Ancient DNA from 300,000-year-old horses

Published in Ecology & Evolution

A Jurassic Park reality check

The term deep-time palaeogenomics may bring to mind Jurassic Park, where dinosaurs are brought back to life. Luckily, that’s not on the horizon. Dinosaurs went extinct around 65 million years ago, and the oldest DNA ever recovered from a bone belongs to a mammoth about a million years old.

Recently, headlines about biotech efforts to “bring back” dire wolves have captured people's imagination, curiosity, and concern. But beyond the pop culture hype, what does it really mean to study ancient DNA from extinct animals? And why should we care today?

The challenge of ancient DNA

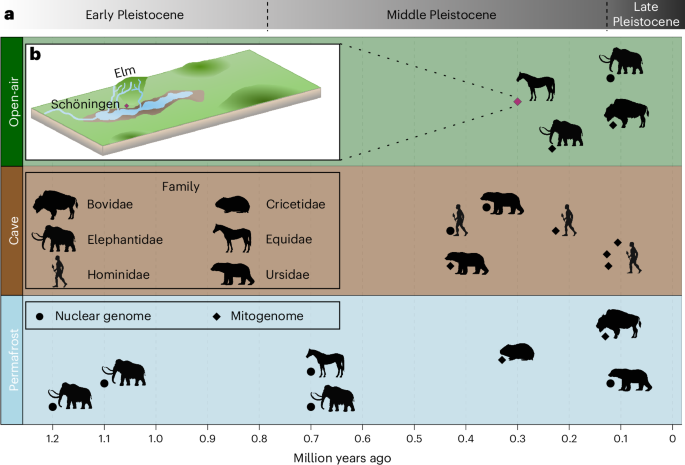

The further back we look in time, the less likely DNA is to survive. Preservation depends on temperature and environment, among other factors. Permafrost is best, acting like a natural freezer. Caves, with their stable climates, come next. Open-air sites are the most challenging, since weather and disturbance accelerate decay.

That’s why expectations were low when Arianna Weingarten, then a Master’s student, requested samples from horse bones excavated from Schöningen, a 300,000-year-old open-air site in Germany. Fortunately, her supervisor, Professor Nicholas J. Conard and Dr. Jordi Serangeli, the Schöningen excavation leader, readily agreed. Schöningen is famous in the field of prehistoric archaeology for its wooden spears, the oldest complete weapons ever found, lying alongside the remains of 20-25 butchered horses. This discovery reshaped our understanding of early humans, showing that either late Homo heidelbergensis or early Neanderthals could plan and coordinate hunts instead of scavenging from other predators.

Once a paleolake, Schöningen has yielded more than 20,000 large mammal remains, making it a key reference site for the central European interglacial faunal record. Yet, despite its excellent preservation, no ancient DNA had ever been successfully retrieved from the site.

A risky master’s thesis

Arianna sampled dense horse petrous bones, the skull’s inner ear region, which was shown to better preserve DNA, at the Max Planck Institute in Jena. “Let’s see, you never know until you try,” said the lab technician Rita Radzeviciute, training her, as they worked through the charcoal black bones. After a long day of drilling, they left with sore wrists and little hope of success.

.jpg)

Back in the lab, the bone powder was processed with methods designed to capture the short, degraded DNA fragments expected from such old samples. When the sequences were compared against a modern horse genome, Arianna was stunned: the experiment had worked. Ancient DNA had survived at Schöningen. This finding pushed the known age limit for open-air DNA preservation back by 60,000 years and set the groundwork for her PhD.

From butcher shop to breakthrough

Arianna’s Master’s thesis showed the project was technically possible. The next step was to recover more meaningful evolutionary information. Guided by her supervisor Professor Cosimo Posth, they focused on the mitochondrial genome, a small, maternally inherited part of DNA that is easier to recover from degraded samples.

In order to “fish-out” the mitochondrial regions of the ancient samples, the first step was to create baits for a capture experiment. They soon found that they would need modern horse DNA for realising this capture experiment, which resulted in a trip to a horse butcher near Tübingen. After an awkward exchange in broken German, she had secured a piece of horse meat. Back in the lab, DNA was extracted, amplified, sheared, and prepared for the capture experiment. A few months later, the results were in: the team had the mitochondrial genomes of the Schöningen horses!

Another risky master’s thesis: building better tools

Ancient DNA is fragile and full of chemical damage. Reconstructing accurate genomes required a new bioinformatics approach. That’s when Meret Häusler, a bioinformatics master’s student in her final semester, joined the project. With no prior experience in ancient DNA but a research interest in evolution, she quickly immersed herself in the challenges of damaged data. Six months later, after many setbacks, hair-pulling and finally some breakthroughs, she had developed a new method, together with her supervisor Kay Nieselt, to reconstruct genomes without discarding valuable information or relying too heavily on modern references.

This method down-weights damaged bases while giving more weight to intact ones, recovering authentic sequences from low-coverage, degraded samples like the Schöningen horses. This turned out to be essential to better understand their evolutionary story.

Uncovering a lost lineage of horses

By reconstructing near-complete mitochondrial genomes, the team could finally place the Schöningen horses within the broader evolutionary history of Equus. Most published ancient horse genomes date to around 50,000 years ago or younger, reflecting the research focus on domestication. Only one genome older than Schöningen has ever been published: a ~670,000-year-old horse bone discovered in permafrost in the Yukon territory of North America.

