"Towards a Universal Economy based on Human Rights: concepts, fundamentals and challenges", in Italian

Published in Social Sciences

Introductory paper by Prof. Francesco Vigliarolo, Director of the UNESCO Chair, in the biennial Conference "Towards a Universal Economy based on Human Rights" organized by the UNESCO Chair in "Economic Systems and Human Rights" of the UNLP, Palacio del Monte Frumentario, Assisi, October 16-18, 2025.

Full text of the conference

Towards the process of economic positivization

To understand and reflect on the relationship between economics and human rights, we believe it is absolutely essential to introduce the process of economic positivization that has occurred over the centuries. From its birth in antiquity to the present day, economics has undergone a process that has completely stripped it of any ethical, cultural, social, or even transcendental dimension, to become a science on a par with the so-called exact sciences, such as physics, biology, and so on; based almost exclusively on the use of mathematical logic and statistics. From a conception of man as striving for socialization (Aristotle, one of the founders of the concept of economics along with Xenophon), we have ended up speaking exclusively of a man striving for market exchange, the so-called homo economicus. Furthermore, from man as a bearer of rights, we have ended up speaking of man as a bearer of interests, the only ones that, first with mercantilism and then with Smith, matter in explaining economic systems even today.

Thus we arrive at the end of the 19th century, an era characterized by the crisis of the social sciences, as Husserl defined it, when the distinction between positive economics and normative economics was born, thanks to John Neville Keynes, father of the more famous John Mynard. In an 1891 text on the method of political economy, he defined positive economics as "the description of how an economic system works 'as it is'"; and normative economics as "the assessment of what is desirable, its costs and benefits." Milton Friedman later echoed this definition when he argued that positive economics should be treated on a par with the natural sciences, that is, it is an exact science like physics. Indeed, he argued that positive economics is, in principle, independent of any ethical position or normative judgment; it studies "what is," not "what ought to be." Its task is to provide a system of generalizations that can be used to make correct predictions about the consequences of any change in circumstances. Its functioning must be judged by the accuracy, scope, and consistency of the predictions it provides with experience. In short, positive economics is, or can be, an "objective" science, in exactly the same sense as any physical science. Under these assumptions, the eradication of the social sciences is thus definitive.

Mathematical reasoning aimed at maximizing personal interests, grounded in extreme materialism, has pervaded all spheres of social life, even undermining interpersonal relationships. Everything has become a matter of negotiation. This process has undoubtedly intensified since the fall of the Berlin Wall, which left capitalism and the process of capital accumulation, now in its financial phase, as the sole dominant economic model, permeating all spheres, including feelings and behaviors.

Economic Financialization

Today, individual interests, completely detached from any cultural considerations, are reaching their peak with the emergence of what is called the financialization of the economy, which began in the 1970s. According to some, due to the declining rate of profit and the end of the United States' golden age, large American corporations sought enormous profits on the financial markets through the buying and selling of the dollar, which Nixon had separated from its gold standard.

We live in the full Krematist era, predicted by Aristotle himself, in which everyone gambles their fate at the roulette of international stock markets, transforming the global economy into a gigantic casino, as Tonino Perna argues. Just think of the phenomenon of cryptocurrencies, with millions and millions of dollars at stake every day without any production system behind them.

Financialization, however, is now a consolidated process; 95% of financial values have no relation to goods and services. To understand the change in pace that occurred precisely at the turn of the 1970s and 1980s, for example, between 1977 and 1998, global currency transactions grew from $18.3 billion per day in 1977 to $1.5 trillion. From 1977 to 1998, the ratio of annual foreign currency money value to foreign exports increased from 3.51 to 55.97. The ratio of central bank reserves to daily foreign exchange assets fell from 14.5 to 1. In 1995, financial assets represented 76 times more resources than global trade in goods and services: for every dollar spent on trade, $75 was invested in financial assets. Today, we're talking about a spread of 1 to 95, although these measurements are very difficult to sustain given the amount of currency in circulation. It's also estimated that 10% GDP growth corresponds to a 30% increase in financial values. We're therefore witnessing the absorption of a powerless mass of small investors by a financial oligarchy—high finance, as Polanyi defined it. Furthermore, they're swallowing up state-owned sectors such as pensions, healthcare, railways, and so on, reducing their rights or subordinating them to financial logic.

We're also witnessing the phenomenon of corporate impersonality and the loss of industrial identity, with companies engaging in financial speculation. This is why Alain Minc writes: "Today, it's not those who work who are rich, but those who work with money." In other words, since the 1970s, we've seen a growth in global monetary wealth, but also an increase in poverty, even in the so-called Nordic countries, as Daly and Cobb observed in a US study. GDP growth is no longer in line with growth in real well-being.

