RTS,S, the first malaria vaccine - what mediates protection and how long does immunity last?

Published in Microbiology, General & Internal Medicine, and Immunology

Currently, RTS,S is the only malaria vaccine that has completed phase III clinical trials in African children, and in October 2021 the WHO recommended widespread use of RTS,S among children in sub-Saharan Africa and other regions with moderate to high P. falciparum malaria transmission.

Modest vaccine efficacy and short durability for RTS,S

RTS,S demonstrated only modest efficacy with relatively short longevity. In young children aged 5–17 months, RTS,S vaccine efficacy against clinical malaria was ~50% over 18 months of follow-up. Efficacy waned quickly such that there was little or no significant efficacy after 18 months. When a booster dose was given at 18 months, vaccine efficacy over 3-4 years was 36%. Notably, other vaccine candidates tested in clinical trials have either failed to confer significant protection in target populations of malaria-exposed individuals or have not yet demonstrated higher efficacy or greater durability than RTS,S in young children that is reproducible in multiple trials. So while RTS,S is imperfect, there is no vaccine on the horizon that is markedly superior.

What protective immune responses are induced by RTS,S?

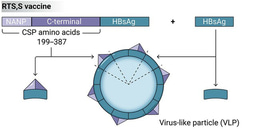

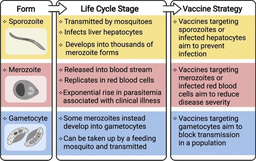

The RTS,S vaccine is based on the circumsporozoite protein (CSP), a major surface-expressed antigen on the sporozoite stage of P. falciparum, and antibodies are the main mediator of vaccine efficacy. However, the mechanisms of action of these antibodies are not fully understood, especially among children. This lack of knowledge impedes progress to improve on RTS,S and constrains the development of more efficacious second-generation vaccines. Recent studies have demonstrated that antibody interactions with Fc-receptors on immune cells can play important roles in mediating immunity against sporozoites, including opsonic phagocytosis by neutrophils and monocytes and cellular cytotoxicity by NK cells.

We investigated the induction and longevity of functional antibodies in a phase IIb trial of RTS,S among Mozambican children aged 1-5 years old. We found that RTS,S vaccination induced specific IgG with FcγRIIa and FcγRIII binding activity and promoted phagocytosis by neutrophils, THP-1 monocytes, and primary human monocytes, neutrophil respiratory burst activity, and NK cell activation, suggesting these mechanisms could be contributing to vaccine efficacy.

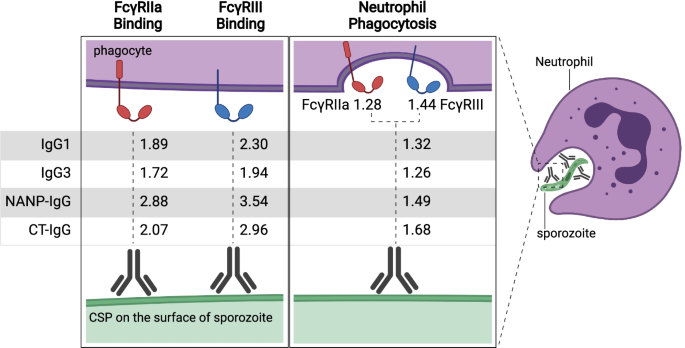

Biostatistical modelling suggested IgG1 and IgG3 contribute in promoting FcγR binding and phagocytosis, and IgG targeting the NANP-repeat and C-terminal regions of CSP were similarly important for functional activities

Figure Legend: Antibodies against CSP opsonise sporozoites and interact with FcγRs to promote phagocytosis, which is predominantly mediated by neutrophils. Rate ratios are shown for the relationship between IgG subclasses and IgG to NANP-repeat and C-terminal domains of CSP, and antibody functional activities (FcγRIIa or III-binding and neutrophil phagocytosis). Rate ratios are also shown for the relationship between FcγRIIa and FcγRIII binding and neutrophil phagocytosis. Values are rate ratios and represent the percent change in participants’ antibody functional activities for each unit increase in IgG reactivity or FcγR binding. p≤0.001 for all rate ratios except neutrophil phagocytosis with IgG3 (p=0.023) and IgG to NANP (p=0.023).