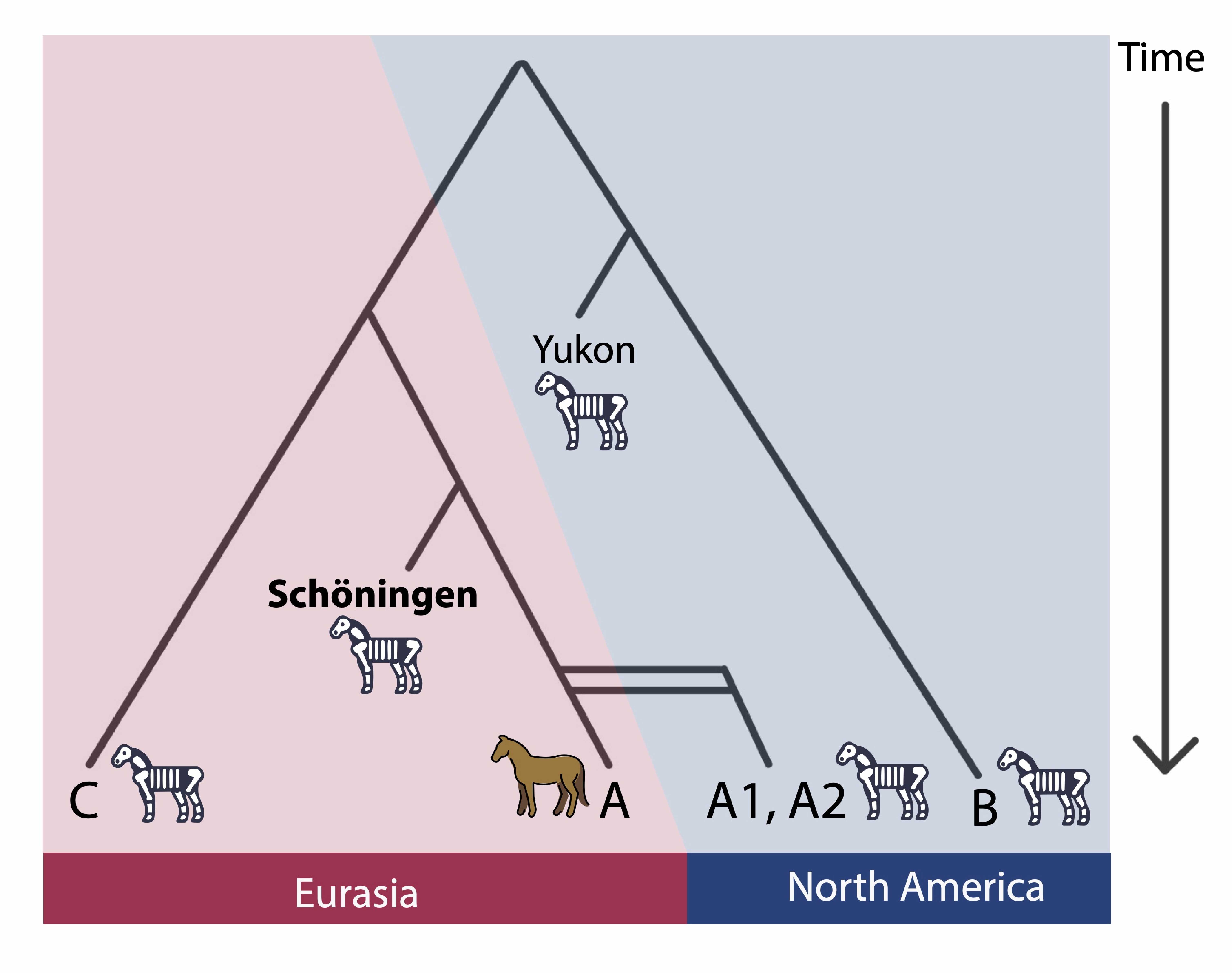

Placed in this framework, the Schöningen genomes proved exceptional. They sit at the base of clade A, the maternal lineage that includes all living horses (E. caballus, E. ferus, and E. przewalskii). This revealed a previously unknown, deeply divergent branch of horse evolution.

Horse mitochondrial DNA tree showing the Schöningen horses positioned at the base of clade A. The clades are phylogeographically structured between Eurasia and North America, with migrations occurring across the Bering Land Bridge during favorable climatic periods. The skeleton horses represent extinct clades, while the brown horse represents the sole surviving mitochondrial clade today (Graphic: Arianna Weingarten).

Molecular dating showed that the Schöningen lineage split from other horses about 570,000 years ago, predating the diversification within clade A and pointing to a common ancestor of Schöningen and modern horses. The genomes themselves were dated to ~360,000 years ago, aligning with the older archaeological chronology for the Schöningen Spear Horizon.

This discovery extends the limits of DNA preservation in open-air sites and deepens our understanding of horse evolution in the Middle Pleistocene. It also provides a new bioinformatic tool and paves the way for future collaborations between archaeology, bioinformatics, and palaeogenetics. The past still holds many unknown worlds to discover, even without bringing back dinosaurs!

To find out more, read our open access paper entitled "Mitochondrial genomes of Middle Pleistocene horses from the open-air site complex of Schöningen"published in Nature Ecology & Evolution on October 1st, 2025.

Many thanks to Cosimo Posth, Guido Gnecchi-Ruscone and Ivo Verheijen for their comments on this blog post and to all other co-authors for their support throughout this study.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in