Who's a Bonehead? Novel Insights into Evolutionary History from Reptilian Skull Roof Structure

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Why are terrestrial vertebrates so highly diverse? In times of anthropogenic change and mass extinctions, this key question to evolutionary research is more relevant than ever. We often attribute this phenomenon to modifications in accordance with different environments and lifestyles. However, it is not always easy to reconstruct from the fossil record how historic key events determined the destinies of entire lineages millions of years ago. Therefore, 160 years after Darwin's theory of evolution, our understanding of certain evolutionary mechanisms remains incomplete.

In order to better understand the complex interrelations between vertebrate lifestyle, form, and evolution, we looked into the skull roof structure of squamate reptiles – i.e., lizards and snakes. We wanted to understand to what extent their bone structure reflects certain lifestyles. Although many of these reptiles use their skulls as a digging tool, this question has never been systematically investigated. In our paper First Evidence of Convergent Lifestyle Signal in Reptiles Skull Roof Microanatomy, we therefore employed computer simulations to reconstruct the evolution of a specialised burrowing lifestyle over a period of 240 million years. Remarkably, we found that burrowing evolved independently in 54 squamate lineages. These reptiles are therefore particularly well suited as a model system for the study of convergent evolution.

Scincoid lizards, such as this representative from the Australian east coast, are among the most diverse squamates – both ecologically and taxonomically. Nonetheless, we were surprised to identify 20 independent acquisitions of a specialized burrowing lifestyle in this clade alone. Photo by Roy Ebel.

In the second phase of our study, we compared the skull roof structure of lizards and snakes in accordance with their lifestyles. To this end, we made use of high-resolution computed tomography (micro-CT) for the 3D visualisation of bone tissue and employed a new, effective protocol for data analysis. Doing this, we achieved a large sample size, allowing us to draw conclusions about the entire squamate reptilian clade with over 11,000 species. We found that burrowing lizards and snakes have repeatedly evolved a particularly dense and compact skull roof in independent evolutionary processes. We further identified typical proportions of both the skull and between the skull roof bones as convergently evolved modifications associated with this lifestyle.

