Are we getting it right? Community-based climate change adaptation in the Pacific

Published in Social Sciences

The initial project idea was driven by the question: ‘are we getting it right?’ With anthropogenic climate change now assured and accelerating, adaptation is an urgent part of our global response. For the Pacific Islands region, adaptation is particularly important given the sensitivity of the region to climate variability and extreme weather events.

The impacts of climate change in the Pacific are clear – with cyclones creating paths of destruction and sea levels rising – but we cannot be equally sure about the effectiveness of our responses. While well-intentioned donors and others rush to fund and support the implementation of adaptation initiatives at the local level, there has been limited reflection on their effectiveness to date. There remains a lot of uncertainty around whether communities are any better prepared to cope in the long-term.

It is from these concerns that this project idea was born: what has been the progress of community-based adaptation (CBA) efforts in the Pacific? What lessons do we need to take heed of to improve practice and ensure donor expenditure is used most effectively? Our three-year study, funded by the Australian Research Council, involved 415 participants in 20 rural communities in Fiji, Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati and Vanuatu. Thirty-two diverse CBA initiatives were evaluated drawing from focus groups and interviews. Our study has been published today in Nature Climate Change (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-020-0813-1).

Given the practical and applied nature of the research project, we collaborated with diverse project partners and experts that traversed humanitarian, development and environmental fields. We partnered with eight non-governmental organisations that have a long lineage of working at the community level in the Pacific. Capacity building was also a critical component of this project with a number of PhD and Honours students as well as local research assistants involved.

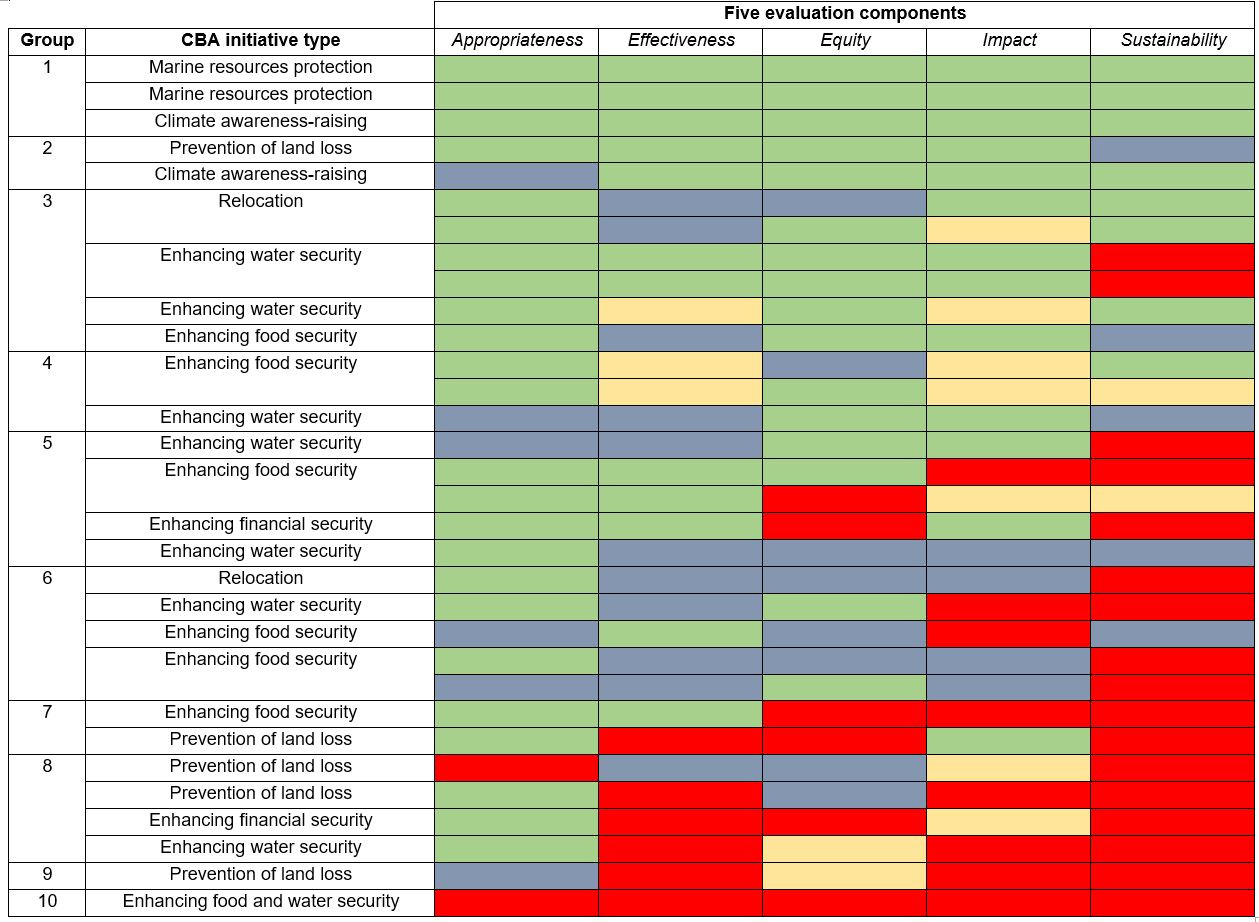

We found that CBA success is mixed (see Table 1 below). Although initiatives were often appropriate to local context, they struggled to be sustainable once funding ceased. Initiatives that integrated CBA with ecosystem-based adaptation or raised climate change awareness performed the best; while those focussed on preventing land loss from rising seas and coastal erosion generally performed less well.

We identified four key lessons for improvement. The first is to ensure local approval and ownership which will ensure that projects are well received and maintained. The second is to guarantee shared access to, and benefit from, initiatives so that new inequalities are not created, and existing ones are not worsened. The third is to ensure that initiatives are driven by local realities, including the community context, priorities, resources and knowledge. The fourth is to have a wider impact, especially in terms of reducing overall vulnerability (i.e. not just climatic) in a relevant system and having impact over longer timespans.

These lessons pivot around an overarching message that we need to move beyond merely ‘basing’ adaptation in communities, to adaptation that is led by them. As we write in our paper, communities should drive their own agendas based on local knowledge, experiences and coping mechanisms, while external actors should realign themselves as ‘facilitators’ for achieving local objectives equitably and effectively. Ultimately, the role of implementers and donors is to prepare and support communities to lead their own adaptation. Pacific communities have, after all, effectively coped with and adapted to disturbances and change for centuries. We hope our study contributes to a growing and credible evidence base from which good future CBA practice can be formed, and from which hope for the resilience of future communities can be found.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Climate Change

A monthly journal dedicated to publishing the most significant and cutting-edge research on the nature, underlying causes or impacts of global climate change and its implications for the economy, policy and the world at large.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in