Some data in the world: social and climate crisis

According to the ILO, in recent decades we have seen a structural increase of approximately 2% in global unemployment, which equates to millions of people losing their right to work. The number of people living on less than $6.85 a day, approximately $250, is now 3.2 billion, almost a third of the world's population. This figure has remained stable since the 1990s and is failing to decline (Oxfam data 2025). Added to this are over 7 million citizens worldwide who die from economic pollution. 700,000 in Europe. 70,000 in Italy. And many, far too many, are dying from hunger all over the world. Not because there is no food, but because of the dysfunction of the dominant market, lacking rules and protections for rights. The wealth of billionaires globally has increased at unprecedented rates (e.g., according to Oxfam, growth of $2 trillion is expected in 2024). The richest 1% of the world's population holds a similar share of wealth to the remaining 44% of humanity, highlighting a massive imbalance. Forced labour is the second most widespread illicit economy in the world. It is estimated that, globally, forced labour generates annual profits for traffickers of $236 billion (2025 data). In low- and middle-income countries, informal employment remains the most common form of labour market participation. Women continue to earn approximately 20% less than men for the same job.

The climate crisis and extreme weather events disproportionately affect the poorest communities, directly threatening their livelihoods (agriculture, water resources) and continuously forcing migration. One in five people worldwide is highly exposed to the risk of climate disasters.

Armed conflict leads to massive economic violations. For example, in conflict areas, access to medical services is drastically reduced, and pregnant women face maternal mortality rates up to 60% higher than average.

Disparities in access to education and health services remain a key indicator of economic and social rights violations.

In summary, the violation of economic human rights is seen by major organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Oxfam as the direct result of regressive economic policies, systemic inequalities, and the lack of adequate global governance to protect the real economy and equity.

We are undoubtedly living in an era of turbocapitalism, where, according to Edward Luttwak, we are experiencing a process of acceleration and deregulation of the global economic system. We are also experiencing the rise of state capitalism, where law is subservient to economic reason, as Chomsky states. Where societies have become homogenized, they are progressively losing their creativity. And societies lacking creative capacity are destined to disappear.

The last few centuries of economic thought have therefore seen a complete loss of cultural and normative reference for this science, that NOMOS, which was the second Greek word from which the word economics derives, along with OIKOS, house. For these reasons, we must rediscover a global NOMOS. As are human rights. Rules that aim to promote the common good, not defend personal interests.

This can refer to the beautiful 1948 Charter. A Charter that establishes that all men and women are equal, not in the sense that everyone must conform, but that everyone is born with the same rights and must be treated equally. White, black, red, yellow, we all belong to the same common home, we could paraphrase to the global economy. Article one, in fact, invites us to act in a spirit of fraternity. That's why we chose Assisi, the symbolic city of world-fraternity founded by Saint Francis.

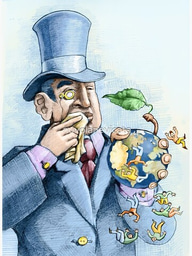

Human Rights: the way to universalize the economy and defending from dominant economic

While human rights were also born to defend people from the abuses of states, today we must defend ourselves from dominant economic systems. A great human rights advocate and scholar like Antonio Papisca, whom I always like to remember, said that where there is a dimension of being, there is a right. They can be also considered the universal essence of that human and natural substance, as Polanyi called it, of our humanity, which the economy must advance if we want to once again be fully subjects of rights. Otherwise, we will transform our planet into a war zone like wolves and lambs, where we sacrifice entire generations in the name of god profit.

New social practices

Between the 1980s and 1990s, according to an analysis by Rifkin (1995), we also witnessed the exponential growth of bottom-up, socially-driven economies throughout the world, intervening in various sectors, often providing solutions that the two dominant systems, the state and the market, have left unsatisfied. Called social, solidarity, civil, popular, and other economics, they bring with them characteristics such as democratic participation as a prerequisite for a true connection between society and the economy, carrying out activities of general interest.

In the European Union alone, these forms of economy involve over 2.8 million individuals and employ approximately 13.6 million people. The social economy ecosystem, as it is often called, has a turnover of almost €1 trillion (2021 data), a value comparable to that of the European automotive sector. And according to the Commission, it can reach up to 10% of GDP in some countries.

