise endangered languages as a way of strengthening culture and connecting people to their heritage.

While the predictions for language loss are grim, these are the expectations in the absence of any active intervention to change current trajectories. It’s not too late to make an impact: many of these endangered languages still have fluent speakers, but we need to act swiftly to support communities to nurture living languages, and encourage children to learn them and use them within school, at home, and in the wider community. 2022 marks the beginning of the UNESCO International Decade of Indigenous Languages, which is a chance to celebrate, revitalise and protect global language diversity.

For more information see: Bromham L, Dinnage R, Skirgård H, Ritchie AM, Cardillo M, Meakins F, Greenhill SJ, Hua X (2021) Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity Nature Ecology & Evolution https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-021-01604-y

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in