Alveolar dendritic cell–T cell immunity hubs defending against pulmonary infection

Published in Immunology

It is well accepted that, when infection occurs, it takes one week or more for launching T cell response against a previously unseen pathogen. However, such dogma is built from the traditional experiments detecting immune responses. With the rapid development and application of in situ, high-throughput, single-cell spatial biotechnologies, new findings arise and such dogma needs to be revisited.

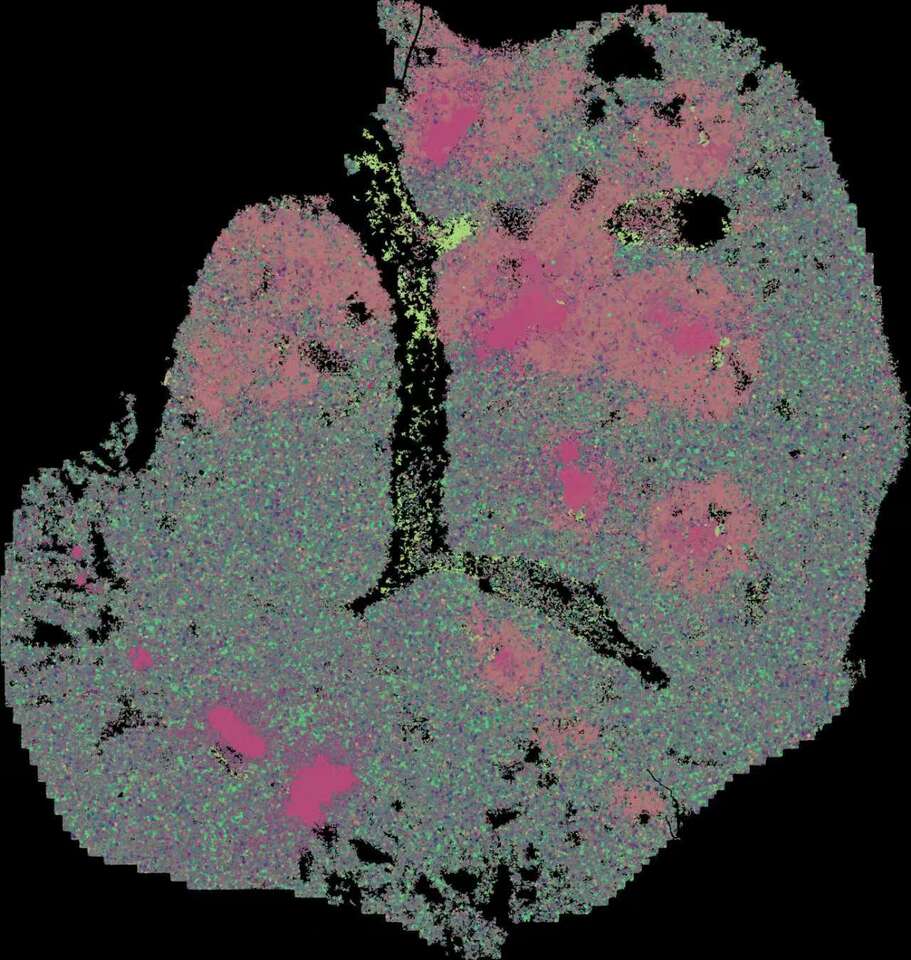

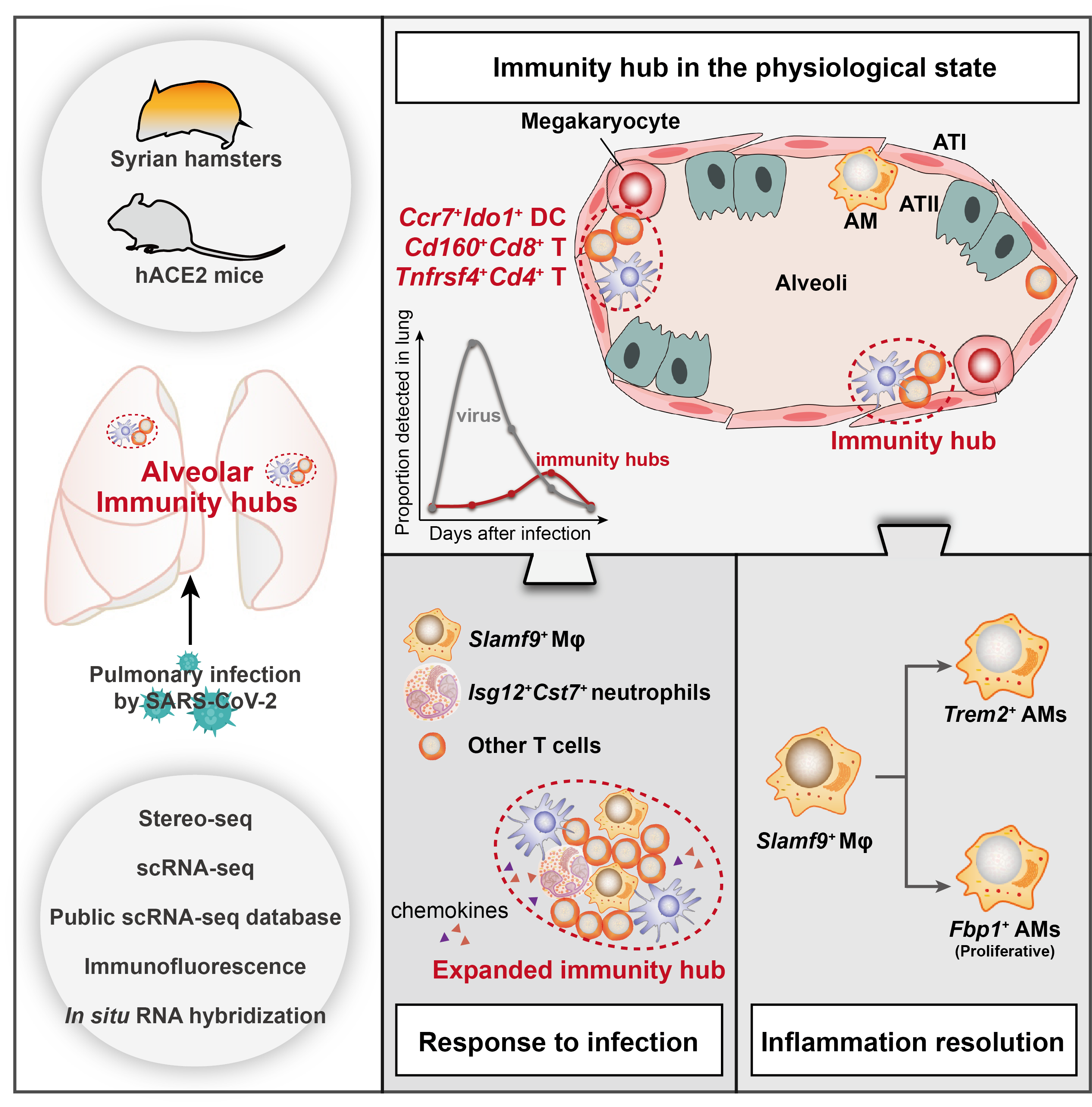

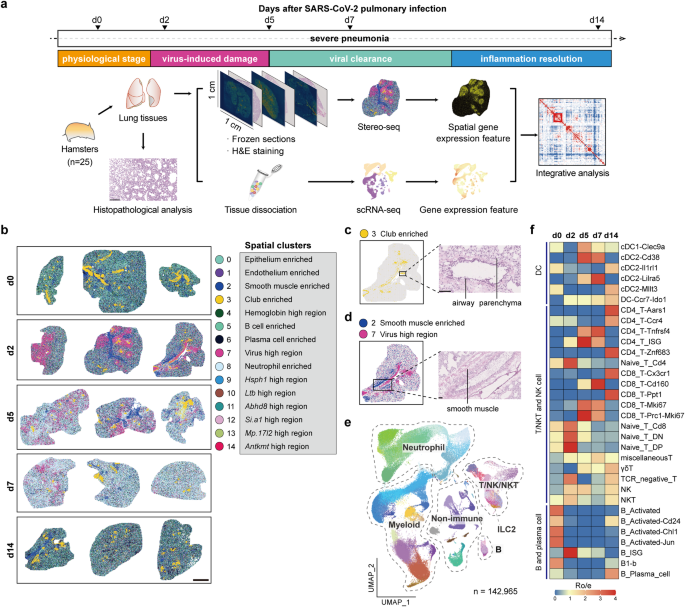

In our two companion studies recently published in Cell Discovery, we used SARS-CoV-2-infected Syrian hamsters as a model to investigate the whole process of pulmonary immune homeostasis from physiological condition, viral infection, viral clearance, to inflammation resolution. We applied an immunocartography technique that integrates spatial and single-cell transcriptomic sequencing via single-cell deconvolution and co-localization analysis. By charting the spatiotemporal distribution of immune cells across hamster lungs at single-cell resolution, we discover spatially co-localized dendritic cell (DC)-T cell immunity hubs in the alveolar regions, which play pivotal roles in responding and clearing SARS-CoV-2 infection. These DC-T immunity hubs are mainly composed of spatially co-localized Ccr7+Ido1+ dendritic cells, Cd160+Cd8+ T cells, and Tnfrsf4+Cd4+ T cells, which reside in the alveoli under physiological conditions at a low level (lower than 1%). Both the number and the size of DC-T immunity hubs rapidly increase at least as early as 2 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