Induction of functional antibodies is highly variable and negatively influenced by malaria exposure

Responses were highly heterogenous among children, and the magnitude of neutrophil phagocytosis by antibodies was relatively modest, which may reflect modest vaccine efficacy. Interestingly, induction of functional antibodies was lower among children who had experienced higher malaria exposure. The basis for this negative influence is not known, but could reflect impacts of malaria on the innate immune system or CD4+ T-cells, which are important for vaccine responses. This contrasts to what is seen with COVID-19 vaccines where prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 is associated with better vaccine responses.

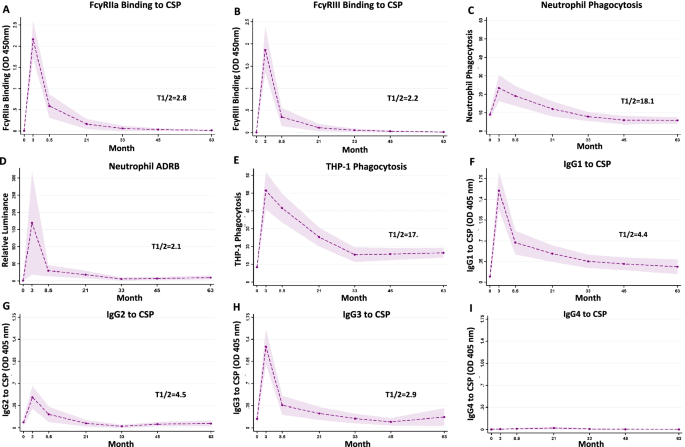

Protective immune responses are relatively short-lived

There is very limited data on the longevity of functional antibodies after vaccination with RTS,S. We found that functional antibodies largely declined within a year post-vaccination, and decay was highest in the first 6 months, consistent with the decline in vaccine efficacy over that time. Decay rates varied for different antibody parameters. Interestingly, decay was slower for neutrophil phagocytosis. This may be because the sensitivity of neutrophil phagocytosis to FcγR engagement by IgG means that there is a lower IgG threshold concentration required for activity, which may partly be explained by the expression of three activating FcγRs (FcγRIIIa, IIIb, and IIa) on the neutrophil surface.

Figure Legend: Serum samples were collected at baseline (month 0, M0), 30 days after the third vaccination (month 3, M3) and later time points (M8.5, M21, M33, M45 and M63). Samples were tested for A FcγRIIa-binding and B FcγRIII-binding to CSP, C opsonic phagocytis by neutrophils and D antibody-dependent respiratory burst (ADRB) in neutrophils and E opsonic phagocytosis by THP-1 cells. Antibodies were also tested for IgG subclasses to CSP, including F IgG1, G IgG2, H IgG3 and I IgG4. Data from immunologic assays were analysed in generalised linear mixed model (GLMM). The dashed lines represent the predicted means, the shaded area represents the 95% CIs and T1/2 (in months) indicates the estimated half-lives from the generalised linear mixed model. Half-life represents the time for magnitude to reduce by 50% from the M3 time-point.

Conclusions

Achieving high vaccine efficacy and greater longevity of efficacy are key global goals outlined by WHO and funding partners. We established key functional antibody activities induced by RTS,S, and the temporal kinetics of these responses, in young African children, who are the primary target group of the vaccine. Our results provide insights to understand the modest and time-limited efficacy of RTS,S in children. In future studies, analysis of these functional antibodies needs to be extended into the RTS,S phase III trial, including evaluation of responses in different populations, and an analysis of correlations of protection. Findings from this study address knowledge gaps around RTS,S immunity and may contribute to improving RTS,S efficacy and longevity in the future or the development of next-generation vaccines.

Link to the paper:

https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-022-02466-2

Feng G, Kurtovic L, Agius PA, Aitken EH, Sacarlal J, Wines BD, Hogarth PM, Rogerson SJ, Fowkes FJI, Dobaño C, Beeson JG. Induction, decay, and determinants of functional antibodies following vaccination with the RTS,S malaria vaccine in young children. BMC Med. 2022 Aug 25;20(1):289

Link to a related paper - Induction and decay of functional complement-fixing antibodies by the RTS,S malaria vaccine in children, and a negative impact of malaria exposure

https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-019-1277-x

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Medicine

This journal publishes outstanding and influential research in all areas of clinical practice, translational medicine, medical and health advances, public health, global health, policy, and general topics of interest to the biomedical and sociomedical professional communities.

