Antimicrobial exposure is associated with decreased survival in triple-negative breast cancer

Published in Cancer

Background

Studying the impact of antimicrobial exposure during cancer treatment on survival.

For nearly a decade, studies have shown that the gut microbiome can influence cancer outcomes by modulating host immunity, regulating the tumor microbiome and microenvironment1-4. Because the specific microorganisms that are associated with therapy responsiveness vary across these studies5 and because studies of the long-term impact on survival are lacking, these observations have left doctors and patients uncertain about how to make decisions during care that may alter the gut microbiome—specifically, prescriptions for antibiotics and antifungals to treat infections.

To address this gap, we leveraged extensive, long-term electronic health record data and the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry to determine whether antimicrobial exposure is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with curable triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). We chose to focus on TNBC because it is the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer6 and disproportionately affects minoritized women of African American race and Hispanic ethnicity7. It also has much more limited treatment options compared to HER2-positive or hormone receptor-positive breast cancers, and appears to be highly modulated by the immune system, which is thought to be shaped by the microbiome.

We previously showed that lower absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) after TNBC diagnosis was associated with worse survival8, but it was unclear what might be leading to lower ALC counts. Here, we hypothesized that greater exposure to antibiotics and antifungals might disrupt the gut microbiome, in turn leading to decreased circulating lymphocytes and worse survival after breast cancer diagnosis. We developed a statistical model incorporating the known relationship of ALC and TNBC survival to study the relationship between antimicrobial exposure and TNBC survival.

Key Findings

Antimicrobial exposure is adversely associated with survival from breast cancer.

