A review of the RTS,S malaria vaccine - efficacy, impact and mechanisms of protection

Published in Microbiology, General & Internal Medicine, and Immunology

Explore the Research

The RTS,S malaria vaccine: Current impact and foundation for the future

The RTS,S malaria vaccine is a new starting point for combating malaria and is a foundation for future vaccines.

The RTS,S vaccine has recently been recommended for implementation as a childhood vaccine in regions with moderate to high malaria transmission. What do we know about how it works and how long protection lasts, and how can we build on RTS,S to develop more protective and long-lasting vaccines?

Malaria is a major global health burden responsible for >240 million episodes of clinical illness and >600,000 deaths annually, particularly in sub-Saharan African children under 5 years of age. More than 90% of malaria infections are caused by Plasmodium falciparum. The disease also has serious consequences for education, equity and economic development in endemic countries.

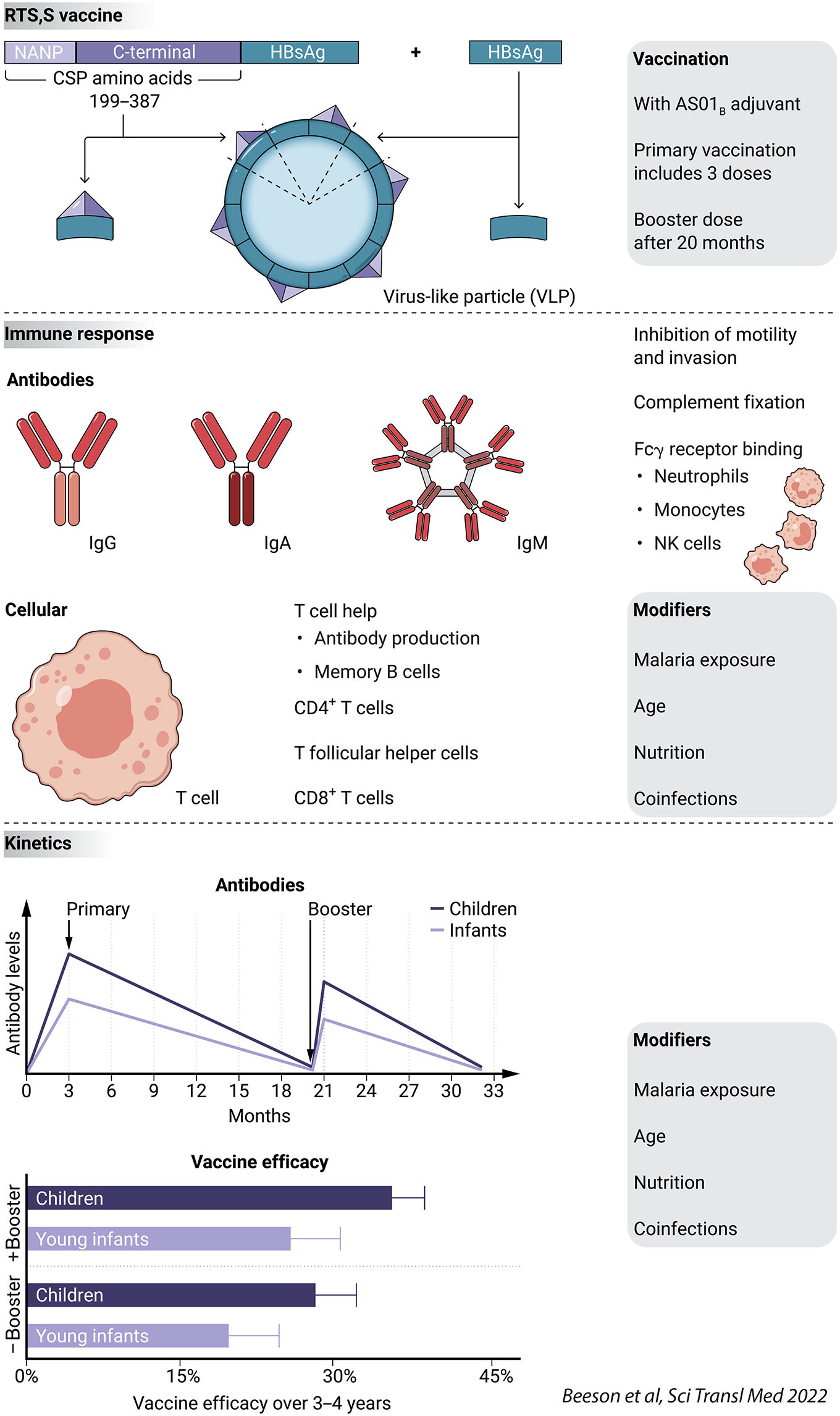

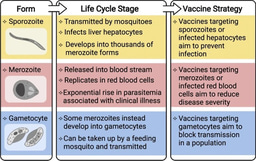

Global progress in reducing malaria has stalled since 2015, highlighting the need for new interventions and tools such as vaccines. Therefore, the first recommendation by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2021 to implement the RTS,S malaria for widespread use in young children was an important milestone. RTS,S is a virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine based on the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP), including immunodominant antibody epitopes and T-cell epitopes (Figure 1).

Although promising, the RTS,S vaccine does have important limitations. Vaccine efficacy is modest and short-lived. In children aged 5-17 months efficacy was 55% over the first 12 months after the primary course of vaccination (3 doses). Given the rapid waning of protective immunity, a booster dose is recommended 18 months after completing the primary immunization. When a booster dose was given, the RTS,S vaccine conferred 36% vaccine efficacy against symptomatic malaria and 29% efficacy against severe malaria over 4 years in the phase 3 trial. RTS,S is currently only recommended for young children living in areas with moderate to high malaria transmission, most of whom are in sub-Saharan Africa, with the first dose commencing at age 5 or 6 months and a booster administered at age 2 years. No malaria vaccine is currently recommended for children outside this age range, adolescents, or adults who are at risk of malaria.

