Are sex and gender adequately considered in head and neck cancer clinical studies?

Published in Sustainability and Biomedical Research

.jpg) Analyses of data from US cancer registries highlighted significant differences in terms of cancer incidence and mortality between men and women in some cancer types –which cannot be fully explained by differences in behavior and environmental exposure–, as well as differences in therapy-related toxicity. Indeed, studies revealed an overall higher risk of severe adverse events upon anticancer treatment in women as compared to men (1). Such differences were particularly significant for patients receiving immunotherapy. Recent research efforts revealed that in colorectal cancer, KDM5D gene –which is located on the Y chromosome– is a major cause of the worse clinical outcome of male colorectal cancer patients, offering a potential novel therapeutic target (2). Similarly, bladder tumors lacking the Y chromosome display a more aggressive behavior as compared to those having the Y chromosome, likely due to a CD8 T cell dysfunction in the tumor microenvironment (3). Furthermore, it has been shown that the gut microbiota antagonizes the development of colorectal cancer in a sex-specific manner, through estrogen-mediated increased colonization of the female gut by specific bacterial species improving gut barrier integrity and reducing inflammation (4). Despite the increasing mechanistic evidence of sex-based differences on human physiopathology, many studies still combine together male and female results.

Analyses of data from US cancer registries highlighted significant differences in terms of cancer incidence and mortality between men and women in some cancer types –which cannot be fully explained by differences in behavior and environmental exposure–, as well as differences in therapy-related toxicity. Indeed, studies revealed an overall higher risk of severe adverse events upon anticancer treatment in women as compared to men (1). Such differences were particularly significant for patients receiving immunotherapy. Recent research efforts revealed that in colorectal cancer, KDM5D gene –which is located on the Y chromosome– is a major cause of the worse clinical outcome of male colorectal cancer patients, offering a potential novel therapeutic target (2). Similarly, bladder tumors lacking the Y chromosome display a more aggressive behavior as compared to those having the Y chromosome, likely due to a CD8 T cell dysfunction in the tumor microenvironment (3). Furthermore, it has been shown that the gut microbiota antagonizes the development of colorectal cancer in a sex-specific manner, through estrogen-mediated increased colonization of the female gut by specific bacterial species improving gut barrier integrity and reducing inflammation (4). Despite the increasing mechanistic evidence of sex-based differences on human physiopathology, many studies still combine together male and female results.

Previous studies reported that head and neck cancer is significantly more frequent in men than in women (5). The underlying reasons for such differences are currently unknown (6); however, they indicate the need for including these variables for more accurate, unbiased analyses of scientific results as well as for an adequate approach to patient care.

In our paper, we analyzed to what extent sex and gender variables are currently considered in head and neck cancer clinical research.