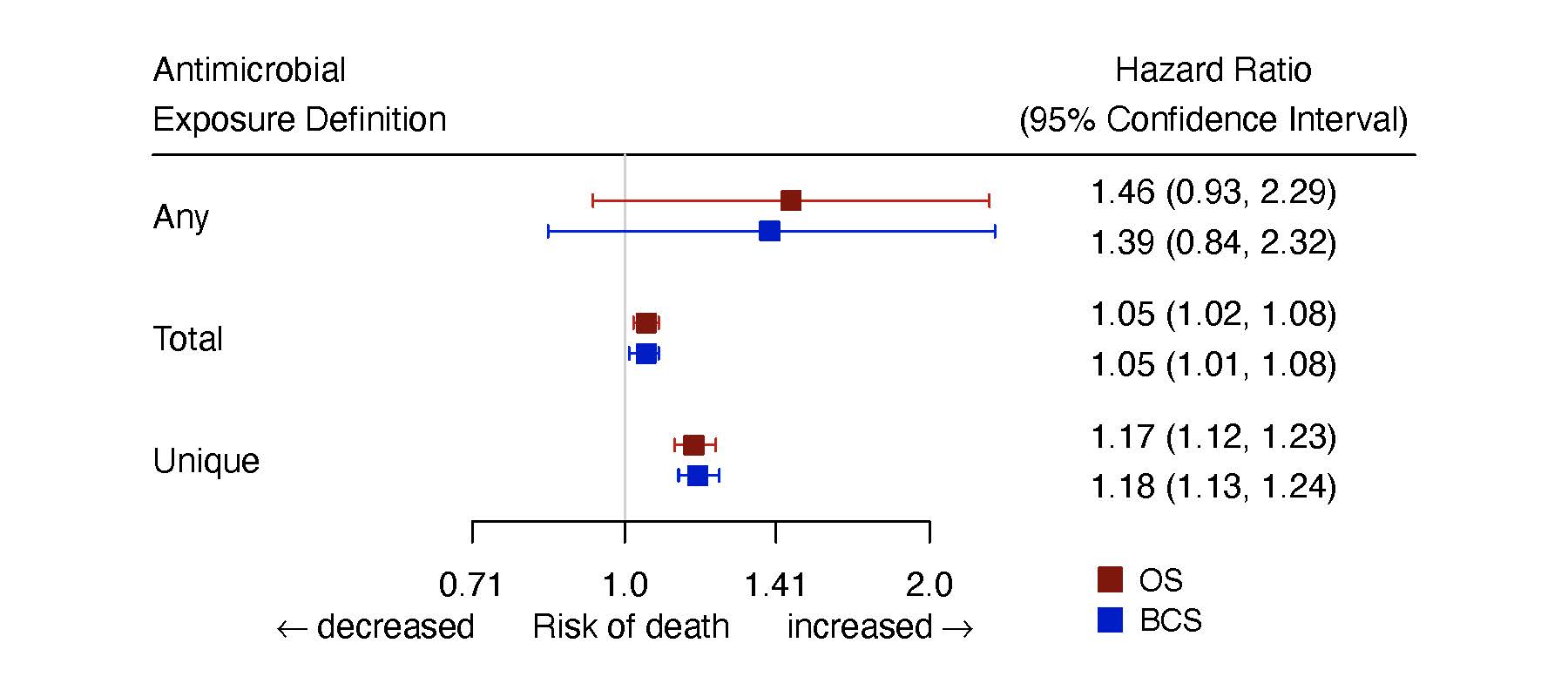

We defined exposure to antimicrobials in three different ways. “Any” exposure was defined as a patient receiving one or more antimicrobial drugs after TNBC diagnosis. “Total” exposure was defined as the total number of antimicrobial prescriptions at each point in time, and “unique” exposure was defined as the total number of unique antimicrobial prescriptions at each point in time—that is, not counting multiple prescriptions for the same medication. We aimed to study both the breadth and depth of exposures, which could impact the gut microbiome differently. In controlled, multivariate analysis we found that each additional total or unique antimicrobial prescription increased the risk of both overall and breast cancer-specific mortality by between 5 and 18%, and that this association was related to changes in lymphocyte counts (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for any, total, and unique antimicrobial exposures in the multivariate model.

