Which learning strategies work best, and when?

Published in Neuroscience

Learning strategies: a synthesis and conceptual model

In this review, Professor John Hattie and Gregory Donoghue, from The University of Melbourne in Australia, assessed the strength of evidence behind various learning strategies. They combined and analysed a variety of meta-analytic studies into the effectiveness of different learning approaches.

Although the authors had the original aim of ranking the learning strategies according to their efficacy, the large variability in effect size for even a single strategy made this approach ineffective. According to the authors the variability resulted from inconsistencies as to when during the learning process the strategy was applied.

Instead Hattie and Donoghue developed a model that classified each of the 302 learning strategies into one of 10 categories. Six of these could be considered learning strategies, while the remaining four are factors that influence learning outcomes, rather than learning strategies per se.

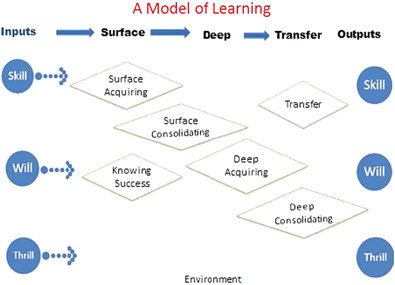

The basic structure of the model has three student-centered

inputs that influence the learning process; the same factors are also affected

by learning and so double as outputs in the model. These factors are:

1. The student’s natural ability to learn (skill)

2. Their motivation (thrill)

3. Their disposition towards learning (will)

The fourth factor cited as influencing learning was the learning environment. These four factors act at a global level to affect any or all of the strategies that comprise the learning process.

In categorising the learning strategies, Hattie and Donoghue distinguish between surface, deep, and transfer phases, with surface and deep phases each being divided into acquisition and consolidation components. The authors acknowledge that the lines between these categories are somewhat blurry, and also stress that there is no strict chronological order to the three learning phases: surface and deep acquisition could occur at the same time, for example. Nevertheless the progression from surface to deep to transfer is real: isolated facts are remembered (surface), then integrated with or separated from each other conceptually (deep), and finally the deeper knowledge is used in a way that exhibits the learning outcome (transfer). The sixth category of learning strategy, titled “knowing success”, consists of ways by which students are made aware of their learning goals. This allows the student to set goals and select learning strategies that will best achieve the outcomes.

Amongst the most effective learning strategies for learning achievement was having a clear understanding of the target outcome. Reshaping newly learned information and integrating it with prior knowledge were highly associated with achievement, and strategies for learning transfer — for example, using knowledge of arithmetic rules to solve word-based problems — also seemed particularly effective. Aspects of student collaboration also scored well, with classroom discussion and seeking help from peers both linked strongly with high achievement scores. Although not a learning strategy, student self-belief was also valuable.

Hattie and Donoghue conclude by advocating for a holistic approach to improving learning: efforts should be made to modulate student-oriented factors (skill, will and thrill), which can then enhance outcomes achieved by applying the learning strategies; students should be made aware of what a successful outcome is, so that they can set goals and choose the most appropriate learning strategies; and the appropriate strategy should be chosen based on the desired learning outcome (surface or deep) and the stage of learning the student is at (acquisition or consolidation).

Follow the Topic

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in