We find that multiple myeloid cell types, including macrophages, DCs and neutrophils, are enriched in DC-T immunity hubs at 5 to 7 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially a subpopulation of Slamf9+ macrophages. Therefore, we further analyzed the specific characteristics and the potential function of these Slamf9+ macrophages. We found that Slamf9+ macrophages may engulf SARS-CoV-2 and are resistant to cell deaths caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection because of the extremely high rates of SARS-CoV-2 RNA positivity and the significant expansion after SARS-CoV-2 infection, different from those tissue-resident alveolar macrophages. Besides, these macrophages might also secrete chemokines to recruit neutrophils, which is also involved in the function of DC-T immunity hubs, to clear SARS-CoV-2 together, and secrete IL-10 to induce an immunosuppressive niche that is co-localized by Isg12+Cst7+ neutrophils to prevent infection-induced injury. After viral clearance, Slamf9+ macrophages differentiate into Trem2+ and Fbp1+ macrophages and promote inflammation resolution, alveolar macrophage replenishment and tissue repair. Meanwhile, the DC-T immunity hubs decrease and restore to the physiological levels at about two weeks after infection.

Collectively, our study suggests that DC-T immunity hubs, together with Slamf9+ macrophages, function at the core of pulmonary immune surveillance by participating viral containment, viral clearance, and inflammation resolution. Experimental validations in hamsters, mice (and hACE2 transgenic mice), and human samples prove the wide presence of such DC-T immunity hubs in alveoli and their protective roles against infection and even cancer.

A paper recently published in Nature Immunology also described a similar finding, strengthening the biological significance of DC-T immunity hubs. Chen et al. found that CCR7+ DCs, TCF7+PD-1+ progenitor CD8+ T cells, CXCL10/CXCL11+ macrophages and CCL19+ fibroblasts constitute stem-like immunity hubs, which are associated with immunotherapy responsiveness in human lung tumors1. This finding further enhances our findings about DC-T immunity hubs in the lung, and strengthened their function in not only pulmonary infection, but also in tumor immunology and immunotherapy.

Considering the occurrence of age-related changes in multiple cell types in the lung2, and the profound differences in immune responses and disease susceptibility between males and females through the regulation of DC homeostasis3, it is still an open question whether the function of DC-T immunity hubs is affected by age- or gender-related changes. Besides, other types of multi-cellular communities in different tissues may play important roles far beyond current understanding, which needs deeper investigation. Collectively, our findings provide new insights to the early function of T cells against infection and the host immune defense mechanisms in the lung. The techniques we employ represent a paradigm-shifting transformation to immunological and infectious studies.

You can find more details of our two companion papers in Cell Discovery (doi.org/10.1038/s41421-024-00733-5 and doi.org/10.1038/s41421-024-00734-4).

Schematic diagram

DC-T immunity hubs were physiologically detected in hamster lungs, which were mainly composed of spatially co-localized Cd160+Cd8+ T cells, Tnfrsf4+Cd4+ T cells and Ccr7+Ido1+ DCs. After SARS-CoV-2 infection, the immunity hubs expanded by recruiting Slamf9+ macrophages and Isg12+Cst7+ neutrophils to jointly clear viral infection. After viral clearance, the immunity hubs restored to physiological levels, and Slamf9+ macrophages may differentiate into Fbp1+ and Trem2+ macrophages, promoting inflammation resolution.

References

1 Chen, J. H. et al. Human lung cancer harbors spatially organized stem-immunity hubs associated with response to immunotherapy. Nat Immunol 25, 644-658, doi:10.1038/s41590-024-01792-2 (2024).

2 Cho, S. J. & Stout-Delgado, H. W. Aging and Lung Disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 82, 433-459, doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-021119-034610 (2020).

3 Chi, L. et al. Sexual dimorphism in skin immunity is mediated by an androgen-ILC2-dendritic cell axis. Science 384, eadk6200, doi:10.1126/science.adk6200 (2024).

Follow the Topic

-

Cell Discovery

This journal aims to provide an open access platform for scientists to publish their outstanding original works and publishes results of high significance and broad interest in all areas of molecular and cell biology.

Ask the Editor - Immunology, Pathogenesis, Inflammation and Innate Immunity

Got a question for the editor about the complement system in health and disease? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in