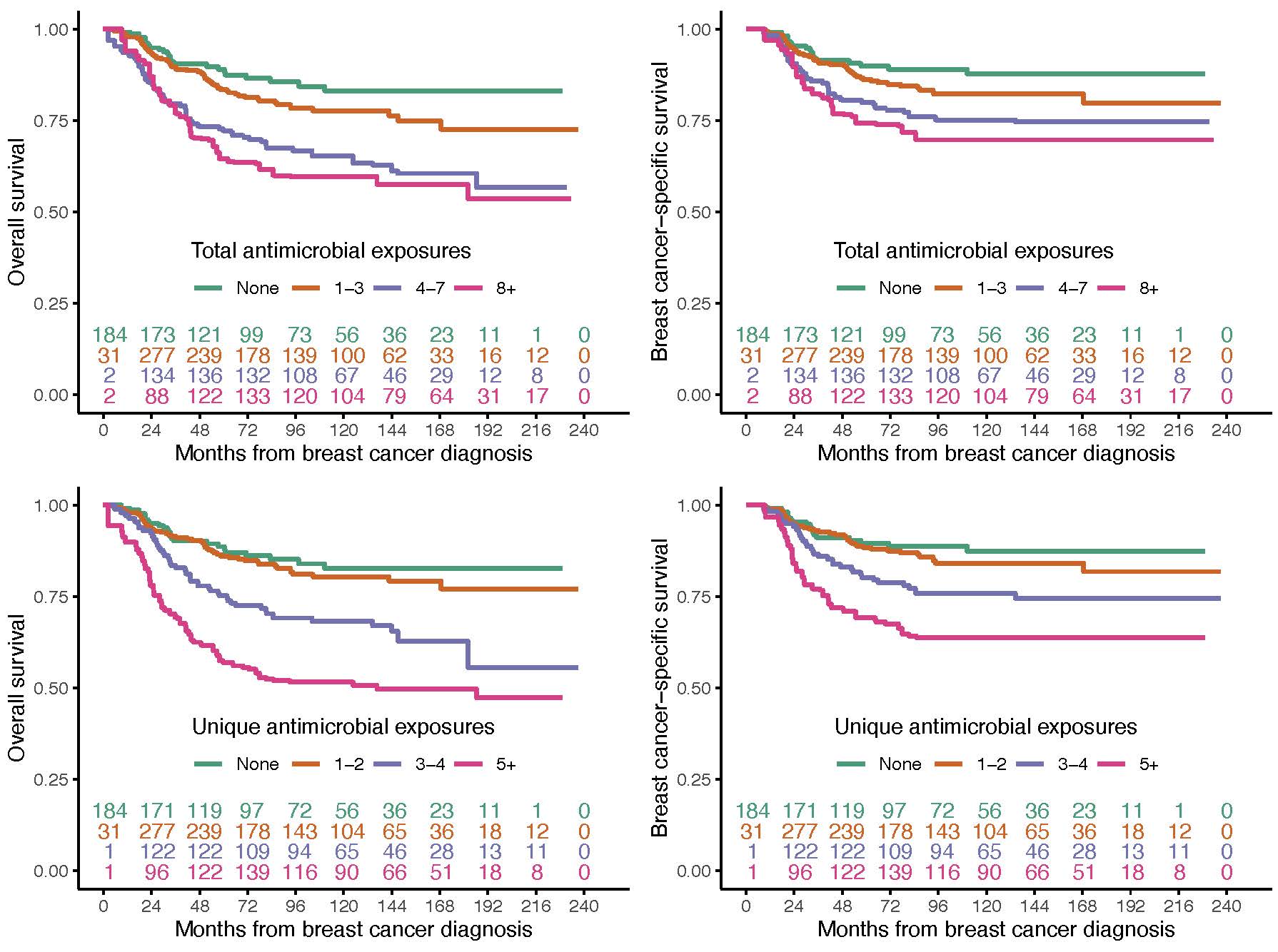

We additionally showed that an increasing number of antimicrobial prescriptions was associated with worse overall and breast cancer-specific survival (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Estimates of overall (left) and breast cancer-specific (right) survival for the total and unique number of antimicrobial prescriptions. The inset numbers are the number of patients at risk of death at each point in time.

Worse survival cannot be explained by sicker patients receiving more prescriptions.

Because patients who are sicker at the time of cancer diagnosis may be more likely to develop infections, have lower blood counts, and be prescribed antibiotics, we also controlled the statistical analyses for indicators of severe illness, to see if this would decrease the strength of the association between antimicrobial exposure and survival. We did not see a significant change in the association between antimicrobial exposures and survival, offering evidence that it is not explained by sicker patients receiving more antimicrobials. Because chemotherapy can lower all blood counts, we also looked at whether the observed survival association was related to neutrophil counts, since neutrophils help fight infections but are not known to be related to tumor-directed immunity. There was no association between neutrophil counts and survival, suggesting that the findings are specifically related to lymphocyte counts. These findings lend support to the theory that cumulative antimicrobial exposure disrupts the gut microbiome and ultimately impairs lymphocyte-mediated antitumor immunity.

Antimicrobial exposure is associated with impaired survival for three years following diagnosis.