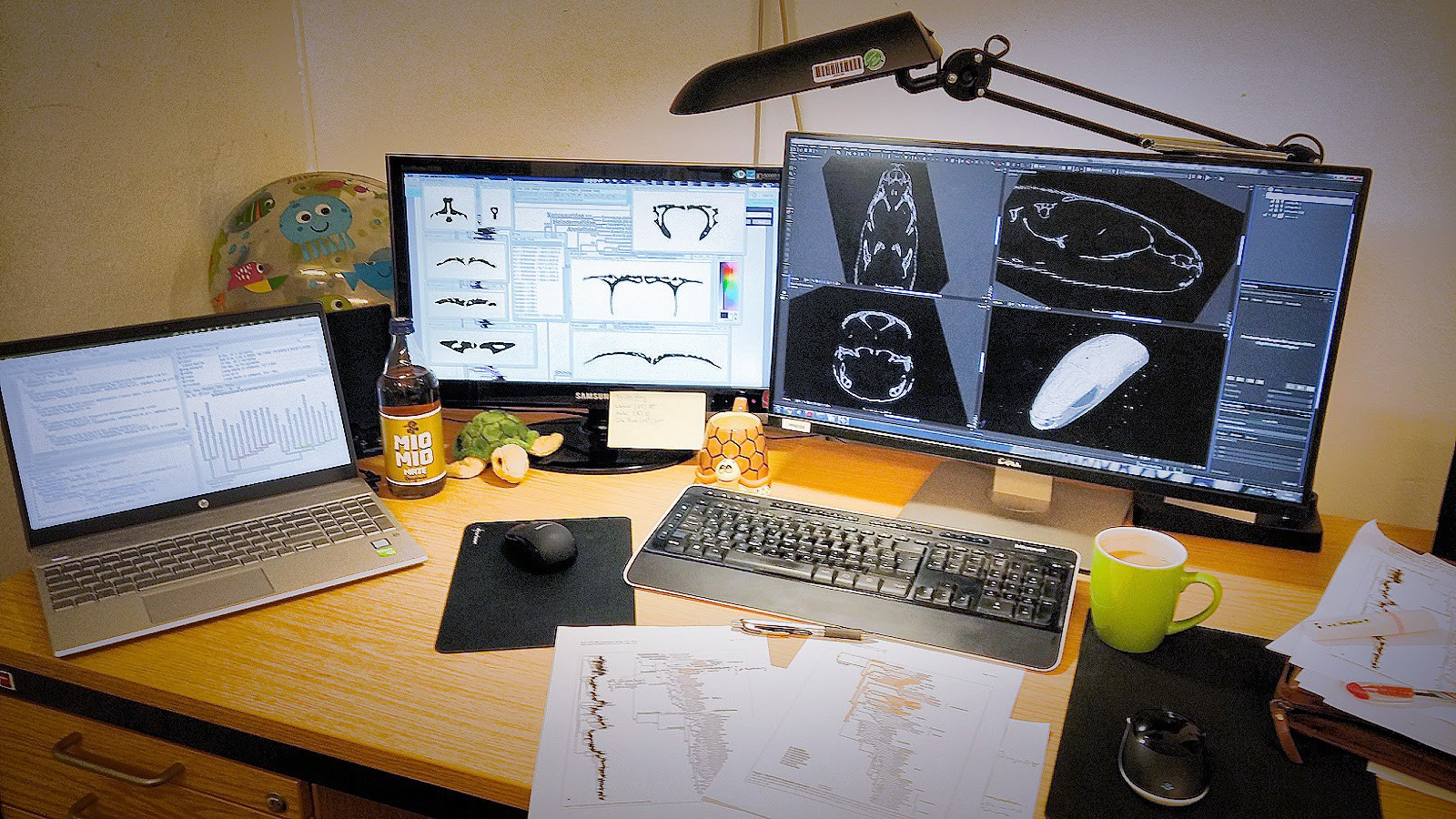

This desk at the CT-Vis-Lab of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin says quite a bit about our working routine. From right to left: VG Studio MAX for processing 3D-volumes acquired with µCT, ImageJ for processing extracted slices, and R-Studio for the analysis of convergence and lifestyle signal. As a coincidence, the stages of data reduction correlate with decreasing screen size. ...and who would have thought that this is how a biologist's workspace may look like? Photo by Roy Ebel.

In our study, we present a novel case of convergent evolution: in different lineages, very similar structures have independently evolved in response to a common lifestyle. Such similarities reflect a certain function, in this case burrowing, and may therefore provide little information on the phylogenetics relations between the considered taxa. Nonetheless – or precisely therefore, the knowledge of these processes is of outstanding importance: by means of skull roof structure, we can now reconstruct the lifestyle of reptiles that became extinct millions of years ago. Our findings thus cast completely new light on the evolutionary history of certain lineages. This may particularly apply to snakes, for which both an aquatic and burrowing origin have been controversially discussed for decades. Our work now adds to a growing body of evidence for the latter. Having said this, our findings may also have important implications beyond squamate reptiles. A burrowing lifestyle has likely played a key role in the evolutionary history of turtles and certain amphibians. Recent studies even suggest that the mammalian stem lineage may not have survived the largest mass extinction in earth's history at the end of the Permian about 250 million years ago without adopting a burrowing lifestyle. It is therefore invaluable to understand such historical lifestyle transitions.

This little critter is a rare burrowing gymnophthalmid lizard from Brazil, which quickly became a lab favourite for its happy smile. We were able to include the specimen in our dataset due to a loan from the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH R64876). In total, our dataset comprises specimens from 13 herpetological collections worldwide. Photo by Roy Ebel.

Should our work have sparked your interest in the fascinating field of squamate skull morphology and its implications for their ecology and evolution, you may be pleased to hear that we uploaded the µCT-scans employed in our study into the Data Repository of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. They will thus be available for future research projects worldwide.

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Biology

This is an open access journal publishing outstanding research in all areas of biology, with a publication policy that combines selection for broad interest and importance with a commitment to serving authors well.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Organoids: advancements in normal development and disease modeling, and Regenerative Medicine

BMC Biology is calling for submissions to our Collection on Organoids: advancements in normal development and disease modeling, and Regenerative Medicine. This Collection seeks to bring together cutting-edge research on the use of organoids as models of normal organ development and human disease, as well as transplantable material for tissue regeneration and as a platform for drug screening.

Studies can be based on organoids derived from either induced pluripotent stem cells or tissue-derived cells (embryonic or adult stem cells or progenitor or differentiated cells from healthy or diseased tissues, such as tumors).

We welcome submissions focusing on studies investigating the mechanisms of self-organization and cellular differentiation within organoids, and how these processes recapitulate human tissue architecture and pathology. We are especially interested in studies addressing the issues of improving tissue patterning, specialization, and function, and avoiding tumorigenicity after transplantation of organoids. We will also consider studies that demonstrate the application of organoids in personalized medicine, such as drug screening, toxicity testing, and the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

We are interested in studies focusing on the refinement of methods to enhance the fidelity and functional maturity of organoids, especially those integrating organoid models with cutting-edge technologies such as advanced imaging, single-cell and spatial omics, microfluidic chip systems and bioprinting.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being.

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 15, 2026

Environmental microbiology

BMC Biology is calling for submissions to our Collection on Environmental microbiology. Environmental microbiology is a rapidly evolving field that investigates the interactions between microorganisms and their surrounding environments, including plants, soil, water, and air. This area of research encompasses a diverse range of organisms, from bacteria and protists to extremophiles, and seeks to understand their roles in various ecological processes. By examining microbial communities and their functions, researchers can gain insights into plant-microbe interactions, biogeochemical cycles, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem dynamics. Furthermore, the study of the microbiome in different habitats is crucial for understanding biodiversity, ecosystem resilience, and the potential applications of microbes in environmental remediation. Advancements in molecular biology and bioinformatics have significantly enhanced our understanding of microbial ecology and the intricate relationships that underpin environmental systems. Understanding these interactions is essential for addressing pressing global issues such as climate change, pollution, and ecosystem degradation to develop sustainable strategies for environmental conservation and restoration.

Potential topics include but are not limited to:

Plant-associated microbes in sustainable agriculture

Microbiomes and symbioses in aquatic ecosystems

Microbial contributions to biogeochemical cycles

Community structure and dynamics in soil, water, air, and extreme environments

Extremophiles and their ecological significance

Pathogen Ecology

Host-Microbe Environmental Interactions

Effects of climate change and environmental stressors on microbial communities

Methodological Advances in environmental microbiology

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 6: Clean water and Sanitation, SDG 13: Climate Action, SDG 14: Life Below Water, and SDG 15: Life on Land.

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 25, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in