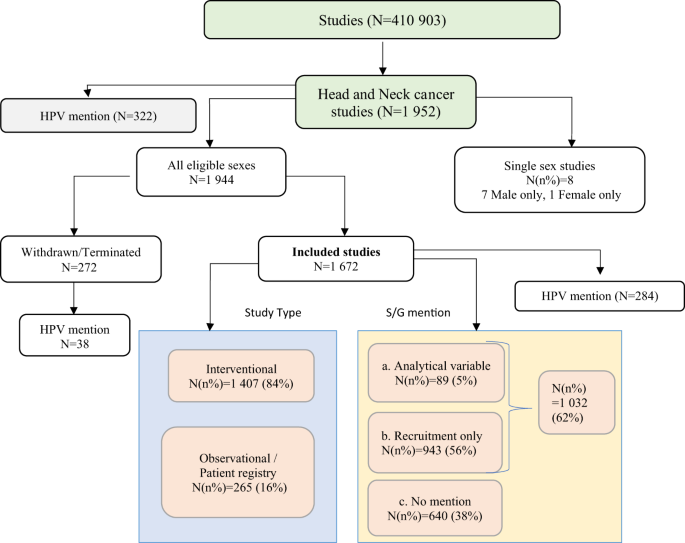

We searched head and neck cancer clinical studies registered on clinicaltrial.gov –the largest universally accepted registry of FDA-recognized clinical trials– from 1999 to 2022 which considered sex and gender as variables to be analyzed. Although sex and gender are not synonymous, our analysis considered both factors indistinctly, considering sex as a proxy for gender (the latter one is more strictly related to other potentially confounding factors related to lifestyle and behavior and thus a more difficult variable to take into account)(7,8). Our results were then validated by analyzing the corresponding studies published in scientific journals considering sex or gender in the analysis.

Our study provides a snapshot of the current situation regarding the inclusion of sex and gender in clinical research. Specifically, our results highlighted that, despite the increasing awareness about the importance of taking into consideration sex/gender differences as much as other biological variables, which has remarkably increased over the past ten years (9), sex and gender variables are currently largely overlooked in head and neck cancer clinical studies, where they represent, instead, a critical variable, significantly influencing cancer incidence. As few as 5% of the clinical studies consider sex/gender as an actual variable to be analyzed, more frequently in large patient cohorts (sufficiently large to be subdivided in subgroups) and in observational studies than in small patient cohorts and in interventional studies.

Since 1994 USA has imposed the inclusion of women in clinical trials as well as the conduction of sex-based subgroup analyses on study results (10). As a consequence, medical and research centres showed a greater inclusion of sex as an analytical variable (11) also in head and neck studies, in which the effect on disease outcome can be significant (12). However, our work strongly indicates that a further effort is needed to increase awareness within the scientific community about the importance of a sex and gender-weighted research. Taking into consideration such factors as much as other sociodemographic variables in cancer study design would contribute to build a more inclusive healthcare system and foster personalised medicine, as medical evidence from clinical and scientific research studies will no longer derive from biased analyses.

References:

1) Unger et al., Sex Differences in Risk of Severe Adverse Events in Patients Receiving Immunotherapy, Targeted Therapy, or Chemotherapy in Cancer Clinical Trials. JCO 13, 1474–1486 (2022)

2) Li et al., Histone demethylase KDM5D upregulation drives sex differences in colon cancer. Nature 619, 632-639 (2023)

3) Abdel-Hafiz et al., Y chromosome loss in cancer drives growth by evasion of adaptive immunity. Nature 619, 624-631 (2023).

4) Li et al., Carnobacterium maltaromaticum boosts intestinal vitamin D production to suppress colorectal cancer in female mice. Cancer cell 41, 1450-1465 (2023).

5) Windon, M. J. et al. Increasing prevalence of human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal

cancers among older adults. Cancer. 124, 2993–2999 (2018).

6) Chaturvedi, A. K., Freedman, N. D. & Abnet, C. C. The Evolving Epidemiology of Oral

Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancers. Cancer Res. 82, 2821–2823 (2022).

7) Lilian Hunt et al., A framework for sex, gender, and diversity analysis in research. Science 377, 1492-1495 (2022).

8) Irene Gottgens et al., Moving beyond gender identity: the need for contextualization in gender-sensitive medical research. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 24,100548 (2022).

9) Rubin, J. B. The spectrum of sex differences in cancer. Trends Cancer 8, 303–315 (2022).

10) History of Women’s Participation in Clinical Research | Office of Research on Women’s

Health. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/toolkit/recruitment/history.

11) Wagner, A. D. et al. Gender medicine and oncology: report and consensus of an ESMO

workshop. Annals of Oncology. 30, 1914–1924 (2019).

12) Mazul AL et al., Disparities in head and neck cancer incidence and trends by race/ethnicity and sex. Head Neck 45, 75-84. (2023).

Follow the Topic

-

npj Precision Oncology

An international, peer-reviewed journal committed to publishing cutting-edge scientific research in all aspects of precision oncology from basic science to translational applications to clinical medicine.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

AI Approaches in Drug Design

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Genomic Instability

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in