These experiences demonstrate something important: that individual freedoms are not at odds with the common good, or with common happiness. Because it is impossible to separate individual happiness from community identity. This has been the greatest temptation we have experienced in recent centuries: the constant ideological dichotomy based on the contrast between freedom and the common good. Also because after the fall of the Berlin Wall, turbo-capitalism is accelerating further, seeking to impose increasingly unregulated models. Just look at the forms of anarcho-capitalism still in vogue today in some South American countries, where the state is seen as the enemy to be fought. As if caring for the common good—food, education, the right to work, inclusion, infrastructure, the environment, and so on—were now a crime and a limitation of individual freedoms. But let's be careful, for if freedoms aren't accompanied by an ontological dimension, they risk leading us into the abyss. No one questions them, but increasing the ontological dimensions means increasing individual freedoms themselves. The two dimensions feed each other. Without education, food, and healthcare, no society is free.

Ontological reason vs utilitarian reason

These experiences alone, perhaps, are not enough. They are still too small to dent a system also made up of economies of death, of wars, which also serve the needs of economic power groups. To change this trend, we undoubtedly need to intervene at various levels—local, national, and international—but first and foremost, we need to address the dominant theoretical models. Individual interest is undoubtedly to be considered a primitive stage of economics. We need an economy that counters utilitarian reason with what we call an ontological reason of peoples. Because every people has, first and foremost, its own demand for rights that it must be able to pursue. And all peoples have their demand for universal rights.

This is why our UNESCO Chair was born. And this Conference today too. Because we need to build a universal economy that allows everyone to be. We can no longer afford an economy that serves the interests of a few. An economy that oppresses us, the enemy of citizenship, that is leading us to destruction; which has annihilated the individual, powerless before a materialistic structure that is devouring him.

We are subjects of rights (and duties), not instruments of consumption. We need to build another economy, intersubjectively, because the process of forming social knowledge is intersubjective; one that promotes new practices that change the current global structure. We also need to address the law of supply and demand, based on price and quantity, which in our opinion is also primitive. Likewise, the micro and macro dimensions, now interpreted solely by mathematical, positivist variables, no longer fully reflect reality. This is why we now also speak of a meso-economy, a space where intermediate bodies (social movements, social economy organizations, SMEs, etc.) define territorial strategies and reorient the global economy. Where people, values, ideas, societies and environmental, not capital, are put back at the center.

Peripheries at center: toward an economic socialization on human rights

Pope Francis urged us to leave the centers and move toward the periphery. Perhaps it's time to transform the peripheries into centers, because where there's a single man or woman in need, there's a center. We must go against the grain, as did Francis, the poor man of Assisi, who stripped himself of material riches to be fully enriched by spiritual riches. Walras, a famous classical economist, also spoke of the dichotomy between spiritualism and materialism, arguing that the former enriched law and led to social justice, while the latter only led to material wealth without justice. Undoubtedly, the theoretical foundations of economics must be re-established so that it is as integral as human rights, oriented toward the common good, where individuals are strengthened. Because its opposite is not the same thing.

With these objectives, the Conference offers two lectio magistralis, one by the Bishop of Assisi, Monsignor Domenico Sorrentino, and the other by Prof. Stefano Zamagni, a world-renowned economist. And four roundtables on society, finance, environment, and education, with the participation of academics, experts, professionals, and judges. My only hope is that this may be the beginning of a journey that will take us far, leading us to build together a universal economy based on human rights with concrete practices that will become global. This is no easy battle; we are called to defeat a new Goliath. But perhaps the courage to face it shows us how fragile a system is that is not founded on respect for men and women and for creation.

Finally, I thank all the Sponsors—the Umbria Region, the Municipality of Assisi, the Umbria Chamber of Commerce, and the University of Perugia—for their invaluable collaboration. The participating movements and institutions, as well as the other participating UNESCO Chairs, are also grateful. I extend my heartfelt thanks to all the speakers and participants will contribute, as well as to the Authorities who attended, along with the Franciscan Fathers, to whom I extend a special affection. And last but not least, I thank the National University of La Plata for giving me the space to promote these issues for many years, and to the professors of our UNESCO Chair who have dedicated themselves for years to working together with different specializations toward this common goal. These are topics overlooked in Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations," the father of classical political economy, which brings back to the centre of the debate that the true wealth of countries, perhaps, lies in the full exercise of human rights and not in the accumulation of financial capital, if we are not to jeopardize the present and future identity of our peoples. Because we need to live and resocialize values, not interests, and human rights are those universal values around which we can build a process of WORLD ECONOMIC SOCIALIZATION, that allows us to relate to each other as friendly peoples and not as businessmen.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in