The vaccine and how it works

The RTS,S vaccine encodes a part of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP), which is the major surface antigen of the sporozoite stage, fused to the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg); See Figure. The vaccine is produced as a virus-like particle (VLP), which comprises the CSP-HBsAg fusion protein and HBsAg, and is then formulated with the adjuvant AS01B. NANP is a repeating amino acid sequence of asparagine-alanine-asparagine-proline. Antibodies induced by the RTS,S vaccine mediate protection against malaria.

Precise mechanisms of immunity are not clearly defined, but are thought to involve Fc-receptor mediated functions (through neutrophils, monocytes, and NK cells), complement fixation and activation, and inhibition of sporozoite motility and invasion of host hepatocytes. Specific CD4+ T cell responses and phenotypes, including T follicular helper cells, are important to support antibody generation and secretion and B cell memory, and support innate cell responses. CD8+ T cells may contribute to immunity, but their role has not been established.

The RTS,S vaccine was evaluated in a multicenter phase 3 vaccine trial in two age groups of African children in malaria-endemic regions: young children (ages 5-17 months) and young infants (ages 6-12 weeks). Vaccine efficacy was higher in young children than young infants, waned over time, and was improved by administration of a fourth booster dose 18 months after the third vaccine dose. Vaccine efficacy is shown for the RTS,S vaccine administered as a primary 3-dose vaccination with the booster dose at 18 months (plus booster), or for the primary 3-dose vaccination course only (no booster). Vaccine efficacy over the first 12 months was 55%. Antibodies, especially functional activities, wane substantially within 18 months after completion of the primary 3-dose vaccination course; the fourth vaccine dose boosts antibodies, but below the magnitude observed after the primary vaccinations. Malaria exposure and age can influence vaccine responses and efficacy; nutritional factors and other infections may influence vaccine responses but their roles have not yet been defined.

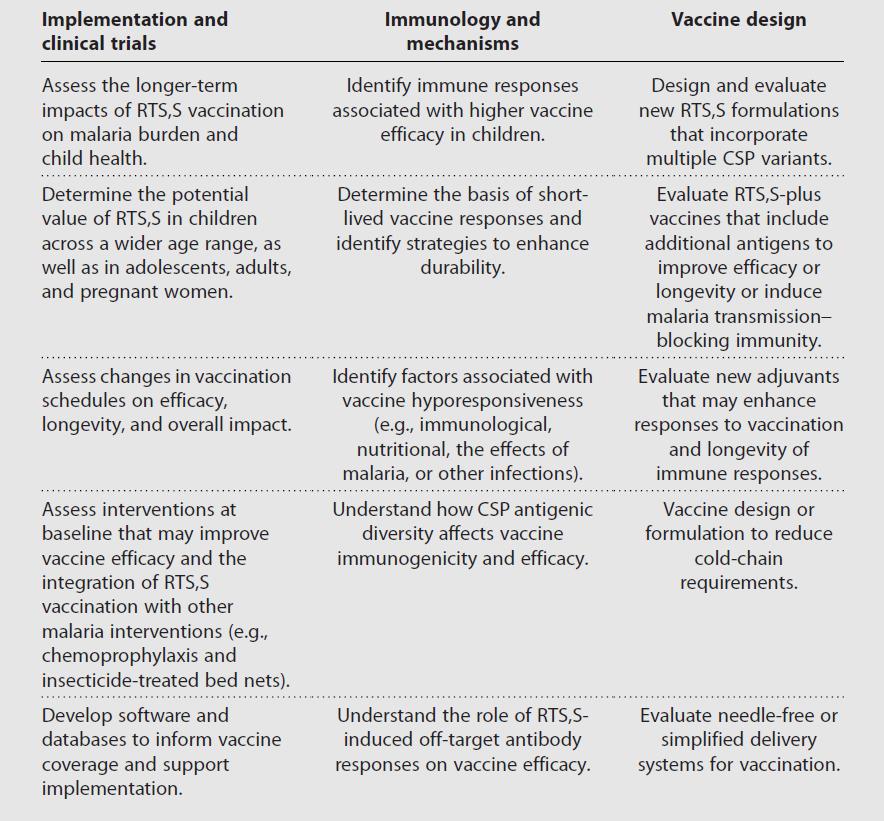

Research priorities for RTS,S and malaria vaccines

The recommendation of implementing RTS,S vaccination in young children represents a major step towards reducing the global burden of malaria. Future research on improving the RTS,S vaccine is a priority across several broad areas (see Table), and will also be relevant to informing the development of next generation vaccines.

See brief video summary of RTS,S here: The RTS,S malaria vaccine: Why has it taken so long and what does it mean for malaria elimination? Liriye Kurtovic discusses the significance of the WHO announcement recommending the RTS,S vaccine, why it has been such a long road to achieving a malaria vaccine and what are the priorities for the future.

For a detailed review and discussion of RTS,S:

Beeson JG, Kurtovic L, Valim C, Asante KP, Boyle MJ, Mathanga D, Dobano C, Moncunill G.

The RTS,S malaria vaccine: Current impact and foundation for the future. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Nov 16;14(671):eabo6646. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abo6646.

Related posts on RTS,S:

https://microbiologycommunity.nature.com/posts/rts-s-the-first-malaria-vaccine-what-mediates-protection-and-how-long-does-immunity-last

Follow the Topic

Ask the Editor - Immunology, Pathogenesis, Inflammation and Innate Immunity

Got a question for the editor about the complement system in health and disease? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in