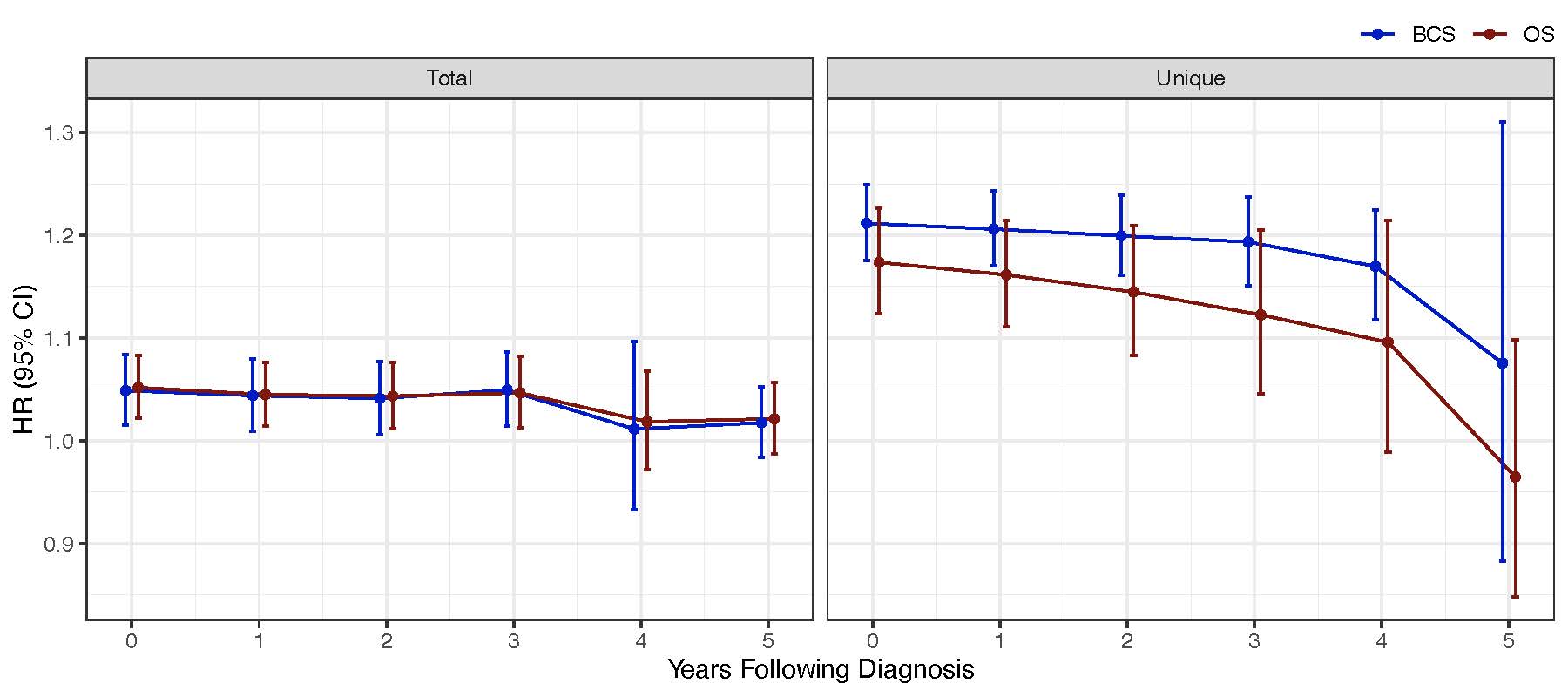

Since patients with curable TNBC complete their treatment within a year of diagnosis but remain at high risk of cancer recurrence for up to five years, we also looked at how antimicrobials given during this five-year period impact survival. For both the “total” and “unique” exposure definitions, we found that patients who continued to receive antimicrobials had a persistently increased risk of death for three years, which tapered off by year five (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The impact of antimicrobial exposure on survival over time. HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; OS: overall survival; BCS: breast cancer-specific survival.

Take-Home Message

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association of antimicrobial exposure during treatment with breast cancer survival. It contributes to increasing evidence that immune dysregulation during cancer treatment and follow-up influences survival outcomes and may be generalizable to other cancers. These results are particularly timely for clinical practice, given the progressive incorporation of immune checkpoint inhibitors into most solid tumor treatment algorithms including that of TNBC, and suggest that the number and range of antimicrobials prescribed should be carefully considered. We anticipate this study will serve as motivation for further investigations aimed at understanding the relationship between antimicrobial exposure and cancer survival.

References

- Sepich-Poore, G.D., et al. The microbiome and human cancer. Science 371(2021).

- Gopalakrishnan, V., et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 359, 97-103 (2018).

- Matson, V., et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 359, 104-108 (2018).

- Routy, B., et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 359, 91-97 (2018).

- Lee, K.A., et al. Cross-cohort gut microbiome associations with immune checkpoint inhibitor response in advanced melanoma. Nat Med 28, 535-544 (2022).

- Foulkes, W.D., Smith, I.E. & Reis-Filho, J.S. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 363, 1938-1948 (2010).

- Hudis, C.A. & Gianni, L. Triple-negative breast cancer: an unmet medical need. Oncologist 16 Suppl 1, 1-11 (2011).

- Afghahi, A., et al. Higher Absolute Lymphocyte Counts Predict Lower Mortality from Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 24, 2851-2858 (2018).

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in