Ask the Editor - Immunology, Pathogenesis, Inflammation and Innate Immunity

Got a question for the editor about the complement system in health and disease? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Weight loss interventions and their health impacts

BMC Medicine is calling for submissions to our new Collection on weight loss interventions and their health impacts, emphasizing a variety of strategies, including dietary changes, physical activity, pharmacological treatments, and surgical options. We encourage submissions that explore the long-term effects of these interventions, adherence challenges, and strategies to address health inequities. The goal is to advance understanding and improve outcomes in weight management and overall health.

Weight loss interventions encompass a wide range of strategies aimed at reducing body weight and improving health outcomes. These interventions can include dietary changes, increased physical activity, pharmacological treatments, and surgical options such as bariatric surgery. As the global prevalence of obesity and related comorbidities continues to rise, understanding the efficacy and mechanisms of various weight loss interventions becomes increasingly crucial for public health. This Collection seeks to explore the diverse methodologies and outcomes associated with weight loss interventions, offering insights into their impacts on both individual and population health.

The significance of this research is underscored by the growing body of evidence linking obesity to numerous chronic health conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and certain types of cancer. Advances in pharmacological treatments, such as SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists, have emerged as promising options for weight management, demonstrating not only weight loss but also improved metabolic health. There are, however, challenges and limitations related to drug availability, healthcare delivery, and long-term treatment adherence with rapid weight gain when stopping treatment. Additionally, integrating behavioral strategies with nutritional and physical activity interventions has shown potential in enhancing adherence and long-term success. By further investigating these modalities, we can develop comprehensive approaches that address the multifactorial nature of obesity.

Continued research in this domain may yield innovative strategies that harness technology, such as mobile health applications and telehealth, to support weight loss interventions. As we deepen our understanding of the genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors influencing obesity, personalized interventions tailored to individual needs could emerge. This progress may lead to improved health outcomes, reduced health inequities, and ultimately a shift in the paradigm of obesity treatment and prevention.

We are looking for original manuscripts on topics including, but not limited to:

•Clinical trials investigating interventions for weight loss to promote health

•Real-world data on long-term effects and challenges of weight loss interventions

•Factors affecting long-term adherence to weight-loss or weight maintenance interventions

•Challenges and inequities in access to weight loss interventions

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 07, 2026

Palliative care and medicine

BMC Medicine is calling for submissions to our new Collection, Palliative care and medicine, focused on the growing body of knowledge in end-of-life care. Palliative care is an essential component of healthcare that focuses on improving the quality of life for patients with serious, life-limiting illnesses. This specialized approach addresses not only physical symptoms but also psychological and social needs, emphasizing a holistic perspective on patient care. As the global population ages and the prevalence of chronic conditions rises, the demand for effective palliative care services is more critical than ever. This Collection aims to gather research that explores innovative practices, challenges, and advances in palliative care.

Advances in this field of palliative care have led to improved pain and symptom management techniques, enhanced communication strategies, and the integration of these initiatives into standard treatment protocols for various diseases. Additionally, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of advance care planning and bereavement support, which are crucial for ensuring that patients and their communities receive comprehensive care aligned with their values and preferences.

As research in palliative care continues to evolve, we may see the emergence of innovative models of care that integrate technology, such as telehealth solutions, to expand access and enhance patient engagement. Future studies may also focus on the development of personalized care plans that address the unique needs of diverse populations, ensuring that palliative care is equitable and inclusive. This ongoing exploration has the potential to transform the landscape of end-of-life care, ultimately improving the quality of life for patients and their communities.

Topics of interest include but are not limited to:

•Innovations in pain management in palliative care

•Advance care planning and its impact on quality of life

•Novel models for palliative and hospice care

•Bereavement support for families

•Addressing frailty in geriatric palliative care

•Palliative care in low-income and middle-income countries

•New technologies and big data for palliative care

•Access to palliative care medications

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 07, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in